The Australian director spoke with us about his wonderful documentary “Dyarubbin”, in competition at the Indiecinema Film Festival’s third edition!

On 3 October 2024, Michael Gill’s very interesting documentary, Dyarubbin, was screened at the Circolo Arci Arcobaleno in Rome together with The Korean from Seoul by Steven Paul Whatmough, during a special evening dedicated by Indiecinema Film Festival to the best indie movies from Australia.

On that occasion we started a stimulating and fruitful conversation by maill with the documentary maker. Here is the result.

People and landscapes of Spencer

First, Michael, how did the need to film a remote – and in some respects still wild – place like Spencer arise in you?

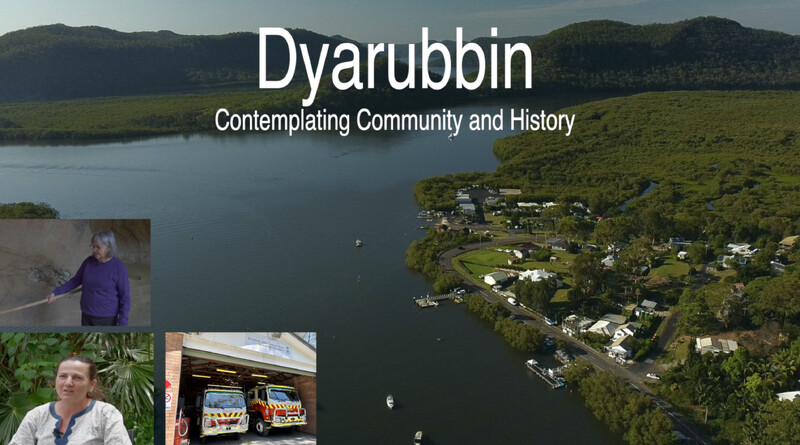

A serendipitous meeting with a person who told me about Spencer having a history of Aboriginal massacre during the early days of Australian settlement. We are talking about the period 1799 to about 1880. I travelled to Spencer and was impressed by the wonderful scenery and the place as two rivers meet there. Photographically the place was wonderful and the history was the basis for the initial script. Dyarubbin is the indigenous name used by the local tribe to mean ‘the meeting place of two rivers’.

How did your relationship with some of the Spencer residents, whom we see interviewed in the documentary, develop during the filming of Dyarubbin?

I spent around two months visiting Spencer regularly to establish a rapport with the locals and understand how the small town/village operated. My initial contact was with the Spencer Coffee Club members. I was then introduced to other residents of Spencer. Filming started in the third month after I had identified a small group of willing participants.

From the Aboriginal Question to interest in Nature

What struck you most, starting from the exciting visit to the cave, about the Aboriginal culture present in Spencer? And a title as “Dyarubbin” is linking tu such culture too?

Spencer is surrounded by high cliffs which contain over 3000 indigenous images, symbols and rock cavings, including one of a whale 25 metres long. Obtaining access and then climbing with camera gear is both complex and difficult. With over an hour of walking and climbing, I was eventually guided to the cave featured in the documentary. The cliffs contain minerals which at sunrise and sunset “light up” wand this required a boat with a steady cam mounted camera to shoot successfully.

In your film we see a very powerful, majestic and fascinating image of Nature, but we see practically no animals. Why weren’t they filmed??

The forests around Spencer are steep and dense with majestic trees and steep valleys. The birdlife is extensive and very active at dawn. There are many animals (mostly nocturnal) including kangaroos, snakes and possums to name a few. Trying to shoot at night was a task beyond my technical abilities and in any case, I did not want to be eaten by crawling insects.

The persecution of the Aborigines by the new arrivals, the settlers, is explained quite well in your documentary. Did you consult with any historians before shooting it? Or did you draw inspiration from films made by other directors, such as Rolf de Heer?

The informer featured in the video has a doctorate in indigenous history and was ideal of my purposes. I conducted extensive desk research about the local bloody history of Spencer and the wider location. I also visited the State Library in Sydney where I found anthropological texts detailing most of the 3,000 rock cave images. As regards Rolf de Heer, I watched his film Twelve Canoes and learnt about his treatment of landscape.

Firefighters and suggestive soundtrack

How did the relationship with the local firefighters develop? And does the sequence you filmed with them represent a real intervention or is it perhaps demonstrative, an exercise?

The local firefighter team were perhaps the hardest group to deal with as they are part of a state bureaucracy, so a good deal of paper work was required. I searched out the original families still living in Spencer and discovered that the captain was a ‘first family’ descendant. Waiting for a bushfire in a particular area is unproductive. As I only use my own video image material the team arranged a training session near Spencer. The training session was genuine and involved recent recruits. It was a privilege to be allowed to ride and film from inside the truck.

We found the soundtrack suggestive, with some more solemn songs and other music with a more “country” aftertaste. How did you choose and insert the music into the film?

Choosing music involved hours of listening to various potential selections from numerous websites. The music used in the documentary was my choice alone. I hold the necessary Commons license. In addition, the soundtrack needed effort to recordi bird, water and local environment sounds. These are all my own work.

Indie movies in Australia: the point of the situation

Are there other documentaries and documentarians that you respect, that you particularly love?

I continually seek out documentaries which contain no dramatisation. I am very interested in low budget run-and-gun documentary film makers. Unfortunately, I work very much alone.

What is the situation in Australia now for those who make independent cinema? And are you already creating any new projects?

I have recently finished a 25 minute documentary called Cargo Riders, shot in Sydney, Australia. A story about the life and times of a city bike rider’s co-op on a daily mission to live, to deliver and to celebrate. Their pleasure in their machines, in their group culture and in their lives is set to a backdrop of tasks, tattoos and family . The documentary explores the lives of four riders. Group culture is unique and is expressed in regular ‘check racers’ and the Cycle Messenger Australian Championships.

Conclusion

As a run-and-gun operator I aim to present true to life characters within their own stories. Sometimes place holds a truth as in my film Dyarubbin. Sometimes the story revolves around stories within stories based on character and image as depicted in Walls and Images. Where truth and character forms the bedrock a truth can be gently shocking as occurred in my indigenous film Jarjum.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision