The Italian film critic Emanuele Di Nicola met as Indiecinema’s member of staff the director of La Zona for Indiecinema, a documentary appreciated in the second edition of the festival

The Documentary Competition of the second edition of the Indiecinema Film Festival was the beginning of various cinephile discoveries. Some of these have found space, so far only in the online part of the festival. But even if in the meantime we have reached the third edition of the festival, we will take advantage of the first opportunity to propose them again in the cinema.

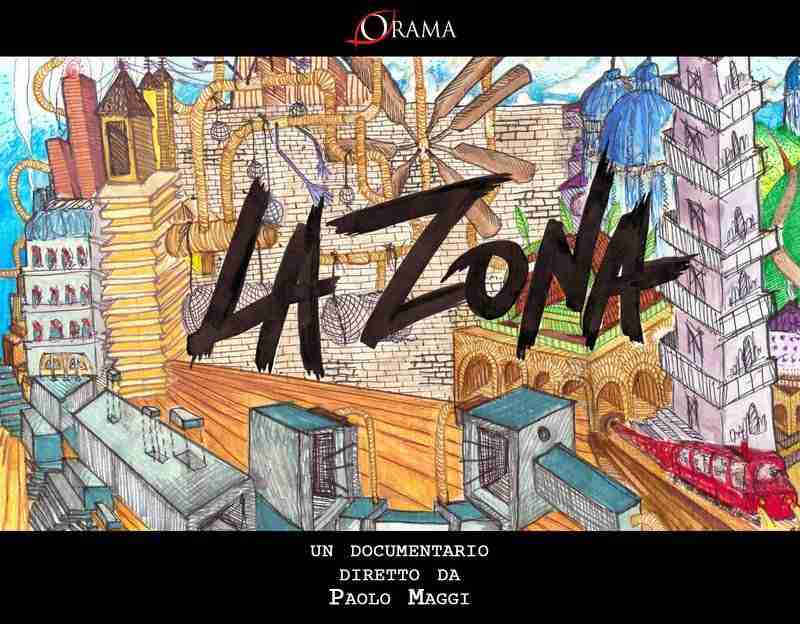

Meanwhile, we wanted to meet the author of La Zona, one of the most interesting documentaries selected between 2022 and 2023: mister Paolo Maggi

The doc’s beginning

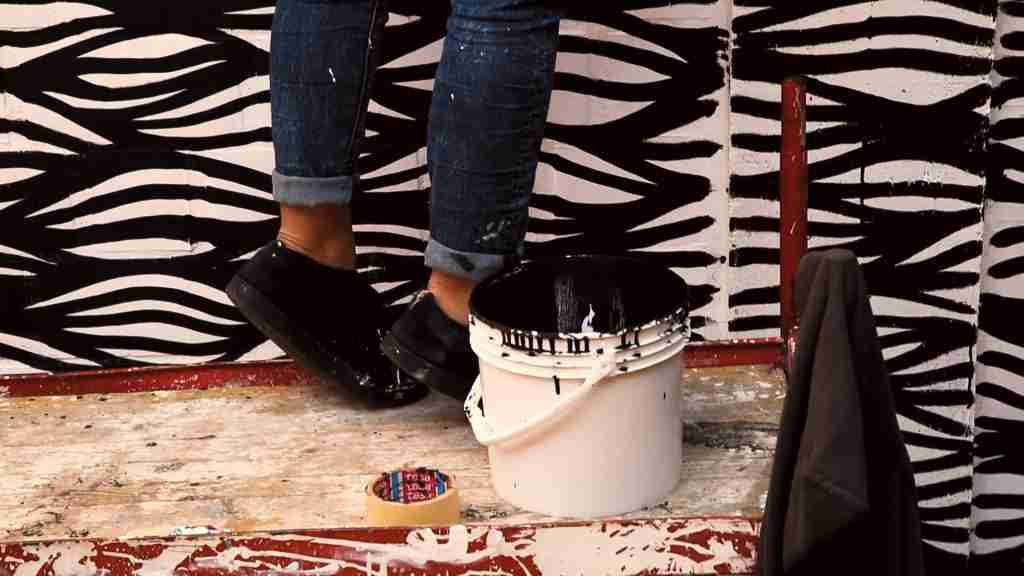

Your film La Zona, made in October 2017 and concluded in 2021, was selected for the Indiecinema Film Festival in 2022. It is a 42-minute documentary that enters the Gorki Civic Center, recently named in memory of the partisan William Michelini, in Bologna, in the Navile district. Fifteen artists repaint the walls of the centre, in short they bring it back to life. How did the idea of following this moment and making a documentary about it come about?

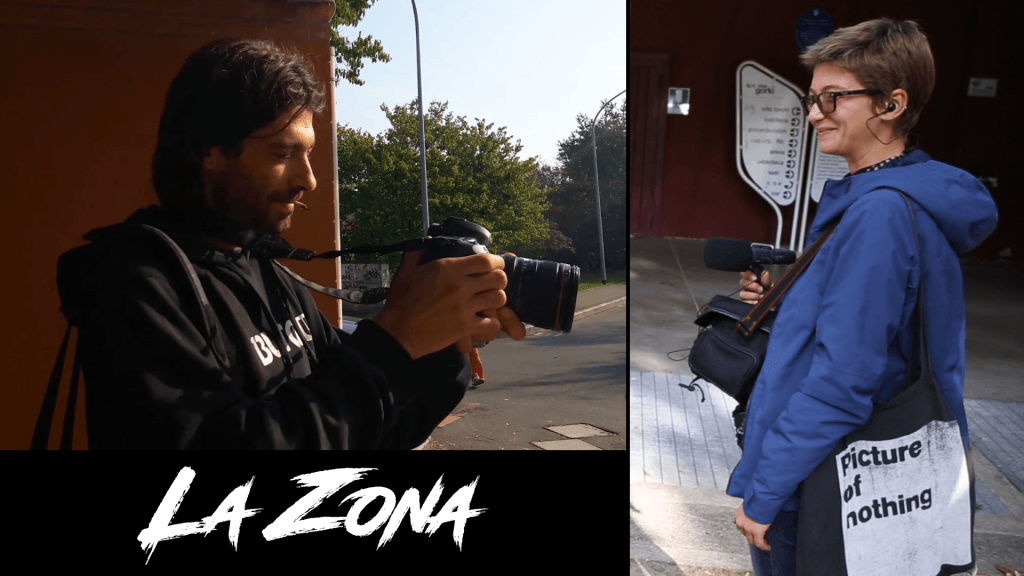

The film was born spontaneously, while we were shooting what was initially supposed to be a simple reportage. September 2017. Etta Polico, president of Serendippo, calls me, asking me to create, as a videomaker, a reportage for the event that would take place in October in the Bolognese suburbs of Corticella, Navile district, within the R.U.S.Co (Urban Recovery) project Spazi Comuni, entirely financed from the bottom through crowdfunding, which would have given new life to the Michelini Civic Center, creating Zona NG (acronym for Navile-Gorki), a real open-air museum. As far as I and my collaborator Iulia Stanescu were concerned, the work had to be completed in that first week, while the project would then move to the center of Bologna where three artists, Athena, Anneo and Awer, would paint a large wall in via Majorana left deteriorated over the years. We decide to follow them into the centre, just to take some shots before returning to Rome. However, something unexpected immediately happens that convinces us to stay. During this second week of filming we realized that what we were shooting was no longer (or perhaps never was) a reportage, but a real film, complete with sudden twists and turns that kept us continually in suspense wondering “how will end?”

In the film we meet activists, men and women, but also elderly people and children, a lot of inhabitants of the area. It is also a generational comparison between kids and more mature people. How did you gain their trust to get them in front of the lens?

The elderly and children have fun in front of the camera, giving us sincere and poetic moments. If you’re making a documentary about them, their neighborhood, their hopes, that’s it. They’re becoming characters in a movie, there’s a certain magic behind it all. With artists it was a little more complicated. They are led to see in the man behind the camera a ruthless and insensitive hunter of news, or rather of stories. It’s natural, many of them also do illegal things and often find themselves having to fight with ferocious journalists, and the stakes are very high. Iulia and I were certainly looking for conflicts, contradictions, but the point of view that interested us was theirs. We were on their side. And the only way we could make it heard on film was to share as many things as possible with them. We slept together on the floor in the spaces made available by the Sokos association, rather than accepting the very kind invitation to the homes of some residents of the neighborhood; we ate together, we dreamed together. It was total immersion, and despite this I think we never enjoyed their full trust.

Urban recovery

La Zona is the story of a recovery. There is a particular idea of supportive urbanity, which runs throughout the film. There is great citizen participation that wants to get this space moving again. In short, places must be experienced and cannot be abandoned to themselves. Do you agree, what is your idea of the city?

The city is something that belongs to us, and just as we take care of our garden, our living room, our car, so we should also show love towards the place where we live. And this feeling, which unfortunately has been somewhat lost in big cities, I still felt in Corticella. There is the gentleman who cuts the condominium hedge. Nobody asked him, he does it because he wants to live in a beautiful place. I think if we all did this, the world would be a wonderful garden.

Then there is the theme of art as a recovery tool. You took many images of the artists creating their works in the center. Sometimes it is said that writings smear the walls of our cities, a wrong and repressive approach that does not consider the artistic aspect. What do you think?

We must certainly distinguish what dirties from what embellishes. A wall is like an empty page, and as such it can also invite xenophobic writings or other vulgarity. We don’t realize that a mural can be a good deterrent for a possible scoundrel who passes through those parts.

Gorki is also a hub of activism. It is important to review it now, when the activists of the centers engage in new mobilisations, such as the one in favor of the Palestinian people. Yet too many still think that community centers “are where you hang out”. In your opinion, what is the importance of activists today?

Activists are the core of our society. And I’m talking about independent collectives. I have never had faith in institutions or parties and I have always been convinced that true politics, pure, antagonistic and without self-interest, is done from below. It’s a bit like the civic duty we have towards taking care of our neighborhood. We live in this world and we must fight, each in our own measure, to make it a better place to live.

The movie’s style end the processing times

Yours is a classic documentary. Many voices, many images come together to compose a story, or rather a moment, the rebirth of this space. What is your approach to documentary, who are your points of reference?

If I can be honest, I have never been a big fan of documentaries and, apart from those at festivals or particularly important ones, I have never seen too many of them. I make work video reports and I enjoy making short fiction films. Maybe you feel that I’m not a documentarian, I hope my spontaneity helped. Just as the report spontaneously became a film and we became its characters.

How was the process, how long did it take you to shoot it and then edit it?

Filming lasted about two weeks, the first in Corticella and the second in the center of Bologna. It’s the editing that suffered a bit. The crowdfunding money had run out and there was nothing left for postproduction. I continued editing while juggling the many commitments and projects I had to work on. The lockdown came to my aid by giving me a lot of free time in which I closed myself until I reached the final version of the film. As chance would have it, the judicial facts, a consequence of the events in Bologna, were resolved precisely in that period, thus accompanying the closure of our work.

Indie movies in Italy

In general, what are the difficulties you have encountered in making independent cinema in Italy today?

And what are the satisfactions? Lack of money is definitely a big limitation. It must be replaced by great passion, determination and the desire to get to the bottom by fighting against the many obstacles that we create for ourselves from time to time. But the satisfactions are countless. First of all, the realization itself, letting yourself be guided by the film itself, by the events, and seeing it come together practically under your own hands and eyes. Nobody dictated to us what we had to do or how to do it, so the film could take any direction and become whatever it wanted. And we let him do it. An advantage that independent cinema can certainly boast. And then the emotion it gave me during the various screenings, the participation of the spectators, the laughter, the cheering for the “heroes”, the disbelief towards the “bad guys”. Priceless.

Moving on to distribution, how has the film done? I know it has been screened several times in Bologna, of course, what are the prospects?

It was previewed in Bologna in September 2021, right in the little square of Corticella where it all began, in front of the “protagonists” of the film. And then the following summer in Piazza Lucio Dalla, guests of DiMondi Festival. For both evenings, provided by Etta Polico, we received money which covered, at least in part, the costs of post-production and distribution, again for Etta’s philosophy that “art is beautiful and must be paid for”. Finally it made a long tour of festivals, returning to Bologna to showcase at Visioni Italiane, passing as a finalist in various competitions in Veneto, Tuscany, Puglia and Sicily, and winning the special mention in the documentary section at the Latina Independent Film Festival. Now I’d like to screen it again during some independent cinema evenings, just to give it a final farewell on the big screen. But I also think the time has come for as many people as possible to see it, perhaps by handing it over to some streaming platform.

Can I ask you about your future plans?

I’m working on a new documentary film with a friend. And I have two more ideas ready to work on. Always documentaries, I’m now passionate about them. And then I would like to return to fiction. I’m looking for money for a short film I wrote. It is a more ambitious project than my previous ones, and without funds it is not possible to do it. So strength and courage, other challenges are calling us!

Emanuele Di Nicola