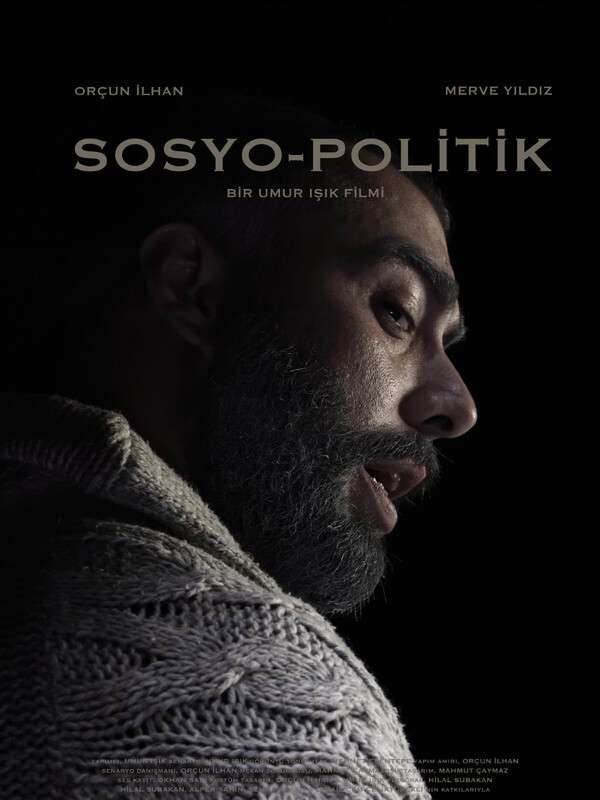

Chatting with the director of Sosyo-politik (Socio-political, in English), a brilliant feature film selected for the third edition of Indiecinema Film Festival

A writer seeks refuge in a storm and finds it in a retired factory worker’s house. As the night continues things turn out to not be what they seem and the two with sinister plans try to out do each other in a fight in order to exist and be free. This is the plot of Sosyo-politik, an extraordinary surprise from the Indiecinema Film Festival‘s feature film competition, suspended between theatrical language, forms of estrangement and underground tensions of contemporary society. We talked about it with the Turkish director Umur Işık, who told us some very interesting things about his work!

The background of Sosyo-politik and the formal choices

Hi, Umur! Before talking about the film that we appreciated and willingly selected for the festival, I mean “Sosyo-politik” (2023), can you tell us something more about your artistic training and your previous works? We know for example that you have directed at least two other movies,”Röportaj: Izmir” (2019) and “Untitled” (2021)…

Of course, ever since I’ve known myself I was a lot more into stories that I’ve heard about fantastic creatures and fables and I’ve always loved watching little films whatever the genre be. As I’ve grown older I found myself in a more mathematical environment, I was guided to Software Engineering by my teachers etc, but I loved writing on my own time and had several short stories that I’ve finished but never really showed anyone. Somewhere along the way something changed and I decided I didn’t want that to be “just a hobby”, I wanted that as a profession. So, I quit Software Engineering and hop on a bus to another city to study Theatre Criticism and Dramaturgy there I’ve met people that inspired me, mentored me to make my very first short film Röportaj: İzmir (or Interviews of a City: Izmir)” and I just kept going.

The studying I’ve done at the university was more of a cultural one that helped me on my ideas and connecting some dots about what I really wanted to do, but in practice I learned everything from a couple of people that kept inspiring and encouraging me and by the method of try and fail. Also keep in mind I am still actively learning and training in the arts by not limiting myself on one thing and always going through with the ideas that keeps popping up and not being scared to fight the fights while I can.

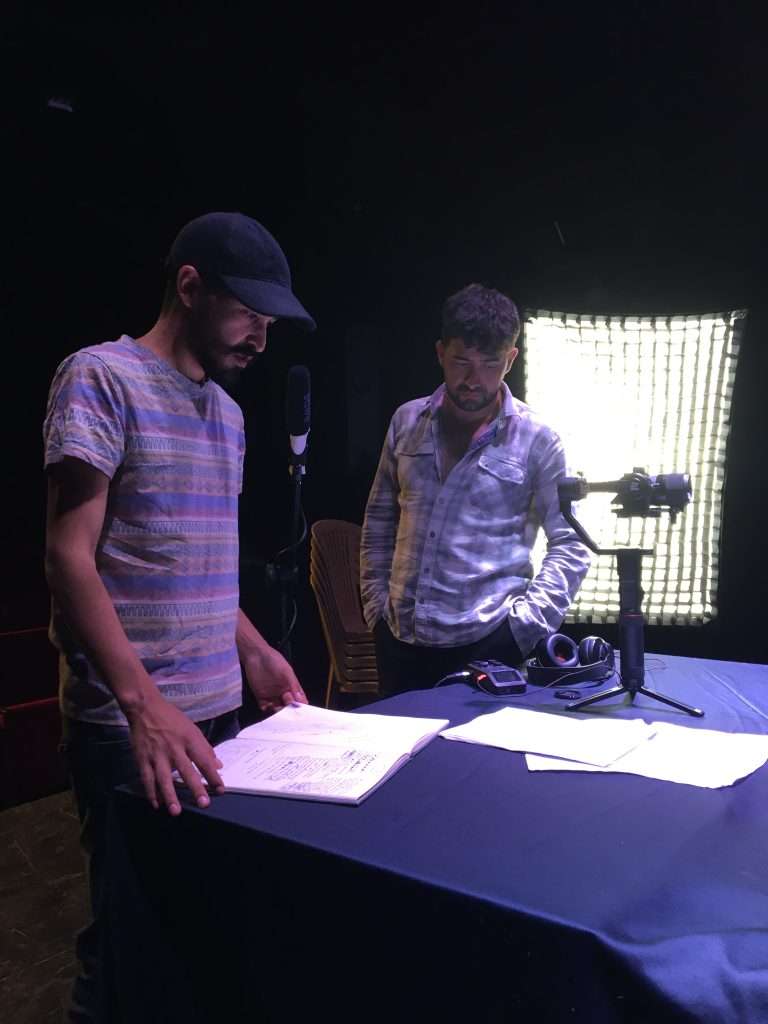

The biggest influence and mentor to all my art is also present in my works as well sometimes you can see him as a script advisor, sometimes as an art director and in Sosyo-Politik (or Socio-Political)” that man can be seen as the lead actor, Orçun İlhan.

In “Sosyo-politik” we found an apparently austere form, but enriched by a great wealth of ideas: noir

atmospheres, a metalinguistic structure, references to theatre, split-screen… where did the main idea

come from and how did such a complex formal apparatus take shape?

The idea of Sosyo-Politik first came as a theatre play but as I kept writing it started to turn into a film that I really loved the idea of. A writer and an evolved character, a fight for the meaning of existence, to not die, to have “freedom”.

We live in a time of uncertainty, things change everyday and there are billions of revolutions that take place that gets replaced the day after. Militarism seems to be on the rise everywhere, opinions no longer are referred as opinions but rather as tools of a unseen psychological warfare. Poverty and corruption is seen plainly all around the globe, yet the people are less talkative about it. Thus came the background of the “Yellow Vests Protests of France” something that seemed hopeful and righteous to my eyes. I can’t go without mentioning the book “The Weight of the World” (La Misère du monde) by Pierre Bourdieu, because that book had a great impact on the film as well, I suggest to everyone that took an interest to our film to go check that out as well.

The references to theatre and the structure came from my interest on the old theatre and the ideas of one Antonin Artaud. The split-screen or as some would call it “shot in shot” scenes came from the wanting of change, of not wanting people to focus a single point that they’ve chosen on the big screen but rather feel overwhelmed or intrigued by the specific shots that are placed on spots that does not feel natural so the focus of the audience can only shift on a non-linear way that might take them a bit more closer to the screen, to focus what is about to be said. And of course there’s a reflection of the “times of uncertainty…” lines I threw at the paragraph above.

Meta-theatre, actors and alienating soundtrack

Going into details, such a film shows a strong interest in theater and meta-theatre, from You. So can you tell us how this theatrical and literary passion entered into the creation of the work?

Mostly the passion comes from the ideas of Antonin Artaud and the Theatre of Cruelty, ever since I read that I felt a strong pull to those ideas and how theatre or in general art should be made. And to be fair I’m not much of a theatre guy, I love to work within the lenses and the editing room. And to be fair again, I’ve never seen a play that made me feel like somebody was doing Artaud and his views justice. I’ve seen films do that, but never theatre. I felt like what Artaud wanted from the theatre required more technology than they had at the time, and for today, that idea of the art could be born again but it would be more accurate on film. So willingly or not willingly I put those ideas and the passions to my work whenever I shoot.

We also admired an extraordinary couple of actors, who alone carry an hour of film. What can you tell us about them and how did you choose them?

Their names are Orçun İlhan and Merve Yıldız. I’ve known both of them for about seven years now, all three of us were in the same university studying Theatre Criticism and Dramaturgy.

Orçun İlhan is an active figure in the entertainment industry for eighteen years, an actor and a screenwriter but an artist on all ends. He writes, directs, acts on theatre plays, tv shows, films, worked as an art director on many projects, draws, designs on all levels. Most of his time nowadays goes to the theatre companies he owns which are called “Celil Yağız Kültür Sanat” (Celil Yağız Culture and Arts) and one called “Maymun Kral Company” (Monkey King Company). Also being my mentor (even though he doesn’t like being called a mentor because it makes him look old) has influenced me a lot during these seven years. Him being in the movie was a direct call by myself without an audition, the role was written specifically for him.

Merve Yıldız was a young and aspiring actress when we met, and has shown the ability to work more and better than the most in the industry. She auditioned for the role of Gaspard alongside other candidates. The role was originally for a male actor but despite the role being a male Merve was the outstanding one among them all so we did some small changes the role to be more fitting to a woman.

After graduation she went on to start a theatre company called “MY Tiyatro” (MY Theatre).

The use of the soundtrack also seemed subtle and ironic to us, as it interacts with the text exploring its different potential, from the dramatic one to the sitcom itself (with laughter in the background). Why this choice?

The making of a film requires the filmmaker to think in different dimensions at different times. The writing should tell a story with a chosen direction, the directing should tell a different story that supports and helps the chosen direction and the editing with the sound design should tell a third story that also supports and helps the chosen direction. The soundtrack came to be six months after the film was done filming so my views on it were drastically different than how I started moving with the writing or the shooting. The sitcom part was there from the start, even at the screenplay there was laughter in the background but the idea didn’t quite work out on the shooting and kinda turned out to be less effective than what we anticipated but we were still quite happy about it. The idea behind it were the character “Pierre” was putting on a talkshow like performance after he gave a restart to the story, because he was getting bored with the same old conversations trying to get a different result.

From the particular relationship with off-screen to the distribution problems

What seemed courageous on an aesthetic (and political) level was instead that continuous calling into question of the public, through the protagonist’s glances into the camera or other references to something (or someone) off-screen, accused in a certain sense of indifference, of not knowing or wanting to take a stand upon what happens in society. Is our explanation correct in some way?

Yes, your explanation for the choices we’ve made is quite correct, we tried to shock and get the attention of the audience by looking directly at them and speaking directly at them. This was my way of speaking on the issues and the unstable way of our lives at today’s world and the reasons for it being us, the public, showing a blind eye to it all.

How is the visibility of “Sosyo-politik” progressing? Has it already had theatrical distribution in Turkey or is it currently running at various festivals?

It had a special screening only available to the crew and the families of the crew, other than that the film is currently running at various festivals. We hope to achieve a theatrical distribution for it around June when the festival run is over.

More generally, and to worthily close our conversation, I would like to ask you what we asked your colleague Cevahir Çokbilir just an year ago, that is, whether there are interesting spaces at the moment for indie movies in Turkey.

Unfortunately the answer to this questions is a negative. Turkey is not a country that respects or helps artists or any kind of art form since the start of the 2010s and it only gets worse as time goes on. We filmmakers either work at government friendly films that speaks certain values and ideas or we work independently out of our own pockets with close to no chance of getting a distribution on Turkish soils.

Or we deal with our worldly famous directors acquiring more than 80 percent of the government fund for cinema works given by the Minister of Culture, leaving us with scraps to fight for (which we can’t even hope to get if we speak on political or social values that doesn’t align with the government). We hope that a change is coming to our beautiful country as we keep making these films but people getting locked up for their forms of arts or getting sued by the government for speaking on values that doesn’t align with theirs more and more as the times goes on.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision