Suspense cinema is not a genre; it is a philosophy. It is the art of manipulating time, evoking anxiety, and delaying the inevitable. The collective imagination is marked by the great masters, from Alfred Hitchcock to David Fincher, who transformed tension into a visual epic. These masterpieces defined the rules of the game, creating a universal language of fear and anticipation.

But beyond narrative tension, a deeper suspense exists, one not based on action, but on atmosphere. It is an investigation into the human soul, into the unknown that lurks not in external monsters, but in the cracks of our own psyche. It is here that the lack of expensive special effects is compensated by an iron-clad script, character depth, and a masterful use of light, sound, and editing.

This “aesthetic of scarcity” generates a more visceral authenticity. This guide is a journey across the entire spectrum. It is a path that unites the great masterpieces of the genre with the most innovative independent works. These are films that do not just tell stories, but question, disorient, and leave an indelible mark, proving that true suspense is not what is shown, but what is suggested.

Part I: Labyrinths of the Mind – Conceptual Psychological Thrillers

This section is dedicated to films that conceive of narration as a puzzle box. They are works that weaponize structure, ambiguity, and unreliable perception to create a form of intellectual suspense. They demand active viewing, transforming the spectator from a passive observer into a detective trying to piece together a fragmented reality.

Memento

Leonard Shelby is an insurance investigator whose life is shattered by his wife’s murder. Due to a head injury sustained during the attack, he suffers from anterograde amnesia, which prevents him from creating new memories. To track down the killer, he relies on a system of Polaroids, notes, and tattoos, trying to piece together a puzzle whose image fades every few minutes.

Memento is not a film about memory loss; it is the cinematic experience of memory loss. Christopher Nolan, with a modest budget but a brilliant idea, does not just tell the story of his protagonist’s condition but imposes it on the viewer through a revolutionary narrative structure. The color sequences, which proceed backward, throw us into the same state of confusion as Leonard: each scene begins without the context of what preceded it. The suspense arises not from the question “what will happen next?” but from a distressing and continuous query: “why did what we just saw happen?” The black-and-white sequences, which move forward chronologically, provide an anchor, an apparent linear path to the truth. When the two timelines converge in the finale, the revelation offers not catharsis, but an existential vertigo. We realize that memory is not a reliable archive, but a narrative we construct to survive. It is a masterpiece of psychological suspense that demonstrates how the greatest innovation can arise not from an unlimited budget, but from the perfect fusion of form and content.

Donnie Darko

Donnie Darko is a troubled teenager who is awakened one night by a mysterious voice. He follows the voice and meets Frank, a disturbing figure in a rabbit costume, who announces the end of the world in 28 days. While he is outside, a jet engine crashes into his bedroom. Saved by this surreal event, Donnie begins to navigate between apocalyptic visions, time travel, and the typical anxieties of adolescence.

Independent cinema is the only place where a work as boldly unclassifiable as Donnie Darko could have been born. Richard Kelly blends teen drama, philosophical science fiction, and psychological thriller into a unique amalgam that defies every label. The film’s suspense derives not from a conventional threat, but from its deep and persistent ambiguity. Is Donnie a paranoid schizophrenic or a “Living Receiver” tasked with saving a tangent universe from destruction? The film refuses to give a definitive answer, and it is in this uncertainty that its strength lies. The narrative immerses us in a dreamlike, almost Lynchian atmosphere, where the logic of the real world unravels. The unease arises from the feeling that the forces at play are cosmic and incomprehensible, and that the fate of a single individual is tied to that of the entire universe. It is a cult film precisely because its suspense does not end with the viewing but continues to resonate in the viewer’s mind, inviting them to reassemble the pieces of an existential puzzle with no single solution.

Mulholland Drive

A dark-haired woman survives a car crash on Mulholland Drive but loses her memory. She takes refuge in a Hollywood apartment, where she is discovered by Betty Elms, a hopeful aspiring actress. Together, the two women try to uncover the identity of the mysterious “Rita,” venturing into a world of dreams, secrets, and dangers hidden behind the glittering facade of the City of Angels.

David Lynch, the ultimate auteur, uses suspense not as a plot mechanism, but as a state of mind, a pervasive atmosphere that permeates every frame. Mulholland Drive is a narrative labyrinth that operates according to the logic of a dream, where tension arises not from the fear of what might happen, but from the feeling that reality itself is unstable and on the verge of collapse. The first part of the film is an illusion, the idealized dream of Diane Selwyn, a failed actress, who reinvents herself as the talented and innocent Betty. In this dream, she transforms the woman she loves and who rejected her, Camilla, into the vulnerable and dependent Rita. The suspense is a thin veil covering an abyss of pain, jealousy, and failure. Lynch guides us through this dreamscape with recurring symbols—a blue key, a mysterious box—that act as anchors in a sea of surrealism. The brutal transition from the dream to the squalid reality in the final third of the film is the real twist: the accumulated suspense is discharged not in an explosion of violence, but in an emotional implosion. It is a film that must be “felt” before it is understood, an experience that demonstrates how the deepest suspense is that which arises from the mystery of identity itself.

Pi

Max Cohen is a solitary and paranoid math genius, convinced that everything in nature can be understood through numbers. Using a self-built supercomputer in his Chinatown apartment, he tries to decipher the patterns of the stock market. His research leads him to discover a mysterious 216-digit number, which attracts the attention of both a powerful Wall Street firm and a sect of Kabbalistic Jews.

Darren Aronofsky’s debut is a sensory assault, a micro-budget psychological thriller that transforms paranoia into an aesthetic. Shot on a shoestring budget on high-contrast black-and-white film, Pi is not just a stylistic choice but the visual representation of its protagonist’s fractured and obsessive mind. Max’s world is binary: order and chaos, black and white, rationality and madness. The grainy, overexposed photography immerses us in his claustrophobic perspective, while Clint Mansell’s electronic score, combined with diegetic sounds like drills and drips, becomes the sonic transposition of his excruciating headaches. The suspense is not tied to a physical antagonist but to Max’s descent into the spiral of his own obsession. The search for a universal order becomes a curse, and the viewer is dragged into this feverish quest, forced to wonder where genius ends and madness begins. It is proof that independent cinema can create a totalizing and terrifying experience with minimal means, relying solely on the strength of a radical authorial vision.

Primer

Two young engineers, Aaron and Abe, work on tech projects in their garage. During an experiment aimed at reducing the weight of objects, they accidentally discover an unexpected side effect: a time machine. Initially, they use it for small gains in the stock market, but soon their discovery drags them into a vortex of paradoxes, duplicates, and paranoia, testing their friendship and their very perception of reality.

Primer is perhaps the most extreme example of intellectual suspense, a film that categorically refuses any compromise with the viewer. Made on a budget of only $7,000, Shane Carruth’s film is an hermetic work that relies on dense, jargon-filled dialogue and an incredibly complex plot. The suspense arises not from the fear of an external threat, but from the intellectual terror of failing to understand the implications of what is happening. Carruth places us in the same position as his protagonists: we are witnesses to a revolutionary discovery, but we are just as incapable of controlling its consequences. The film’s minimalist aesthetic—the time machine is a simple gray box, the locations are anonymous garages and storage units—anchors the science-fiction idea in a prosaic reality, making it even more unsettling. The real tension of the film is the disintegration of trust between Aaron and Abe. The ability to alter the past destroys their relationship, creating a labyrinth of double-crosses and multiple versions of themselves. Primer is an experience that requires multiple viewings, a puzzle that demonstrates how the most effective suspense can derive not from clarity, but from a deep and deliberate confusion.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision

Coherence

During a dinner party among friends, the passage of a comet causes a blackout. When the power goes out, the group notices that only one house down the street is still lit. Some of them decide to go ask for help, but they return with a box containing their own photos, taken that same evening. They soon realize that the comet has fractured reality, creating an infinity of parallel universes and identical houses.

Coherence is a miracle of low-budget cinema, a striking demonstration of how a single location and a brilliant idea can generate breathtaking suspense. Shot almost entirely in director James Ward Byrkit’s own home with a largely improvised script, the film draws its strength from its very production methodology. The tension is not just written, it is lived: the actors, who were given only their characters’ motivations day by day, convey an authentic confusion and paranoia. The premise, based on the Schrödinger’s cat paradox and quantum decoherence, transforms a normal dinner party into an existential nightmare. The suspense grows exponentially as the characters—and the viewer—lose all points of reference. Who is the “real” friend and who is a double from another reality? The house, a symbol of security, becomes a prison of distorting mirrors, where every decision can catapult the characters into a slightly different and more dangerous version of their lives. It is a psychological thriller that plays on our deepest fears: the loss of identity and the fragility of human relationships.

A Better Life

Drama, thriller, by Fabio Del Greco, Italy, 2007.

Rome: Andrea Casadei is a young investigator specializing in audio wiretapping who conducts investigations commissioned by husbands betrayed by their wives, or by parents worried about what their children are doing outside the home. But what interests him most is understanding the human soul, listening to casual conversations in the streets, knowing what people think. He often meets in Piazza Navona with his friend Gigi, a frustrated street artist obsessed with success at all costs, with whom he shares a passion for wiretapping. Shocked by the mystery of the disappearance of Ciccio Simpatia, another street artist common friend, Andrea decides to abandon the commissioned works to seek a better life and reflect on his own and others' existence. He will meet the actress Marina and with a bug he will slowly enter her life until he discovers her most unthinkable secrets. The film deals with an important theme of contemporary Western society: the lack of love. The mysterious and tormented figure of Marina is reflected in a gloomy and soulless Rome.

Director Fabio Del Greco declared about his film: "Perhaps this film is a reflection on the art of observing, of listening, in short, of what one does when one leaves the real world to tell about it. Perhaps he wants to talk about the subtle relationship between the mirages of success touted by today's society, power and the most authentic human relationships.A 'dark cloud' hangs over the city: it is engulfing everyone in a sort of indistinct, uniform mass, where everyone thinks the same things, where everyone they are more alone. Where is the truest part that makes us unique? Maybe you can try to intercept it only secretly."

LANGUAGE: Italian

SUBTITLES: English, Spanish, French, German, Portuguese, Dutch.

Following

A young, unemployed writer, seeking inspiration, begins to follow random people through the streets of London. He imposes strict rules on himself to avoid being discovered, but soon breaks them, attracting the attention of one of the men he is tailing. The man reveals himself to be Cobb, a charismatic thief who introduces him to the world of burglary. The writer is thus drawn into a dangerous game of manipulation and deceit.

Before Memento and Inception, Christopher Nolan laid the groundwork for his labyrinthine cinema with this zero-budget debut. Following is a lean and essential neo-noir that already contains all the DNA of its author: a fascination with complex narrative structures, an obsession with identity and deception. Shot in 16mm black and white, the film transforms its production limitations into stylistic strengths. Its non-linear structure, which jumps between three different moments in the protagonist’s life, is not a stylistic whim but a narrative necessity. It allows Nolan to build the mystery and suspense piece by piece, revealing information in a fragmented way and forcing the viewer to question everything they see. The tension arises from the protagonist’s progressive loss of control, a voyeur who goes from being an observer to a pawn in a game much larger than himself. It is a debut feature that demonstrates how a strong authorial vision can shape a compelling thriller even with the most meager means, laying the foundation for one of the most significant careers in contemporary cinema.

Oldboy

Oh Dae-su, an ordinary man, is kidnapped and imprisoned in a hotel room for fifteen years without any explanation. During his captivity, he learns from television that he has been framed for his wife’s murder. Suddenly released, he is given a cell phone, money, and new clothes. He begins a violent and desperate quest for revenge to discover the identity of his jailer and the reason for his torture.

A masterpiece of South Korean cinema and the central chapter of Park Chan-wook’s “Vengeance Trilogy,” Oldboy is a brutal descent into the abyss of the human psyche. The film transcends the boundaries of the revenge thriller to become a modern Greek tragedy, where the suspense lies not only in the mystery of “who” and “why,” but in the devastating psychological impact of such prolonged isolation. Captivity transforms Dae-su into an obsessed beast, a man whose humanity has been eroded to its core. The violence, though stylized and at times hyperbolic, is never gratuitous; it is the physical expression of his inner torment. Park Chan-wook builds tension through a relentless pace and a series of shocking revelations. However, the film’s true stroke of genius is its ending. The discovery of the truth does not lead to the liberating catharsis of revenge, but to a psychological revelation so atrocious that it completely destroys the protagonist. The suspense transforms into existential horror, proving that some truths are more unbearable than imprisonment itself and that revenge is a cycle that consumes those who seek it.

Part II: The Horror of the Soul – Existential and Social Suspense

This chapter shifts from the enigmas of the mind to the horrors of the soul. These films use the grammar of suspense and horror to explore deep and often terrifying real-world themes: generational trauma, social oppression, grief, and the anxieties of existence. The monster is rarely just a monster; it is a metaphor made frighteningly literal.

Get Out

Chris, a young African American photographer, is preparing to meet the parents of his white girlfriend, Rose. Despite his concerns, the Armitage family proves to be overly welcoming. However, a series of bizarre encounters and the unsettling behavior of the family’s Black servants cause a growing unease in Chris, leading him to uncover a terrifying secret beyond all imagination.

With Get Out, Jordan Peele coined the term “social thriller,” redefining the potential of the genre. The film is a masterclass in suspense that finds horror not in the supernatural, but in the very fabric of American society. The threat is not a masked monster, but the smiling, seemingly progressive face of liberal racism. The suspense is masterfully built through micro-moments: a misplaced comment, a stare that lingers too long, an atmosphere of forced politeness that hides a latent hostility. Peele uses powerful symbolism to articulate his critique. The “Sunken Place” is a brilliant metaphor for the marginalization and paralysis of the Black voice in the face of systemic oppression. The teacup, a symbol of bourgeois civility, becomes a tool of mental control. The film brilliantly subverts horror clichés: the isolated house is not haunted by ghosts, but by the legacy of slavery and the exploitation of the Black body. Get Out demonstrates that the most effective suspense is that which is rooted in real and collective fears, transforming a social anxiety into a tangible nightmare.

The Babadook

Amelia, a widow still grieving the violent death of her husband, struggles to raise her troubled six-year-old son, Samuel. One night, Samuel finds a disturbing pop-up book titled “Mister Babadook” and asks his mother to read it to him. The story is about a dark creature that, once you are aware of its existence, can no longer be driven away. Soon, a sinister presence begins to manifest in the house.

The Babadook is one of the most powerful cinematic allegories about grief and depression. Director Jennifer Kent uses the tools of horror cinema to give shape to an otherwise invisible emotion. The Babadook is not an external entity, but the physical manifestation of Amelia’s unresolved trauma, her repressed grief, and her growing resentment towards a son whose birth coincided with her husband’s death. The film’s suspense is entirely psychological and grows in tandem with the protagonist’s mental deterioration. The key phrase from the book, “The more you deny me, the stronger I get,” is the film’s central thesis. It is Amelia’s refusal to face her pain that allows the “monster” to take control, transforming the home from a refuge into a psychological prison. The ending is of a rare depth for the genre: the Babadook is not defeated, but confronted, accepted, and confined to the basement, fed like a dark pet. It is an extraordinary metaphor for the process of living with one’s own demons, an ending that elevates the film from a simple horror to a profound meditation on mental health and human resilience.

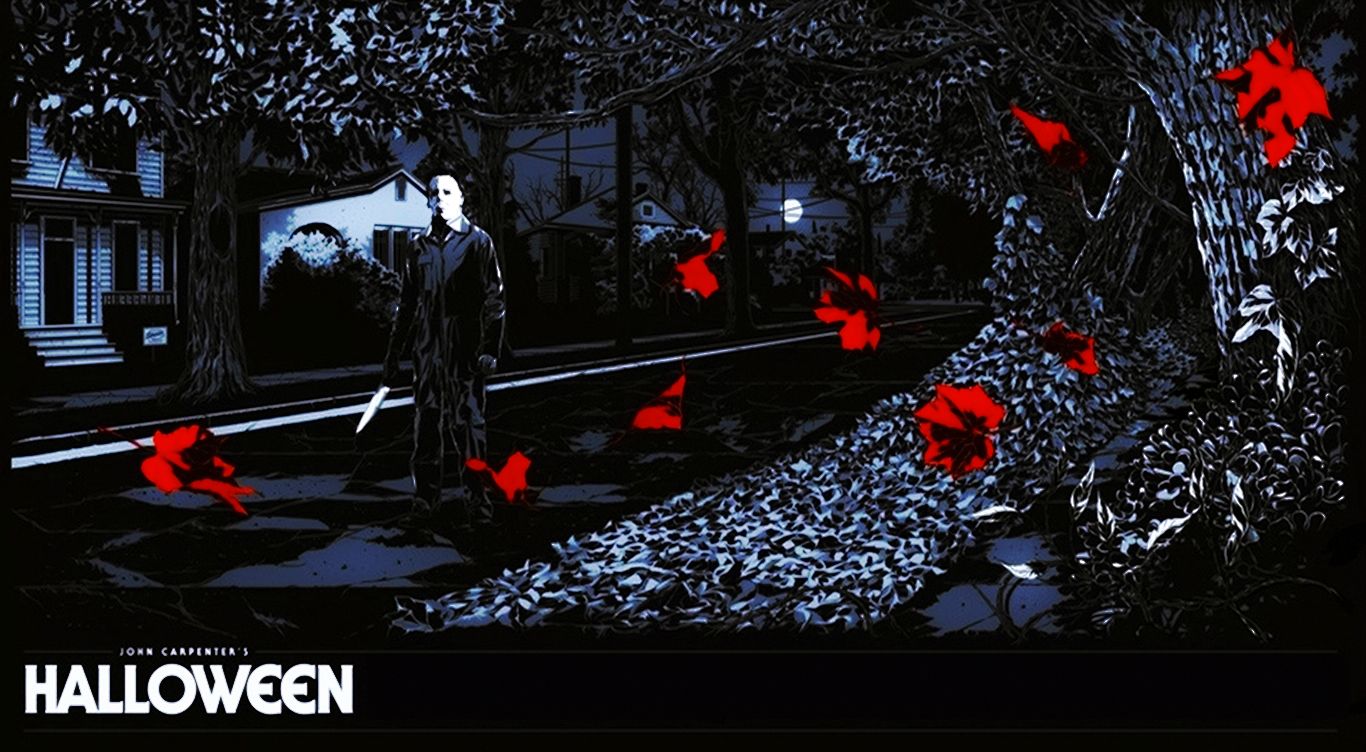

Halloween

Horror, by John Carpenter, United States, 1978.

An independent film shot on a very small budget, it grossed over $ 80 million worldwide at the time. It is the most successful slasher movie and one of the 5 most profitable films in the history of cinema, which has become a cult with countless sequels and reboots. Carpenter describes the remote American province in an extraordinary way and raises the tension for over an hour, without anything happening, with a linear and effective direction, and with hypnotic music created by himself. A brilliant director who manages, with a few simple elements and a small production, to create a horror destined to remain in the worldwide cinematic imagination.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

It Follows

After a seemingly innocent sexual encounter, nineteen-year-old Jay discovers she is being pursued by a supernatural force. This entity, which can take the form of anyone, follows her slowly but relentlessly. The only way to get rid of it is to pass the curse on to someone else through sexual intercourse. Together with her friends, Jay must find a way to escape a horror that is always just a few steps away.

It Follows intelligently subverts the “sex equals death” horror cliché. In David Robert Mitchell’s film, sex is not a transgression to be punished, but the vehicle for a curse that functions as a powerful and layered metaphor: it can represent sexually transmitted diseases, trauma, or more universally, mortality itself. The suspense is built on a simple but brilliant idea: the threat is not fast or aggressive, but slow, constant, and unstoppable. This characteristic generates a pervasive, low-frequency anxiety, turning every person in the background, every figure walking in the distance, into a potential danger. The atmosphere is crucial. The film is immersed in a timeless aesthetic, mixing modern and retro elements, creating a dreamlike and suspended atmosphere, as if the story were taking place in a universal suburban nightmare. Mitchell’s direction is masterful in creating a sense of constant paranoia, using wide shots and slow camera movements to force the viewer to scan the horizon, just like the protagonists. The horror lies not in the jump scare, but in the inescapable awareness that, no matter where you go, “it” is following you.

The Witch

In 1630s New England, a Puritan family is banished from their community and settles on the edge of a foreboding forest. Their devout faith is tested when their newborn son mysteriously disappears. As the harvest fails and paranoia creeps in, the family begins to suspect that their teenage daughter, Thomasin, is a witch, unleashing a spiral of accusations, fear, and horror.

Robert Eggers, with an almost documentary-like philological rigor, creates a work of suspense that is as much a horror film as it is a historical drama. The strength of The Witch lies in its disconcerting authenticity. Using dialogue drawn from diaries and court records of the era, and photography lit almost exclusively by natural light, Eggers transports us to a world where witchcraft was not a fantasy, but a terrifying and tangible reality. The suspense arises not so much from the witch hiding in the woods, but from the psychological disintegration of the family itself. Isolation, hunger, and a suffocating religious fanaticism become fertile ground for suspicion and hysteria. The true horror is the ease with which family love turns into mortal hatred, fueled by fear of the unknown and the search for a scapegoat. The film deliberately leaves open the question of whether the evil is an external supernatural force or a manifestation of the family’s fears and repressed desires. It is this ambiguity that makes The Witch such a profoundly unsettling experience, an immersion into an era where the line between faith and madness was dangerously thin.

Hereditary

After the death of her enigmatic mother, miniature artist Annie Graham tries to process her grief with her family. However, a series of tragic and terrifying events begins to haunt them, revealing dark secrets about their lineage. The family finds themselves fighting against a sinister and seemingly inescapable force that threatens to destroy them from within, revealing that some legacies cannot be refused.

Ari Aster’s debut is a work of surgical cruelty and precision, a film that blends family drama with occult horror in an almost unbearable way. Hereditary is terrifying not only for its shocking images but because it roots its horror in an incredibly real emotional pain. The suspense is built on a foundation of unbearable grief. The first half of the film is a devastating portrait of a family disintegrating under the weight of tragedy, guilt, and unexpressed resentment. The supernatural element emerges from these psychological wounds, transforming generational trauma and mental illness into a literal curse. Toni Collette’s performance is monumental, a tour de force that traces a woman’s descent into madness, or perhaps, into an even more frightening truth. Aster grants no respite, building a sense of inevitability that becomes increasingly suffocating. Every detail, every miniature created by Annie, is a piece of a diabolical puzzle that comes together in the end. Hereditary is a film that demonstrates how the deepest horror is not the fear of death, but the fear of what we inherit, consciously or not, from our own family.

Under the Skin

A mysterious woman drives a van through the streets of Scotland, luring lonely men. She seduces them with the promise of an intimate encounter but leads them into a surreal trap: a black, liquid space where their bodies are consumed and reduced to empty shells. This alien entity, however, begins a slow and confusing journey of discovery, starting to perceive fragments of a humanity she cannot comprehend.

Jonathan Glazer’s film is a hypnotic and profoundly unsettling work of science fiction, a sensory experience that generates suspense through the unknown and alienation. Told almost entirely from the detached perspective of the creature played by Scarlett Johansson, the film forces us to look at our world with outside eyes. The tension derives not from a conventional plot, but from the cold, clinical atmosphere, the mystery of the alien’s motives, and the terrifying nature of her predatory method. Mica Levi’s dissonant score and the surreal images of the “black room” create a sense of cosmic horror. However, the core of the film is its existential journey. As the entity interacts with the world, particularly when she shows an unexpected act of pity towards a disfigured man, she begins to question her mission. The suspense shifts from fear for her victims to fear for herself, a creature lost in a world she doesn’t understand and which ultimately proves hostile. It is a bold exploration of the themes of identity, objectification, and empathy, a thriller that leaves more questions than answers.

Silent night, bloody night

Horror, by Theodore Gershuny, United States, 1972.

1972 American Slasher, is a forerunner horror genre several years before Carpenter's Halloween, with a complex script and first person shooting of the killer, which inspired many subsequent films. Its originality and its narration are what manage to make it a small and little known pearl of the genre. A series of murders in a small New England town on Christmas Eve after a man inherits a family estate that was once a madhouse. Many of the cast and crew members were former Warhol superstars: Mary Woronov, Ondine, Candy Darling, Kristen Steen, Tally Brown, Lewis Love, director Jack Smith, and graduate Susan Rothenberg.

LANGUAGE: english

SUBTITLES: italian, french, spanish

Parasite

The Kim family lives in a squalid semi-basement apartment, struggling for survival. When the son, Ki-woo, gets a job as an English tutor for the daughter of the wealthy Park family, he devises a plan to get all his family members hired, pretending they don’t know each other. The infiltration is successful, but their precarious symbiosis is threatened by a shocking discovery hidden in the foundations of the luxurious villa.

Although Parasite is a masterpiece that blends black comedy, drama, and social satire, its second half transforms into a suspense thriller of rare intensity. Bong Joon-ho is a master at using space and architecture as a metaphor for class struggle. The Park’s villa, with its modern and airy aesthetic, is built on a vertical hierarchy that reflects the social one: the Parks live on the upper floors, the Kims infiltrate the ground floor, and an even darker secret lurks in the basement. The suspense is generated by the precariousness of the Kims’ plan. The threat of being discovered is constant and culminates in one of the most tense sequences in modern cinema: the one where they hide under the living room coffee table while the Parks, unaware, discuss their “smell,” an indelible mark of their social class that they cannot wash away. In Parasite, the real “monster” is not a person, but the systemic inequality of capitalism, an invisible force that drives people to desperate acts. The film demonstrates how the most effective suspense can arise not from the fear of physical danger, but from the anxiety of losing one’s place in the world.

The Killing of a Sacred Deer

Steven Murphy is a brilliant cardiac surgeon with a seemingly perfect life: a beautiful wife, two children, and an impeccable home. His orderly existence is disturbed, however, by his strange friendship with Martin, a fatherless teenager. When Steven introduces Martin to his family, inexplicable and terrifying events begin to manifest. Martin reveals to Steven that he must make an unthinkable sacrifice to atone for a past transgression.

Yorgos Lanthimos transposes the Greek tragedy of Iphigenia in Aulis to a sterile American suburb, creating a work of clinical and unbearable anguish. The suspense in The Killing of a Sacred Deer is not emotional, but cerebral and glacial. The director’s distinctive style, characterized by monotonous dialogue and deliberately unnatural performances, generates a strange and absurd atmosphere. The tension arises from the cold and inescapable logic of Martin’s curse: an archaic, almost biblical justice that befalls a modern and rational world. The impossible choice imposed on Steven—to sacrifice a member of his family to save the others—is the engine of an existential horror. There are no rational explanations; the characters are trapped in a fate that defies medical and scientific logic. Lanthimos forces us to confront the idea of a guilt that demands a terrible price, creating a film that is as much a psychological thriller as it is a mythological nightmare, where the greatest fear is the helplessness in the face of an absurd and cruel justice.

Part III: Claustrophobic Tension – The Art of Siege and Isolation

This part focuses on a classic suspense trope perfected by independent cinema: the siege narrative. When a large budget for sprawling locations is not an option, directors turn inward, transforming a single place—a house, a room, an island—into a pressure cooker of escalating tension. These films demonstrate that the most terrifying prisons are those with locked doors and no way out.

Green Room

A broke punk rock band, the Ain’t Rights, accepts a last-minute gig at an isolated club in the Oregon woods. After the concert, they discover the venue is a neo-Nazi den. When one of the band members witnesses a murder in the green room, the group barricades themselves inside, beginning a violent and desperate siege for survival against a ruthless enemy.

Jeremy Saulnier orchestrates a siege thriller of almost unbearable brutality and effectiveness. The suspense in Green Room is visceral, physical, and immediate. There is no time for psychological introspection; there is only the primal struggle to survive. The titular green room becomes both a refuge and a deadly trap, a claustrophobic microcosm where the tension is palpable. Saulnier deconstructs the heroism typical of the genre: the protagonists are not action heroes, but scared and unprepared musicians whose decisions are often dictated by panic. The violence is depicted realistically and unpleasantly, without any aesthetic gloss. The horror arises not from stylistic elegance, but from the chaotic and clumsy brutality of the situation. Every escape attempt, every improvised plan, only increases the pressure and reduces hope, making Green Room a tense and breathless experience, a perfect example of how a confined space can become the stage for the purest horror.

The Invitation

Will reluctantly accepts a dinner invitation to the home of his ex-wife, Eden, whom he hasn’t seen in two years, following the tragic death of their son. The evening, which reunites a group of old friends, is pervaded by a strange, forced cheerfulness and an increasingly unsettling atmosphere. Will, still tormented by grief, begins to suspect that Eden and her new partner have a sinister ulterior motive for the gathering.

Karyn Kusama’s The Invitation is a masterpiece of slow-burn psychological suspense, set entirely in a single, luxurious house in the Hollywood Hills. Unlike a conventional thriller, the tension is not generated by immediate violence, but by a creeping social discomfort, gaslighting, and growing paranoia. The film masterfully exploits the protagonist’s grief. Will’s trauma makes him an unreliable narrator, and for much of the film, the viewer is forced to wonder if the threat is real or just a projection of his fragile mind. Kusama builds suspense through subtle details: a locked door, a disturbing video, the presence of strangers with ambiguous behavior. The beautiful house, a symbol of success and well-being, progressively becomes a suffocating prison. The explosion of violence in the finale is all the more effective because it comes after an excruciating wait, a slow burn that has brought the tension to a boiling point. It is a film that demonstrates how the deepest fear can arise from the suspicion that the people we once loved have become dangerous strangers.

Slow life

Drama, comedy, thriller, by Fabio Del Greco, Italy, 2021.

Lino Stella takes a period of vacation from his alienating job to devote himself to relaxation and his passion: drawing comics. But he did not foresee certain disturbing elements: the intrusive administrator of the building where he lives, the postman who delivers crazy fines and tax bills, an overbearing security guard, a very enterprising real estate agent, the old lady downstairs who raises the feline colony of the condominium. These characters will make his vacation hell.

Food for thought

The larger a social group is, the more rules and bureaucracy are needed, which often do not respect the individual. You have to learn to live with annoying people, but sometimes the social pressure and arrogance can become intolerable. The only laws that always come to our aid are the laws of Nature.

LANGUAGE: Italian

SUBTITLES: English, Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

The Lighthouse

In the late 19th century, two lighthouse keepers, the old and gruff Thomas Wake and the young Ephraim Winslow, begin a four-week shift on a remote, storm-battered island. The isolation, hard work, and the secrets they both hide lead to a rapid descent into madness, fueled by alcohol, mythological hallucinations, and growing paranoia.

Robert Eggers imprisons us in a claustrophobic and feverish nightmare, a psychological thriller that explores the fragility of the human psyche under conditions of extreme isolation. The Lighthouse is a total sensory experience. The choice to shoot in an expressionistic black and white and in an almost square aspect ratio (1.19:1) is not a mere stylistic whim, but a tool to amplify the feeling of oppression and entrapment. The suspense is existential and hallucinatory. Reality deforms, the boundaries between the two men blur, and the island itself seems like a living, malevolent creature. The film is steeped in maritime mythology and literary references, from Prometheus to Proteus, which transform the struggle for sanity into an archetypal battle between man and unknowable forces. The tension grows in a crescendo of drunkenness, violence, and grotesque visions, culminating in the obsessive question that haunts Winslow: what is in the lighthouse’s light? The answer, when it comes, offers no clarity, only the abyss of madness.

Goodnight Mommy

Two ten-year-old twins, Elias and Lukas, await their mother’s return to their isolated country home. When she arrives, her face is completely covered in bandages following cosmetic surgery. Her behavior is cold, distant, and cruel, and she begins to completely ignore Lukas. The boys become convinced that the woman under the bandages is not their real mother and decide to find out the truth by any means necessary.

Goodnight Mommy is a chilling and disturbing psychological thriller that plays with the Freudian concept of the uncanny: the transformation of the familiar into something strange and terrifying. The house, a modern and sterile environment, becomes a theater of psychological warfare between an unrecognizable mother and her suspicious sons. The suspense is built slowly, through an atmosphere of silence and distrust. The bandages on the mother’s face are a powerful visual device, dehumanizing her and turning her into a monstrous “other” in the children’s eyes. The directors, Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala, are masters at manipulating the viewer’s perspective. For much of the film, we are led to sympathize with the twins and doubt the mother’s identity. The violence, when it erupts, is brutal and hard to watch, forcing us to question who the real victim is. The final twist is not a simple narrative trick, but a tragic key that re-contextualizes the entire story, revealing it as a horrifying exploration of trauma, grief, and the fracture of the child psyche.

The House of the Devil

In the 1980s, Samantha, a college student short on cash, accepts a well-paying babysitting job in an isolated house. Her employers, a creepy elderly couple, reveal that there is no child, but she must simply look after their elderly mother. As she explores the large Victorian house during a lunar eclipse, Samantha realizes she is at the center of a terrifying satanic ritual.

Ti West pays a masterful homage to the horror of the ’70s and ’80s, replicating not only its aesthetics (the film grain, the title fonts) but, more importantly, its rhythm. The House of the Devil is an exercise in slow-burn suspense, building tension through anticipation and atmosphere rather than action. For much of the film, almost nothing happens. The suspense is all in the air, in the sense of foreboding that something terrible is about to occur. The isolated house is the true protagonist. The long tracking shots that follow Samantha as she wanders through the empty rooms, hearing strange noises and discovering unsettling details, create a palpable sense of terror. West plays with the viewer’s expectations, delaying the revelation of the horror as long as possible. When the satanic ritual finally begins, the explosion of violence is all the more shocking because it comes after an hour of meticulous suspense-building. The film draws on the cultural anxiety of the “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s, demonstrating how the most effective fear is that which feeds on an almost unbearable wait.

Part IV: Unsettling Realism – Stories on the Edge of Truth

This section examines films that draw their suspense from a chilling sense of realism. They subvert genre expectations by anchoring their stories in the plausible, the mundane, and the uncomfortably familiar. The horror here lies not in the fantastic, but in the recognition that these events could happen.

Nightcrawler

Lou Bloom is a desperate and unscrupulous man who discovers the world of “nightcrawling”: the nocturnal hunt for accidents, fires, and violent crimes to film and sell to local news stations. With sociopathic determination, Lou pushes further and further, manipulating crime scenes and endangering the lives of others to get the perfect shot and climb the hierarchy of television journalism.

Dan Gilroy’s film is a fierce and chilling critique of the cynicism of modern media and our own voyeuristic hunger for shocking content. The suspense of Nightcrawler derives not from an external threat, but from observing the terrifying rise of its protagonist. Lou Bloom is not a conventional monster; he is a toxic product of unbridled capitalism, a man who applies business logic to human horror. Jake Gyllenhaal’s performance is central: his ravenous gaze, his unsettling calm, and his self-help manual language make his amoral actions even more disturbing. The tension is rooted in watching him cross one ethical line after another, without ever hesitating. The viewer becomes a accomplice, a voyeur of his success, implicated in the same media consumption that the film condemns. It is a realistic and ruthless thriller that shows how, in the news market, the line between observer and participant can become dangerously thin.

The stranger

Thriller, by Orson Welles, United States, 1946.

Orson Welles, a filmmaker who has always been against the Hollywood system, did not like this film made inside the studios, but strangely he managed to create a commercial product beyond his own expectations, managing to insert his unmistakable style into it, leaving us an amazing movie. In the small town of Harper, lives Charles Rankin, who is about to marry the daughter of an important judge. But Charles Rankin is actually Frank Kindle, a Third Reich criminal who has created a new identity for himself. However, Inspector Wilson is on the trail of him.

Food for thought

Forget the untruths. For a while, you may feel a certain boredom, fear or lack of motivation: while what is false disappears, it takes time for what is real to assert itself. There will be a transition period. Let it happen, and hold on. Sooner or later your masks will fall, the falsehoods will dissolve, and your true face will appear.

LANGUAGE: english

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, Germa, Italian, Portuguese

Blue Ruin

Dwight is a homeless man living in his old, battered car. His apathetic existence is shaken when he discovers that the man who killed his parents has been released from prison. Driven by a desire for revenge, Dwight, a clumsy and inexperienced killer, returns to his hometown to carry out his mission, triggering a brutal and senseless feud with his enemy’s family.

Blue Ruin is a masterful deconstruction of the revenge thriller. Jeremy Saulnier dismantles the myth of the infallible and cathartic avenger, replacing him with a frighteningly real protagonist. Dwight is not an action hero; he is an ordinary man, terrified and blatantly incompetent, whose quest for revenge is more an act of desperation than of strength. The violence in the film is realistic, graceless, and profoundly unsatisfying, depriving the viewer of the gratification typical of the genre. The suspense arises not from the anticipation of heroic action, but from the constant fear that Dwight’s ineptitude will lead to his death and from the horror of a senseless cycle of violence that feeds on itself. The minimalist aesthetic and sparse dialogue accentuate the sense of desolation and realism. It is a film that explores the dirty and tragic consequences of revenge, demonstrating that in the real world, violence only begets more violence, in a spiral of ruin.

Reservoir Dogs

Six criminals, who do not know each other and use color-coded aliases, are hired for a diamond heist. However, the job goes wrong due to a police ambush. The survivors find themselves in an abandoned warehouse, wounded and bleeding. Paranoia spreads quickly as they try to figure out what went wrong and, most importantly, who among them is the traitor.

Quentin Tarantino’s explosive debut redefined crime cinema, creating a new kind of thriller based not on action, but on dialogue, characters, and a non-linear narrative structure. The genius of Reservoir Dogs lies in never showing the heist. The entire film is the aftermath, the paranoid and claustrophobic account of a failure. The suspense is entirely psychological and focuses on a single, burning question: who is the mole? Tarantino builds tension through brilliant, pop-culture-infused dialogue that reveals the personalities and power dynamics among the characters. These long verbal exchanges are interrupted by sudden and brutal explosions of violence, making the atmosphere even more unstable and dangerous. It is a film that established the unmistakable style of a great independent auteur, proving that the most compelling suspense can be created in a single room, with a group of men talking and pointing guns at each other.

Searching

When David Kim’s sixteen-year-old daughter goes missing, he turns to the police. But after 37 hours with no leads, David decides to search the one place no one has checked yet: his daughter’s laptop. In a race against time, David must trace his daughter’s digital footprints before she disappears forever, discovering a world of secrets he never imagined.

Searching is a pioneer of the “screenlife” thriller, a genre born from our hyper-connected reality. The entire narrative unfolds through computer screens, smartphones, and surveillance cameras. This formal choice is not a simple gimmick, but a powerful tool for creating a uniquely modern form of suspense. The tension is built through actions we perform every day: the movement of a cursor, the typing and deleting of a message, the scrolling of a social media feed. These digital gestures become vehicles for emotion and suspense. As David delves into his daughter’s online life, he discovers a person he didn’t know, an abyss between her public and private identity. The film is a profound reflection on parental fear in the digital age and the loneliness that can hide behind a screen. It is a realistic and incredibly engaging thriller that demonstrates how cinematic language can evolve to tell the anxieties of our time.

Creep

Aaron, a videographer struggling financially, responds to an online ad for a one-day job. His client, Josef, is an eccentric man who, suffering from a terminal illness, wants to record a video diary for his unborn son. What begins as a strange but harmless day slowly turns into a psychological nightmare, as Aaron realizes that Josef is much more unstable and dangerous than he seems.

Creep is an exercise in minimalist suspense that makes the most of the found footage format. With only two actors and one main location, Patrick Brice’s film generates enormous tension starting from social discomfort and a growing unease. The heart of the suspense is Mark Duplass’s chameleonic performance as Josef. His character unpredictably oscillates between being playful, pathetic, and threatening, keeping both the protagonist and the viewer in a constant state of alert. You never know what to expect from him, and this unpredictability is terrifying. The found footage format makes the experience uncomfortably intimate and plausible, drawing on the real fear of meeting a stranger from the internet whose friendly facade hides dark intentions. It is a film that proves that to create fear, you don’t need monsters or special effects, just the unpredictability of human behavior.

The Blair Witch Project

In 1994, three film students venture into the woods of Maryland to shoot a documentary about the local legend of the Blair Witch. They disappear, and a year later, their footage is found. The film is the edit of this “found” material, documenting their descent into fear and desperation as they get lost and are haunted by an invisible and terrifying presence.

The Blair Witch Project not only popularized the found footage genre but revolutionized how low-budget horror is conceived. Its impact was devastating because it understood a fundamental principle of fear: what you don’t see is infinitely more frightening than what you do. The film’s suspense is created entirely through suggestion, sound design, and the viewer’s imagination. The witch never appears. The horror is in the nocturnal sounds, the piles of stones, the stick figures hanging from the trees. The realism is amplified by the improvised dialogue and the genuine reactions of the actors, who were tormented by the crew off-camera to elicit authentic fear. The film masterfully blurred the line between fiction and reality, thanks in part to one of the first viral marketing campaigns on the Internet that presented the actors as actually missing. It is a seminal work that demonstrated that the purest suspense needs no budget, only a deep understanding of the psychology of fear.

Part V: Avant-Garde Visions – Suspense as a Sensory Experience

This final selection celebrates filmmakers who push the boundaries of what a suspense film can be. These are works driven by a strong authorial vision, where tension is as much a product of aesthetic choices—cinematography, sound, editing rhythm—as it is of the plot. They are visceral, stimulating, and often unforgettable sensory experiences.

Ex Machina

Caleb, a young programmer, wins a contest to spend a week at the isolated residence of Nathan, the brilliant and reclusive CEO of his company. There, he discovers he has been chosen to participate in an experiment: to interact with the world’s first true artificial intelligence, embodied in a beautiful robot named Ava. What begins as a Turing test transforms into a complex psychological game of seduction and manipulation.

Alex Garland’s film is an elegant and cerebral science fiction thriller that builds suspense not on action, but on dialogue and intellectual tension. Set almost entirely in a minimalist and claustrophobic bunker, the film is a three-way chess match, where every conversation is a battle of wits between Caleb, his arrogant creator Nathan, and the enigmatic Ava. The suspense is psychological and philosophical in nature: is Ava truly conscious or is she just simulating? What are her true intentions? The clean and sterile aesthetic of the location contrasts with the complex and messy moral questions the film raises about consciousness, creation, and gender power dynamics. It is a work that fascinates and unnerves, demonstrating that suspense can arise from the big questions about the nature of humanity and the intelligence we seek to create in our own image.

Burning

Jong-su, an aspiring writer living on the fringes of society, happens to run into Hae-mi, an old childhood friend. When she returns from a trip to Africa, she introduces him to Ben, a rich, charming, and mysterious man. The fragile balance between the three is broken when Hae-mi suddenly disappears. Obsessed with her disappearance, Jong-su begins to suspect Ben and his strange hobby: burning abandoned greenhouses.

Burning is a masterpiece of atmospheric suspense, a slow-burn mystery where the tension lies not in the events, but in the ambiguity and the unsaid. Lee Chang-dong adapts a Haruki Murakami short story and transforms it into a feverish investigation into obsession, impotent rage, and class resentment in contemporary South Korea. The central question—what happened to Hae-mi?—never finds a definitive answer. The suspense is entirely existential, nestled in the uncertainty that consumes the protagonist. The film is a powerful social commentary: Jong-su’s obsession with Ben is fueled by a toxic mix of jealousy, suspicion, and class envy. Ben, with his effortless wealth and emotional detachment, represents an inaccessible world that torments Jong-su. It is a profoundly unsettling cinematic experience that lingers long after viewing, leaving the viewer to meditate on the elusive nature of truth and the anger simmering beneath the surface of modernity.

Uncut Gems

Howard Ratner is a charismatic jeweler in New York’s Diamond District and an incurable gambling addict. Perpetually in debt and pursued by loan sharks, he believes he has found the solution to all his problems in a rare, uncut black opal from Ethiopia. But his addiction to risk drags him into a frantic and self-destructive spiral of ever-higher stakes, endangering his family, his business, and his own life.

The Safdie brothers’ film is not a thriller; it is a two-hour panic attack. It is a masterclass in creating relentless and stressful suspense, a sensory experience that offers no respite. The directors’ distinctive style is the key to everything: overlapping dialogue, a chaotic sound design, claustrophobic close-ups, and a frantic pace that mirrors the protagonist’s chaotic and adrenaline-fueled mind. The suspense derives not from a mystery to be solved, but from witnessing a man’s self-destruction in real time. Every decision Howard makes raises the stakes, every phone call brings a new threat, every bet is a matter of life or death. It is an immersive and suffocating character study, a portrait of gambling addiction where the tension never lets up. Uncut Gems is an exhausting and unforgettable experience that pushes the viewer’s ability to endure anxiety to its limit, proving that suspense can be a form of sensory assault.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision