Cinema has always had a deep bond with poetry. The collective imagination is marked by unforgettable works that have used verse to change lives, like the iconic Dead Poets Society, or that have told the tormented biographies of great poets. These films transform the written word into an emotional epic, making poetry accessible and powerful.

But the connection between cinema and poetry is even deeper. It is not just about telling stories about poetry, but about creating a “cinema of poetry.” As Pasolini theorized, it is a cinema that doesn’t just tell stories; it evokes moods, creates visual metaphors, and sculpts time. It is a language that, like poetry, works by subtraction, association, and rhythm, capable of extracting lyricism from reality itself.

This guide is a journey across the entire spectrum. It is a path that unites the great masterpieces that brought verse to the big screen with the most radical underground works. We will explore biopics that seek the soul behind the biography, narrative films where poetry is the engine of the action, and, finally, radical works where cinema itself becomes pure visual poetry.

Part I: Lives of a Poet – The Auteur Biopics

The auteur biopic rarely settles for mere chronicle. It rejects hagiography to immerse itself in the inner turmoil, the creative process, and the socio-political rebellion of the poet. These are not historical portraits, but cinematic séances, attempts to capture an ineffable soul through light and shadow.

Total Eclipse (1995)

In late 19th-century France, the established poet Paul Verlaine invites the very young and brilliant Arthur Rimbaud to Paris. The meeting marks the beginning of a relationship as passionate as it is destructive, a whirlwind of alcohol, sex, and violence that will drag them on a journey across Europe and towards self-destruction, forever marking the history of literature.

Agnieszka Holland does not film poetry; she unleashes it on the screen. Hers is a physical, visceral cinema that translates the aesthetic of the “cursed poets” into a bodily experience. The relationship between Rimbaud (a young and dazzling Leonardo DiCaprio) and Verlaine (a sorrowful David Thewlis) is not just the story of a love affair, but the staging of an aesthetic: that of breaking the rules, of seeking the absolute through the derangement of the senses. The film embodies the archetype of the poet as a rebel, a fallen angel whose art is born from the mud of his own damnation.

Bright Star (2009)

London, 1818. The young and outspoken Fanny Brawne, a fashion enthusiast, becomes fascinated by her neighbor, the talented but penniless poet John Keats. A secret and intense love blossoms between them, hindered by social conventions and his frail health. Their story becomes inextricably intertwined with the creation of some of the most celebrated poems of English Romanticism.

In stark contrast to the fury of the cursed poets, Jane Campion creates a cinema of sensations that mirrors Keats’s romantic soul. By telling the story from Fanny’s point of view, the director immerses the viewer in a tactile and luminous world. The photography, the costumes, the sounds of nature are not a simple backdrop but become the very substance of the film. Bright Star is a visual poem, a delicate ode that demonstrates how cinematic language can carry the same grace and poignant beauty as a verse by Keats.

Howl (2010)

The film reconstructs the birth and impact of “Howl,” the poem that consecrated Allen Ginsberg and became the manifesto of the Beat Generation. The narrative unfolds on three levels: the historic public reading of 1955, the 1957 obscenity trial against publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and an interview in which a mature Ginsberg reflects on his life and art.

Howl is a bold and layered work, a film-essay on the very nature of poetry and its interpretation. Directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman do not simply tell a story; they stage a debate. The trial represents society’s attempt to cage the verse in a legal definition, the interview provides the author’s personal context, but it is the third level that is revolutionary: animated sequences, created by Eric Drooker (a collaborator of Ginsberg himself), that visualize the poem’s anarchic and visionary power. Animation thus becomes a form of literary criticism through images, the only way to translate the irreducible energy of “Howl” without betraying it.

Neruda (2016)

Chile, 1948. Senator and poet Pablo Neruda opposes the government and is declared a public enemy. Forced into hiding, he begins a daring escape across the country, pursued by a tenacious but imaginary police inspector, Óscar Peluchonneau. The manhunt transforms into a literary game, a duel between the poet and his unlikely antagonist.

Pablo Larraín directs a brilliant “anti-biopic,” a film uninterested in historical truth but in the power of myth. Neruda is not a film about the poet, but a Nerudian film, adopting the playful, political, and self-mythologizing style of its subject. The figure of the policeman, a complete fabrication, becomes a genius metaphor: he is the secondary character who dreams of becoming the protagonist, the shadow chasing the body, the reader pursuing the author. The film explores the construction of a legend, showing that Neruda’s greatest poem was, perhaps, his own life.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision

A Quiet Passion (2016)

Confined to her family home in Amherst, Massachusetts, Emily Dickinson lives a secluded existence, marked by relationships with her family and a deep spiritual crisis. Behind the facade of a reclusive life lies a brilliant mind and a rebellious spirit, pouring her passion, her pain, and her unique vision of the world into hundreds of poems.

Terence Davies crafts a portrait of Emily Dickinson that is as rigorous in its form as it is explosive in its emotions. The director’s style, made of slow camera movements, painterly compositions, and dialogue as sharp as blades, perfectly mirrors the poetry of his protagonist: short, structured, almost claustrophobic verses that contain a universe of passion. The house’s interiors become a physical and psychological prison, a visual metaphor for the social constraints against which the poetess fought with her only weapon: the word.

Feast

Documentary, by Franco Piavoli, 2018, Italy.

Franco Piavoli, author of the masterpiece "The Blue Planet", returns to the director to capture the "evening of the day of celebration", between Leopardi and Pascoli. A journey between the poetic and the anthropological. What is a "party"? What does it represent, from a symbolic and material point of view? What burdens, or what relieves, does it bring to people's minds? And what value does it take when it turns into a collective act? It does not need any tinsel, Festa, and arrives right in the spectator's heart without stratification, without any deviation from the path, without any addition.

Language: Italian

Subtitles: English

Pasolini (2014)

The film reconstructs the last hours of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s life, on November 1, 1975. From dinner with Ninetto Davoli to an interview with Furio Colombo, from the meeting with his mother to the final, fatal journey to the Idroscalo of Ostia. Reality mixes with dreamlike sequences that stage chapters of his unfinished projects, Petrolio and Porno-Teo-Kolossal.

Abel Ferrara’s film is not a biopic, but an evocation, a séance. An outsider filmmaker pays homage to another, and does so by adopting his gaze. Ferrara’s raw, direct, at times dreamlike style merges with Pasolini’s material, creating a work that does not seek answers about the murder but investigates the mystery of the man and the artist. It is a film about the body, the word, death, and the violent collision between art and power, a cinematic testament that imagines the cinema Pasolini was never able to make.

Before Night Falls (2000)

Based on the autobiography of the Cuban poet and novelist Reinaldo Arenas, the film traces his life: from a poor childhood to his participation in the Castro revolution, up to the brutal persecution by the regime due to his homosexuality and dissident writing. A harrowing journey through prison, censorship, and exile, sustained by an indomitable will to express himself.

Director and painter Julian Schnabel brings Arenas’s story to the screen with a lyrical and impressionistic approach. His camera does not merely document the horrors of repression but constantly seeks the beauty, sensuality, and poetry that the protagonist managed to find even in the most desperate circumstances. The film thus becomes a powerful hymn to the resilience of the human spirit and to art as the supreme form of survival. For Arenas, poetry is not a luxury but a necessity, the only way to remain free in a world that wants to annihilate you.

An Angel at My Table (1990)

Based on the autobiographies of New Zealand writer Janet Frame, the film follows her life journey, from a childhood marked by poverty and family tragedies to a misdiagnosis of schizophrenia that leads her to spend eight years in psychiatric hospitals, undergoing hundreds of electroshock treatments. Her salvation will be her writing, which will earn her a literary prize and, finally, her freedom.

Jane Campion creates a portrait of extraordinary sensitivity, exploring the inner world of a woman whose unique perception of reality is labeled as madness by society. The film visualizes a “poetic consciousness,” showing how Janet’s sensitivity, shyness, and imagination, considered symptoms of an illness, are in fact the source of her artistic genius. It is a moving work about the fragility and strength of creativity, and a denunciation of the brutality of institutions that try to normalize what they do not understand.

Wilde (1997)

The film focuses on the adult life of Oscar Wilde, from his marriage to Constance Lloyd to the fatal and scandalous relationship with the young Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas. This bond will lead him to a head-on collision with Bosie’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, and to the trial that will decree his public ruin and sentence him to two years of hard labor.

Supported by a monumental performance from Stephen Fry, who seems born to play Wilde, the film captures the tragic duality of its protagonist: the sparkling wit of the public intellectual and the vulnerability of the private man. The film suggests that Wilde’s life itself was his greatest work of art, a continuous performance of style and intelligence. His downfall was not just the consequence of a forbidden love, but the tragic epilogue of the clash between an individual who lived poetically and a society that could not tolerate the truth behind the artifice.

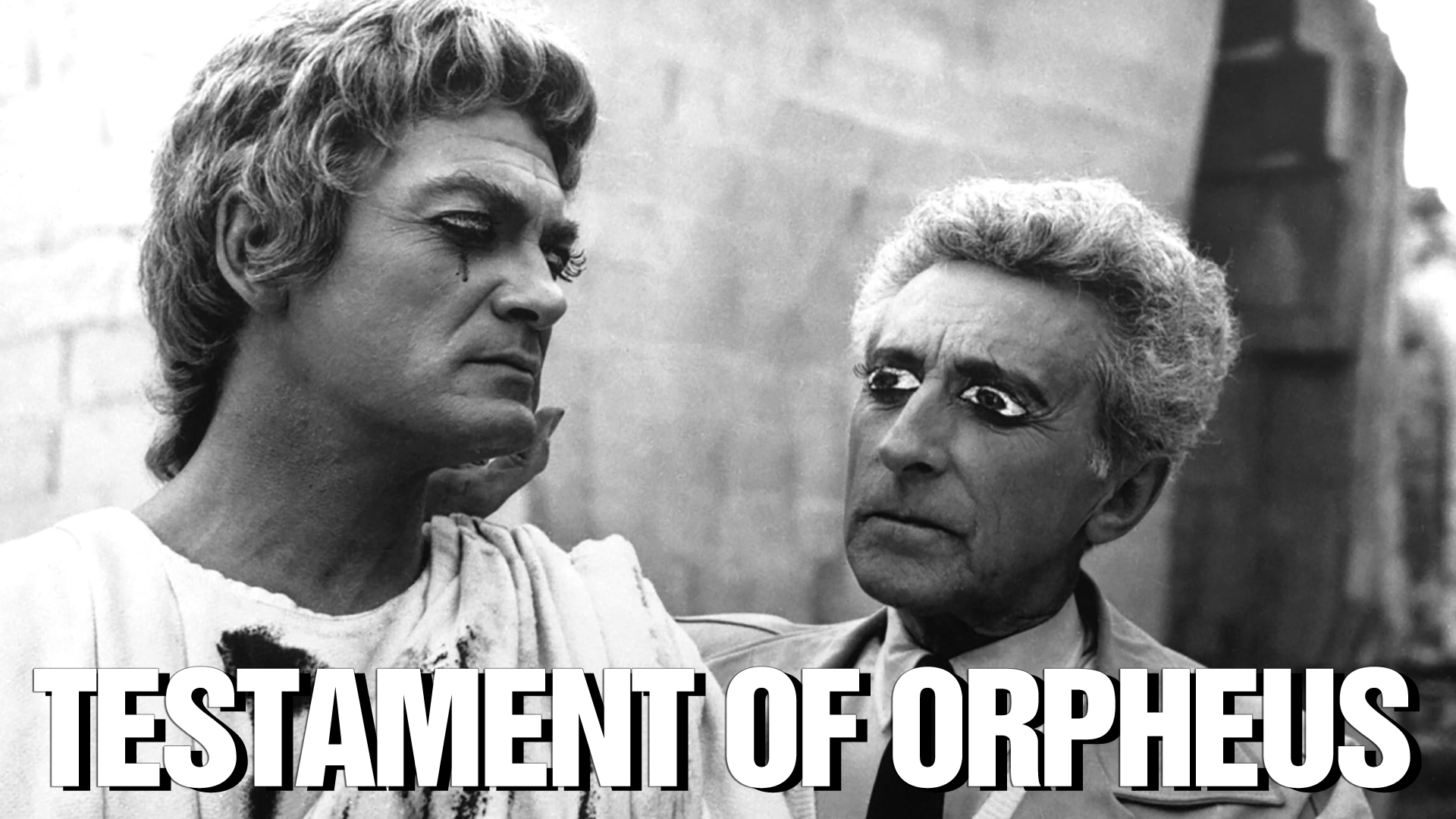

Testament of Orpheus

Drama film, by Jean Cocteu, France, 1960.

In his latest film, the legendary Jean Cocteau is a poet who travels through time in search of enlightenment. In a mysterious wasteland, he meets lost souls that result in his death and resurrection. With an exceptional cast including Pablo Picasso, Jean-Pierre Leáud, Lucia Bosè, Yul Brynner, Brigitte Bardot, Testament of Orpheus closes Cocteau's extraordinary research on the relationship between art and life.

LANGUAGE: french

SUBTITLES: english, italian

Part II: The Word Becomes World – Poetry as Narrative

In these films, poetry is not just quoted or discussed; it is an active force. It becomes a tool of seduction, a catalyst for change, a secret language that allows characters to see the world—and themselves—in a new light. It is the demonstration that verse can leave the page and become destiny.

Paterson (2016)

Paterson is a bus driver in the city of Paterson, New Jersey. His life is marked by a reassuring routine: waking up, work, walking the dog, a beer at the bar. In his spare time, Paterson writes poems in a secret notebook, drawing inspiration from the small details of his daily life and the conversations he overhears on his bus.

Jim Jarmusch directs a work of disarming delicacy, a manifesto against the romantic idea of the tormented poet. The film celebrates the poetry of the everyday, the hidden beauty in repetition and observation. The very structure of the film, cyclical like a work week or a bus route, becomes a poetic form. Paterson tells us that to be a poet, one does not need great dramas, but an attentive gaze and an open heart, capable of finding “the marvelous in the everyday.”

Endless Poetry (Poesía sin fin, 2016)

The second part of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s visionary autobiography, the film recounts his youth in Santiago in the 1940s and ’50s. The young Alejandro defies his authoritarian father and leaves his family to join a bohemian commune of artists and poets. In this colorful and surreal world, he discovers love, death, sex, and, above all, the liberating power of poetry.

For Jodorowsky, poetry is not a literary activity but an act of psychomagic, a force capable of tearing through the veil of reality. His cinematic style—baroque, Felliniesque, and carnivalesque—is the direct expression of this philosophy. In Endless Poetry, the world is not simply described by poetry but is literally transformed by it. It is an exuberant and vital work that celebrates art as the highest form of rebellion and self-creation.

Dead Man (1995)

William Blake, a timid accountant from Cleveland, travels to the frontier town of Machine for a new job. After a series of unfortunate events, he finds himself wounded and on the run, accused of murder. He is rescued by a Native American named Nobody, who, due to an incredible homonymy, mistakes him for the great English visionary poet William Blake. Thus begins a spiritual journey towards death.

Jim Jarmusch deconstructs the western genre to create a philosophical and hypnotic “acid western.” The film is a powerful allegory, an initiatory journey in which the mystical and anti-industrial poetry of William Blake becomes the key to reading the violence and brutality of the West. The protagonist, an accountant, a symbol of capitalist rationality, must die to be reborn as a poet and cross the “bridge of mirrors” to the world of the spirit. Robby Müller’s black-and-white photography and Neil Young’s score contribute to creating a unique atmosphere, a cinematic poem about death, transcendence, and a critique of modern civilization.

The Lost Poet

Drama, by Fabio Del Greco, Italy, 2024.

Dante Mezzadri wants to see an old friend, nicknamed the Iguana, whom he has lost sight of for many years, and who has managed to turn their shared youthful passion for poetry into a job, becoming a famous writer and poet. The man escapes from his bourgeois life and his wife to live homeless on the Roman coast, printing and trying to sell his poetry collections. At night he sleeps in a park of old carnival floats, inside a papier-mâché tank, and waits for the opportunity to meet his old friend, who however never shows up for appointments in the places they frequented when they were young, now in ruins. Dante's poetry books do not interest anyone and to support himself he is forced to "change product": he starts selling the infamous "cannibal pill" on behalf of young drug dealers, a new drug that sells like hot cakes and causes sensory and consumerist ecstasy. However, he realizes that this powerful drug is very dangerous for those who take it, he comes into conflict with his ethical conscience and throws all the pills into the sea. However, the dealers want to collect their money.

Shot over a period of 2 years, the film is a reflection on the cultural and artistic rubble of the society in which the protagonist lives, in an increasingly mechanized, consumerist and arid world. Dante Mezzadri is yet another human being who has renounced his inspiration and his creativity, but unlike many he is not willing to give his life to a system that distances him from his true identity. The physical world around him, however, seems constructed in such a way that it seems impossible to escape from this "invisible cage". The enthusiasm of the people he meets is ignited only by sensory gratification, by unreal visions of personal affirmation and success, by "metaverses" that offer an escape into an illusory and destructive reality. The poet's house on the coast, where he met with his friends as a young man, is just a pile of abandoned rubble. What happened to all those who wanted to become poets and ended up becoming something else? Are there internal forces with which that house can be "rebuilt"?

LANGUAGE: Italian

SUBTITLES: English, Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

Barfly (1987)

Written by the poet Charles Bukowski, the film is a semi-autobiographical portrait of his life as a “barfly.” Henry Chinaski, Bukowski’s alter ego played by an unrecognizable Mickey Rourke, spends his days between drinking binges, brawls, and writing poems and stories. His routine is shaken by his encounter with Wanda, another alcoholic, and with Tully, a wealthy editor who wants to publish his writings.

Directed by Barbet Schroeder, Barfly is an unfiltered immersion into the world of “dirty realism.” Poetry here has nothing lofty or academic about it; it is born from the street, from the smell of alcohol, from desperation, and from an indomitable desire to live by one’s own rules. Bukowski’s screenplay is the film’s beating heart: sparse, sharp dialogue, steeped in black humor and desperate lucidity. It is a film that finds a raw and moving beauty in life on the margins, celebrating the dignity of the downtrodden.

Poetry (Si, 2010)

Mija, an elegant woman in her sixties, lives in a small provincial town with her teenage grandson. To fill her days, she enrolls in a poetry class, just as she discovers she is in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Her search for beauty and inspiration brutally collides with a terrible truth: her grandson is involved in a crime that led to the suicide of a classmate.

Lee Chang-dong’s masterpiece is a profound and heartbreaking meditation on the ultimate meaning of poetry. Mija’s quest to write a single, perfect poem becomes an ethical journey. How can one write about the beauty of a flower when one is aware of the horror of the world? The film explores with infinite delicacy the conflict between aesthetics and morality, between the desire to find the right words and the need to face an unbearable reality. In the end, poetry will not be an escape, but the only tool to look pain in the face and give it form.

Part III: The Image as Verse – The Cinema of Pure Poetry

This section is dedicated to the most radical works, to those films that abandon traditional narrative structure to become poetry themselves. Here, cinema pushes its own language to the limits, asking the viewer not to follow a plot, but to inhabit a state of mind, to immerse themselves in a sensory and intellectual experience, just as one would with a lyrical composition.

The Color of Pomegranates (1969)

A portrait of the 18th-century Armenian poet Sayat-Nova, realized not through a conventional biography, but through a series of tableaux vivants (living pictures). The film evokes the stages of the poet’s life—childhood, love, retreat to a monastery, death—using a purely visual, symbolic, and ritualistic language, inspired by Armenian iconography.

Sergei Parajanov’s work is perhaps the most extreme and sublime example of cinema as poetry. The director does not narrate but visualizes the poet’s inner universe, transforming his verses into images of bewildering and hieratic beauty. Devoid of dialogue and traditional camera movements, the film asks the viewer to abandon their perceptual habits and to “read” the images as if they were metaphors, allegories, ideograms. It is a unique cinematic experience, a total work of art that fuses painting, theater, music, and cinema into an unforgettable visual poem.

Nostalghia (1983)

Andrei Gorchakov, a Russian poet, is in Italy researching the life of an 18th-century composer. Accompanied by an interpreter, he wanders through the Tuscan countryside, but his physical journey is overwhelmed by an inner one. He is consumed by a deep and painful nostalgia for his homeland, a feeling that isolates him from the world and brings him closer to a local madman, Domenico, who entrusts him with a spiritual mission.

Andrei Tarkovsky does not film nostalgia, but the substance of which it is made: time. With his concept of “sculpting in time,” the director creates a cinema that moves to the rhythm of the soul’s breath. His very long takes, the dreamlike images that blend the Italian present in soft colors with the Russian past in black and white, do not serve to advance a plot but to immerse the viewer in a state of mind. Nostalghia is a cinematic poem about exile, lost faith, and the impossibility of bridging the distance between oneself and the world.

Andrei Rublev (1966)

Set in 15th-century Russia, an era of brutal Tartar invasions and internal strife, the film follows the life of the great icon painter Andrei Rublev. More than a biopic, it is a monumental meditation on the role of the artist in society, on the relationship between faith and doubt, on the violence of history, and on the possibility of creating beauty in a world that seems to have forgotten it.

Tarkovsky constructs an epic poem in images. Divided into eight chapters, the film abandons a linear narrative to proceed through tableaus, through emblematic moments. Its raw and majestic black and white paints a tangible and ruthless Middle Ages. For nearly three hours, we witness Rublev’s spiritual crisis, his vow of silence in the face of horror. Only in the finale does the film explode into color to show us his icons, affirming that art is an act of faith, a testimony of transcendence that can only be born from the deepest suffering.

Wings of Desire (1987)

Two angels, Damiel and Cassiel, watch over the city of Berlin, still divided by the Wall. Invisible, they listen to the innermost thoughts of the inhabitants, their fears, their dreams, their loneliness. Damiel, tired of being an eternal spectator, falls in love with a trapeze artist and yearns to become human, to finally be able to touch, taste, feel, and love.

Wim Wenders, in collaboration with the poet Peter Handke, creates an urban symphony, a choral poem on the human condition. The film weaves the inner monologues of Berliners into a single, great stream of consciousness, a collective poetry that captures the soul of a city and an era. The stylistic choice to switch from black and white (the ethereal and melancholic perspective of the angels) to color (the sensory and imperfect experience of human beings) is a cinematic metaphor of extraordinary power, a hymn to the fragile and precious beauty of mortal life.

The Blood of a Poet (Le Sang d’un Poète, 1930)

An artist sees the mouth of one of his drawings come to life. In an attempt to erase it, it transfers to the palm of his hand. Desperate, he dives into a mirror, which becomes a portal to another dimension. He walks through the corridor of a surreal hotel, spying through keyholes at enigmatic and dreamlike scenes. It is a journey into the subconscious, an exploration of the artist’s psyche.

The first cinematic work of the poet and total artist Jean Cocteau, The Blood of a Poet is a film-manifesto of the avant-garde. Cocteau does not tell a story but creates what he himself called “plastic poetry.” Through ingenious cinematic tricks and a boundless imagination, the film explores with dream logic the tormented relationship between the creator and his creation, life and death, reality and dream. It is a fundamental work that paved the way for decades of experimental cinema.

Orpheus (Orphée, 1950)

Orpheus, a famous Parisian poet, becomes obsessed with cryptic poetic messages transmitted by a car radio. These messages come from the Afterlife, sent by a mysterious Princess who is Death herself. When his wife Eurydice dies, Orpheus, driven by love and artistic curiosity, follows her into the realm of the dead by passing through a mirror.

The central chapter of Cocteau’s “Orphic Trilogy,” this film is a sublime and fascinating modernization of the classic myth. Cocteau uses special effects of a brilliant simplicity (film projected in reverse, vats of mercury to simulate liquid mirrors) to create a magical and poetic world. The film is a profound allegory about the figure of the poet, perpetually balanced between the world of the living and that of the dead, between earthly love and the allure of the unknown, in a constant search for an inspiration that could cost him his life.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

A woman returns home, falls asleep in an armchair, and begins a dream. Or perhaps the dream has already begun. In a cyclical and repetitive narrative, the woman splits into doubles, chases a cloaked figure with a mirror for a face, and interacts with everyday objects (a key, a knife, a telephone) that take on a symbolic and threatening value. Reality and dream merge into a psychological labyrinth with no way out.

A seminal work of American avant-garde cinema, directed by Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, this short film is structured like a poetic composition. Its spiral narrative, where each repetition adds a new detail and increases tension, is reminiscent of the form of a villanelle or a sestina. Deren theorized a “vertical” cinema, which does not advance horizontally with a plot but digs deep into a single moment, exploring all its psychological and symbolic ramifications. It is a masterpiece of psychodrama, a journey into the female unconscious.

Pull My Daisy (1959)

In a New York loft, a group of Beat Generation poets (including Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso) awaits a visit from a bishop. Their bohemian anarchy clashes with the bourgeois expectations of their friend’s wife, a railway worker. The chaotic and surreal evening is narrated by the free and improvised voice-over of Jack Kerouac.

A symbol of Beat cinema, this short film directed by Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie is an attempt to translate into images the aesthetic of Kerouac’s “spontaneous prose” and the syncopated rhythm of jazz. Although the improvisation was partly constructed, the film perfectly captures the spirit of an era: the playfulness, the irreverence, the rejection of conventions. Kerouac’s narration, a stream of consciousness that comments, digresses, and sings, is the true poetic soundtrack of an irreplaceable cultural document.

Blue (1993)

For 79 minutes, the screen is entirely and solely filled with a shade of ultramarine blue (International Klein Blue). There are no images, no characters, no action. There is only the color. And a complex soundscape made of voices, music, and noises, in which director Derek Jarman and his collaborators reflect on life, love, illness, and death.

Made when AIDS was making him blind, Blue is the final, radical testament of Derek Jarman. It is a “film without a film,” a work that denies the image to exalt the word and sound. By depriving the viewer of their primary sense, Jarman forces them into an experience of deep listening, to create their own mental images from the poetic and diaristic flow of the narration. It is one of the most courageous and moving explorations of the limits of cinematic language, an audiovisual poem on perception and loss.

Le quattro volte (The Four Times, 2010)

In a small village in Calabria, we follow the cycle of life and the transmigration of a soul through four successive existences. An old shepherd dies, and his soul is reincarnated in a newborn kid. When the kid gets lost, its life continues in a majestic fir tree. The fir tree is then cut down to become charcoal, completing the cycle from the animal, to the vegetable, to the mineral kingdom.

Michelangelo Frammartino directs an almost silent film, a work of contemplative cinema that is a true pastoral poem. With a patient and wonder-filled gaze, the director observes the rhythms of nature and ancient human traditions, finding a deep spiritual connection between all forms of life. Inspired by a Pythagorean belief, the film is a philosophical meditation on the unity of the cosmos, told with a pure, essential, and breathtakingly beautiful cinematic language.

The Turin Horse (A torinói ló, 2011)

In an isolated cottage, battered by an incessant wind, a farmer, his daughter, and their horse live an exhausting and repetitive routine. Their existence is reduced to essential gestures: dressing, drawing water from the well, eating a boiled potato. But one day the horse refuses to move, the well runs dry, the fire goes out. The world, slowly, is ending.

Announced as his final film, the work of Hungarian master Béla Tarr is a cinematic poem about the apocalypse. Shot in just 30 very long takes in a dazzling black and white, the film is an extreme example of “slow cinema.” The obsessive rhythm and repetition of gestures create an atmosphere of metaphysical oppression, an almost physical experience of the end of meaning. It is the visual translation of a Nietzschean abyss, a funeral elegy of a terrible and unforgettable beauty.

The Dead (1987)

Dublin, 1904. During the traditional Epiphany dinner at his elderly aunts’ house, the intellectual Gabriel Conroy experiences an evening of small frustrations and social interactions. But at the end of the party, an old song heard by chance awakens in his wife Gretta the poignant memory of a youthful love, who died for her. This revelation shakes Gabriel to the core, leading him to a universal meditation on life, death, and love.

John Huston’s last, sublime film is an adaptation of absolute fidelity and sensitivity of James Joyce’s eponymous short story. Although it is a narrative film, its power is entirely poetic. The final sequence, in which Gabriel’s voice-over recites Joyce’s final words as snow falls silently all over Ireland, is one of the highest moments in the history of cinema. It is the perfect fusion of literary poetry and cinematic poetry, a melancholic and transcendent epitaph.

The Broken Tower (2011)

A fragmented and unconventional portrait of the life of the American modernist poet Hart Crane. The film explores his genius, his alcoholism, his homosexuality, and his desperate search for a new form of poetic expression, leading to his suicide at the age of 32 by jumping from a ship into the Gulf of Mexico.

Written, directed, and starring James Franco, this independent, low-budget project brings the circle to a close, returning the biopic to the territory of experimental cinema. Franco does not seek a linear narrative but tries to construct a film that has the same complex, lyrical, and at times obscure structure as Crane’s poetry. It is a personal and courageous work, an attempt to use the language of cinema not to explain a poet, but to dialogue with his restless soul and his artistic legacy.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision