What is the Avant-Garde

The avant-garde is an extreme artistic movement, unconventional with respect to the dominant art, society or culture. The avant-garde pushes the limits of what is accepted as status, mainly in the cultural world. The avant-garde is regarded as a trademark of modernism. Numerous artists have aligned themselves with the avant-garde movements and continue to do so, tracing history from Dada through the Situationist and postmodern artists. The avant-garde promotes social reforms not accepted in society or still perceived as utopian. In reality, the avant-garde, with the passage of time, seems only an artistic current that anticipates the times, which fights on the front line to create the new. The power of the arts is undoubtedly the fastest and fastest method for social, political and financial reform.

The term “vanguard” was initially used by the French Army to describe a small reconnaissance group that went ahead. At one point in the mid-19th century, the term was linked to art through the concept that art is a tool of social modification. Right towards the end of the century the avant-garde began to move away from its recognition with leftist social causes to become more aligned with creative and cultural concerns. This pattern toward greater focus on issues has continued to this day. Avant-garde today usually describes groups of authors, artists and intellectuals who give voice to concepts and try creative methods that challenge existing cultural values. The concepts of the avant-garde, particularly if they concern social problems, are generally slowly absorbed by societies. Yesterday’s avant-gardes end up being mainstream in the following decades, producing the environment for the emergence of a new generation of avant-gardes.

Avant-Garde and Tradition

The avant-gardists might share particular merits, which manifest themselves in the non-conformist way of life. Fake mass culture is continually created by copying models from a recently emerged cultural market and the success of some avant-garde techniques. This happens regularly in cinema, where cutting-edge films that the mainstream industry would never have thought of turn out to be blockbusters and are copied and made into commercial products. The whole world of famous streaming TV series is based on this: data analysis and recycling of artistic works that have met the favor of the public, with the degradation of the language to the mass level and a more captivating packaging.

Creative quality has been replaced by sales figures as a stepping stone: a novel, for example, is valued based on whether it becomes a best-seller; music has captured the charts with gold record awards, cinema with Oscars and mainstream film festivals controlled by the political-cultural elite. In this way, the creative independence so dear to the avant-garde was abandoned and sales significantly ended up being the validation of everything. The customer culture now reigns in any art. The co-optation of the avant-garde by world market capitalism, neoliberal economies and what Guy Debord called The Society of the Spectacle (a text critical to the Situationist movement explaining the “autocratic reign of the market economy”), they speculated the possibility of a significant avant-garde today. Paul Mann’s Theory-Death of the Avant-Garde shows how today the avant-garde is wholly embedded in institutional structures.

Numerous sectors of the mainstream culture market have misapplied the term “avant-garde” given that in the 1960s it was primarily used as a marketing tool to advertise industrial music and cinema. It has actually become standard to describe popular rock artists and filmmakers as “avant-garde,” and the word has been stripped of its proper meaning. From the mid-1960s onwards, avant-garde culture ceased to fulfill its previous antagonistic function. Since then it has been flanked by ghosts of the avant-garde on the one hand and a changing mass culture on the other, with which it connects to varying degrees.

The European Cinematic Avant-Gardes of the 1920s

In the 1920s a vast panorama of experimentation of European cinema was born by artists from other artistic disciplines such as Cubism, Dadaism and Surrealism, who made important contributions to the development of the nascent cinematographic art: avant-garde cinema.

Avant-Garde Cinema: Futurism

Futurism was an Italian social and creative movement in the early 20th century. He highlighted dynamism, speed, innovation, youth, violence and things like the automobile, the plane and the commercial city. Its crucial figures were the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla and Luigi Russolo. Italian futurism glorified modernity and, according to its teaching, intended to free Italy from the weight of its past. Crucial Futurist works consisted of Marinetti’s 1909 Manifesto of Futurism, Boccioni’s 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Balla’s painting Abstract Speed + Sound of 1913-1914, and Russolo’s The Art of Noises (1913 ).

Futurism was mostly an Italian phenomenon, parallel movements emerged in Russia, where some Russian futurists would later discover groups of their own; other nations either had few futurists or had movements inspired by futurism. Futurists practiced in every artistic medium: painting, sculpture, ceramics, graphics, advertising, interior decoration, theatre, cinema, textiles, literature, music, architecture and even cooking. To some extent Futurism influenced the art movements Art Deco, Constructivism, Surrealism and Dada, and to a greater extent Precisionism, Rayonism and Vorticism.

Futurism and Cinema

Italian futurism was among the most enthusiastic, going so far as to affirm that the very soul of cinema was futurist: rhythm and abstract forms were to be the protagonists of the new works, leaving the story behind. However, the Futurists made few films and most of them were lost: the Thaïs or Perfidious intrigue (1917) by Anton Giulio Bragaglia are the only surviving futurist films. Their thoughtless ideas served to lay the foundations for subsequent artistic movements.

Avant-garde cinema: Abstractionism

Abstract art uses the visual language of shape, line, and color to develop a structure that could exist with a degree of self-sufficiency from visual references throughout the world.

Western art had indeed been, since the Renaissance in the mid-19th century, underpinned by point-of-view reasoning and the effort to replicate an impression of self-evident truth. By the end of the 19th century many artists wanted to develop a new type of art that included the essential changes taking place in science and innovation. Abstract art, non-figurative art, non-objective art, and non-representational art are all associated terms. They have comparable meanings, though perhaps not similar ones. Abstraction suggests a departure from truth in the representation of images in art. This deviation from the representation can be minor, partial or total.

Even art that strives for verisimilitude to the highest degree can be said to be abstract, at least in theory, since ideal representation is difficult. It can be argued that a work of art that takes liberties, for example by changing the color, is partly abstract. Total abstraction bears no trace of any inspiration to anything identifiable. In geometric abstraction, for example, references to naturalistic entities are unlikely to be discovered. Figurative and metaphorical art often consists of partial abstraction. Both geometric abstraction and lyrical abstraction are often absolutely abstract. Among the very many art movements that embody partial abstraction are for example Fauvism in which color is noticeably and intentionally modified with respect to truth, and Cubism, which modifies real-life entities illustrated.

Abstractionism and Cinema

Abstractionism used avant-garde cinema in an even more extreme way, preferring abstract forms and pure movement. Its founder was the Russian painter Vassilij Kandinsky. Abstract cinema was born in Germany in the same years as expressionism and kammerspiel. The directors created films out of all likelihood of reality, with geometric and abstract shapes that danced rhythmically on the screen. Rhytmus 21 (1921) by Hans Richter was the first.

Movement, time, rhythm and light of this film bring us the research of the German director to the primordial essence of cinema, to its purest and non-industrial form. They were followed by Rythmus 23 (1923), Rythmus 25 (1925). Meanwhile the Swedish Viking Eggeling entered into competition with his German colleague and created Diagonal Symphony , another fundamental work of abstract cinema.

Another abstract avant-garde cinema artist was Walter Ruttmann with the works Lichtspiel Opus I , Lichtspiel Opus II , Ruttmann Opus III , Ruttmann Opus IV , film of lights in motion. He will later abandon abstract cinema to make documentaries, such as Berlin – Symphony for a big city (1926) or Melody of the World (1929), inspired by the films of Dziga Vertov.

Halfway between abstract cinema and Dadaism is the work of Marcel Duchamp Anémic Cinéma (1926): 19 rotating optical discs, 10 composed of geometric figures and nine decorated with meaningless phrases. Duchamp called them rotorilievi.

To help him make this film was the painter and photographer Man Ray who he had created a few years earlier Retour à la raison with the technique of rayography invented by himself: he exposed objects in contact with photographic paper or film to create images without using the camera.

Cubism

Cubism is an early 20th-century avant-garde art movement that reinvented European painting and sculpture and influenced associated movements in music, architecture, and literature. In Cubist artwork, things are evaluated, separated and reassembled in an abstract way: instead of portraying the objects from a single perspective, the artist portrays the subject from a wide range of perspectives to represent the subject in a higher context. Cubism has actually been considered the most important art movement of the 20th century. The term is used extensively in association with a wide range of artwork produced in Paris during the 1010s and 1920s.

The movement was conceived by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque and signed by Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay, Henri Le Fauconnier, Juan Gris and Fernand Léger. One effect that cubism caused was the representation of a three-dimensional type in the last works of Paul Cézanne. A retrospective of Cézanne’s paintings was held at the 1904 Salon d’Automne, existing works were exhibited at the 1905 and 1906 Salon d’Automne, followed by 2 celebratory retrospectives after his death in 1907. In France, similar movements were established to Cubism, consisting of Orphism, Abstract Art and later Purism.

The effect of Cubism was complete and significant. In France and other nations Futurism, Suprematism, Dada, Constructivism, Vorticism, De Stijl and Art Deco established themselves in reaction to Cubism. Early Futurist paintings retain Cubism’s fusion of the past and present, the representation of various visions of the subject, while Constructivism is influenced by Picasso. Other typical elements of these different movements are the faceting or simplification of geometric figures and the association of mechanization and modern life.

Cubism and Cinema

he Cubist movement also immediately became interested in avant-garde cinema. The painter Fernand Léger shot the film in 1924 Ballet mécanique . No plot or story, rhythms of bodies and objects in motion, interested only in rhythm. Cinema moved away from reality and concrete stories. The meaning of these films is in the rhythmic dance of images, sounds and light through the montage.

Dadaism

Dadaism was a European avant-garde art movement in the early 20th century, with early centers in Zurich, Switzerland at the Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916). Dadaism in New York City began in 1915, and after 1920 Dadaism developed in Paris. Dadaist activities lasted until the mid-1920s. Established in response to World War I, the Dada movement included artists who rejected the reasoning and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, revealing an anti-bourgeois outlook in their works. Dada artists revealed their discontent with war, nationalism and violence and maintained political affinities with far-left politics.

Dada’s roots lie in pre-war progressivism. The term anti-art, precursor of Dada, was created by Marcel Duchamp around 1913 to define works that challenge the accepted meanings of art. Cubism and abstract art bear witness to the detachment of movement from the constraints of reality and convention. The work of French poets, Italian Futurists and German Expressionists will influence the Dadaist rejection of the close connection between words and meaning.

In France there was instead the Dadaist movement of Tristan Tzara, with a much more radical and subversive aesthetic and ideas. In Dadaism there was anarchy, nihilism, the search for freedom of expression and the rejection of any meaning or final purpose. Dadaism gave us some masterpieces that aroused attention in the artistic world of the time, including the film by René Clair Entr’acte (1924), a film-interval between two times of a live dance show. Here too we find the rejection of any story, the attempt to stay at the roots of the cinematographic art: the viewer is simply led into the joy of life and of the gaze.

Avant-Garde Cinema: Surrealism

The absolute lack of rules and rejection of conventions, however, led Dadaism to crisis and the movement broke up in 1923. Surrealism was born from its ashes, which found in cinema one of its most powerful means of expression. Andrè Breton , founder of the movement, and all his colleagues were interested in the dream world, in everything that manifests itself in the unconscious and outside the ordinary meanings of the world, in the automatic associations of ideas that occur beyond consciousness, in what happens after the loss of any rationality or thought control.

Surrealism is a cultural movement that was established in Europe in the aftermath of the First World War in which artists illustrated illogical disturbing scenes and strategies to allow the unconscious mind to reveal itself. Its goal was, according to leader André Breton, to “confront the previously inconsistent conditions of dream and reality in an absolute truth, a super-reality”, or surreality. He has produced works in painting, literature, theatre, cinema, photography and other media. Numerous surrealist authors and artists consider their work as an expression of the “pure psychic automatism” of which Breton speaks in the first Surrealist Manifesto.

Breton was specific in his assertion that Surrealism was, above all, an innovative movement. At the time, the motion was related to political causes such as communism and anarchism. He was influenced by the Dada movement of the 10s. The term “Surrealism” comes from Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917. The Surrealist movement was not formally developed until after October 1924, when the Surrealist Manifesto published by the French poet and critic André Breton succeeded in declaring the movement avant-garde. The crucial center of the movement was Paris. From the 1920s onwards, the movement spread throughout the world, influencing the visual arts, literature, cinema and music of numerous nations and languages, together with the political idea and practice, the point of view and to social theory.

Surrealism and Cinema

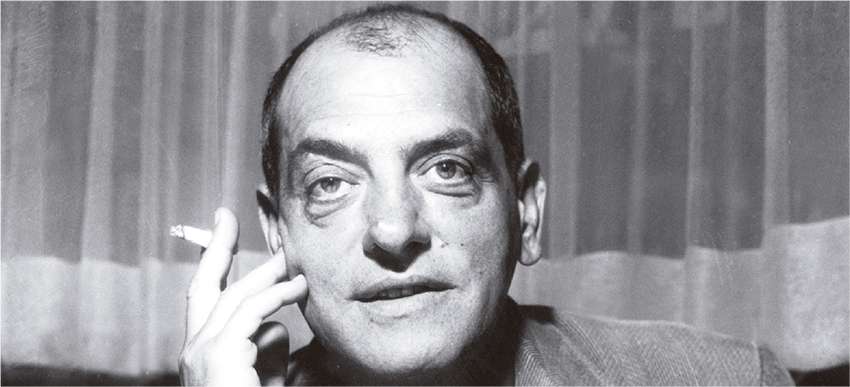

Spanish director Luis Buñuel and painter Salvador Dalì created together in 1928 Un Chien andalou , a film destined to mark a turning point in the history of cinema. A dreamlike and psychoanalytic journey into the most incomprehensible meanders of the human psyche that can have multiple readings and meanings. Surrealism, unlike other previous art movements, creates a new and personal language rather than destroying previous models. Nihilism and anarchy leave room for more traditional narrative codes but used for different purposes. Not to reassure and lead the viewer to a specific destination but to make him lose any reassuring point of reference.

In 1930 Buñuel and Dalì will give life to a new film getting even closer to the classic narration of a story: L’âge d’or . The Spanish director lays the foundations and the first experiments of what will become his obsession throughout his career: the attack on bourgeois institutions such as the church, the army and the state.

Other surrealism films are La Coquille et le Clergyman (1928), the first film by Jean Cocteau (1930), L’Atalante by Jean Vigo, who died in the same year, aged only 29 . His death marked the end of surrealist cinema. The mix of avant-garde style and acceptance of the rules to subvert them or use them in opposite directions made surrealist cinema the most successful and interesting experiment of all the avant-gardes. With a huge influence that lasts until today.

Avant-Garde Films to Watch

Here is a selection of the best avant-garde films to see absolutely: a very prolific genre with a very long filmography that spans the entire history of films.

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Un Chien Andalou is a short film 1929 French silent Luis Buñuel and written by Buñuel and Salvador Dalí. Buñuel’s first film, it was initially shown at the Studio des Ursulines in Paris, but became popular and ran for eight months. A Chien Andalou has no plot in the traditional sense of the word. With a disjointed chronology and time jumps it is a surrealist dream film based on Freudian association. Un Chien Andalou is a seminal work in the category of surrealist cinema.

Man with a Movie Camera, 1929

Man with a Movie Camera is a 1929 Ukrainian Soviet avant-garde documentary, directed by Dziga Vertov, shot by his brother Mikhail Kaufman and edited by Vertov’s wife, Yelizaveta Svilova. Vertov’s film has no actors. From sunrise to sunset the Soviet people show themselves at work and in their free time using the technology of modern life. The film is famous for the variety of cinematic strategies developed by Vertov, such as several direct exposures, fast motion, slow motion, freeze frame, match cuts, dive cuts, split screens, Dutch angles, tracking shots, reversed video shots, stop animation motion and self-reflexive images. You die more avant-garde than that.

The Fall of your home of Usher (1928)

The Fall of your home of Usher (1928) is a short silent horror film adaptation of the 1839 short story “The Fall of your home of Usher” by Edgar Allen Poe. The film was co-directed by James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber and starred Herbert Stern, Hildegarde Watson and Melville Webber. It tells the story of a brother and sister who live in a cursed house. An avant-garde film that lasts only 13 minutes, where the visual component predominates, made up of shots through prisms to develop optical distortion. There is no dialogue in the film, although one scene features letters written in the air across the screen.

The Fall of the House of Usher (1929)

The Fall of your home of Usher is a horror film directed by Jean Epstein, among many films based on the 1839 gothic fiction The Fall of your house of Usher by Edgar Allan Poe. Roderick Usher summons his friend to his old ruined estate in the remote countryside. Usher has been busy painting a picture of his late wife Madeline. When she dies, Usher has her buried in the family crypt, however the public quickly learns that Madeline is not dead and was buried alive. Madeline recovers from her catalepsy, climbs out of her coffin and returns to her astounded husband.

L’Age d’Or (1930)

L’Age d’Or is a 1930 French surrealist satirical film directed by Luis Buñuel about the madness of modernity: everyday life, the hypocrisy of sexual mores of bourgeois society and the value system of the Catholic Church. Much of the story is told with title cards like a silent film. The screenplay of the film is by Buñuel and Salvador Dalí.

About Nice (1930)

It is a short documentary from 1930 directed by Jean Vigo and photographed by Boris Kaufman The film portrays life in Nice, filming individuals in the city, their daily rituals, a carnival and inequalities social. It was Vigo’s first film.

Enthusiasm: The Symphony of Donbas (1931)

Enthusiasm: The Symphony of Donbas is a 1931 avant-garde film directed by the Soviet director Dziga Vertov. The film was the director’s first sound film. The film’s soundtrack consists of factory noises and other sounds; human speech plays only a small role.

The Blood of a Poet (1931)

The Blood of a Poet is an avant-garde film directed by Jean Cocteau, financed by Charles de Noailles and starring Enrique Riveros. It is the first part of the Orphic Trilogy, which continues in Orphée (1950) and concludes in Testament of Orpheus (1960).

Zero for Conduct (1933)

Zéro de conduite is a 1933 French avant-garde film directed by Jean Vigo. It was first shown on April 7, 1933 and was consequently banned in France until November 1945. The film draws heavily on the experiences of the Vigo boarding school to portray a repressive, bureaucratized academic structure in which surreal acts of disobedience take place, showing Vigo’s anarchist vision of youth. The film was not a hit but proved to be enduringly important. François Truffaut was inspired by it for his film The 400 Blows (1959).

The Hearts of Age (1934)

The Hearts of Age is an early film made by Orson Welles. The film is an eight-minute short that he co-directed with friend William Vance in 1934. The film stars Welles’ first wife, Virginia Nicolson, and Welles himself. He made the film while still attending the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois at age 19.

Meshes Of The Afternoon (1943)

A lady (Maya Deren) sees someone in the street on her way back to her house. He goes home and sleeps in a chair. As soon as he falls asleep, he experiences a dream in which he tries to chase a strange hooded figure with a mirror for a face, but is unable to catch it. With each failure, he returns to his house and sees many family items: a bread knife, a telephone, a flower and a phonograph. The woman follows the hooded figure into her bedroom where she sees the figure hiding the knife under a pillow.

Maya Deren is a famous avant-garde film director who was most active in the mid-1940s and is perhaps best remembered for the wildly experimental 1943 short film Meshes of the Afternoon. The film is a dizzyingly bizarre work on the distorted and intangible nature of dreams and has indeed been mentioned as an early inspiration for the work of David Lynch.

Dementia (1955)

Dementia is a horror film American black and white avant-garde John Parker and starring Adrienne Barrett and Bruno Ve Sota. The film, which has no dialogue, follows a girl’s horrific experiences during a night out in Los Angeles. Stylistically, it includes components of horror, noir and expressionist films. Dementia was developed as a short film by writer-director Parker and was based on a dream communicated to him by his secretary, Barrett.

A Story of Water (1958)

A Story of Water is an avant-garde short film directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut in 1958. It tells the story of a lady’s journey to Paris, surrounded by a large flooded place. The film was shot in 2 days and is dedicated to Mack Sennett.

Shadows (1959)

Shadows is a independent film 1959 American John Cassavetes about race relations during the Beat Generation years in New York City. The film stars Ben Carruthers, Lelia Goldoni and Hugh Hurd as 3 black brothers, though only one of them is dark enough to be considered African American. The film was made in 1957 and screened in 1958, however a poor reception prompted Cassavetes to reshoot it in 1959. Film scholars consider Shadows a turning point in American independent cinema. In 1960 the film won the Critics Award at the Venice Film Festival.

Last Year At Marienbad (1961)

It is a French-Italian film from 1961 which represents an exceptional example of the Rive Gauche arthouse movement that began in France in the 1950s. The film is about a man who meets a woman who he is convinced he has met her before, even though she doesn’t remember anything. The film stretches and takes cinematic language to levels rarely seen before, as forgotten dreams and blurred memories merge into a highly subjective story, a unique depiction of the strange nature of dreams and memory.

Dog Star Man (1961-1964)

Dog Star Man is a series of avant-garde short films, all directed by Stan Brakhage. It was released in installments between 1961 and 1964 and comprises an opening and 4 parts. Dog Star Man tells the odyssey of a bearded lumberjack (Brakhage) who climbs a snowy mountain with his dog to cut down a tree. While doing so, he witnesses numerous magical visions with numerous repeating images such as a woman, a child, and nature.

La Jetée (1962)

La Jetée is quite possibly the most popular film of the French Left Bank movement. Shot entirely in black and white, La Jetée is composed of a series of still images that tell a complicated science fiction story. An inmate undergoes training to travel to the past in order to avoid an apocalyptic occasion. Later, he is sent to the future, where he experiences a hyper-advanced civilization that provides him with methods to save the individuals of his era. Meanwhile, he is tortured by an unusual memory of a boy being killed on a dock and, returning to the past, recognizes that this memory was his own murder.

Soy Cuba (1964)

Soy Cuba, otherwise referred to as I Am Cuba, is a 1964 propaganda film by Mikhail Kalotozov, established as a partnership between Cuban filmmakers and the Soviet Union. A series of four short stories, Soy Cuba glorifies Cuba’s 1959 communist transformation and was partly an element of the strengthening ties between Cuba and the USSR at the time. Unusually enough, it was panned by the public when it launched, and may have been completely forgotten had it not been found again years later. The film includes groundbreaking cinematography consisting of long and continuous aerial and underwater shots and was indeed way ahead of its time.

Sleep (1964)

Sleep is a 1964 American avant-garde film by Andy Warhol. Running for 5 hours and 20 minutes, it includes looping video footage of John Giorno, a Warhol fan at the time, sleeping. The film was among Warhol’s first cinematic explorations and was produced as an “anti-film”. Warhol would later extend this strategy to his eight-hour film Empire.

The House Is Black (1967)

The House Is Black is a well-known Iranian short documentary film directed by Fourugh Farrokhzad. The film is a look at life and suffering in a leper hospital and focuses on the human condition. It is interwoven with Farrokhzad’s account of quotations from the Old Testament, the Quran, and his own poetry. The film includes video footage from the Bababaghi Hospice leper hospital. It was the only film he directed before his death in 1967. After making this film he adopted a child from the leper hospital. The film attracted little attention outside of Iran when it was released but is considered a landmark in Iranian cinema and paved the way for the Iranian New Wave.

Faces (1968)

Faces is a 1968 American drama film written and directed by John Cassavetes. In the cast John Marley, Gena Rowlands, Lynn Carlin, Seymour Cassel, Fred Draper and Val Avery. The film won 2 awards at the 29th Venice International Film Festival and got 3 elections at the 41st Academy Awards. The film, shot in cinéma vérité style, illustrates the last marital relationship in crisis of a couple (John Marley and Lynn Carlin). We are introduced to numerous groups and people with whom the couple is confronted after the partner’s unexpected declaration of a desire for divorce.

The Color Of Pomegranates (1969)

The Color of Pomegranates is a 1969 avant-garde film made to chronicle the life and work of the Armenian poet Sayat-nova. The beginning of the film urges the audience not to look for the story in the film’s scenes, rather focusing on the psychological value and poems by which it was vaguely inspired. A long procession of extremely abstract images, it is certainly a difficult film for audiences, especially Western audiences. It is an example of Armenian culture and is a late example of the Soviet avant-garde movement.

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972)

A bourgeois couple, François and Simone Thévenot, accompany François’ colleague, Don Rafael Acosta, the ambassador of the South American country of Miranda, and Simone’s sister, Florence , at the home of the Sénéchals, guests of a dinner. Alice Sénéchal is shocked to see them and says she thought they were coming the next night and didn’t actually cook dinner.

It is a surrealist film by Luis Bunuel of 1972 with a surprising denunciation of bourgeois society. It includes a group of middle class people who are constantly trying to sit down to eat only to be interrupted with weird situations. The film alludes to the warmongering propensities of the bourgeois class and the despair and torment it exerts on the lower classes.

The Holy Mountain (1973)

The Holy Mountain is a 1973 Mexican avant-garde surreal-fantasy film directed, written, produced, co-written, co-edited and starring Alejandro Jodorowsky, who also took part as set designer and dress designer in the film. Following the underground success of Jodorowsky El Topo, well known to both John Lennon and George Harrison, the film was produced by Beatles supervisor Allen Klein of ABKCO Music and Records. Lennon and Yoko Ono pooled the money for the production. It was shown at a number of world film festivals in 1973, including Cannes.

The Phantom of Liberty (1974)

The Phantom of Liberty is a 1974 avant-garde surrealist film by Luis Buñuel, produced by Serge Silberman and starring Adriana Asti, Julien Bertheau and Jean-Claude Brialy. It has a non-linear plot structure that includes several episodes connected only by the movement of characters from one scenario to another and shows Buñuel’s satirical and subversive style integrated with a series of surreal and whimsical events that challenge the public’s preconceived notions about morals social.

Mirror (1975)

Mirror chronicles the ideas, feelings and memories of Aleksei and the world around him as a child, teenager and forty-something. The adult Aleksei is barely glimpsed, however he exists as a commentary in some scenes. The structure of the film is non-chronological, without a traditional plot, and integrates events, dreams, memories and newsreels. The film switches between 3 different time periods: pre-war (1935), wartime (1940s), and post-war (1960s or 1970s).

Mirror Andrei Tarkovsky’s, while not clearly intended as an autobiography, is nonetheless a deeply autobiographical film chronicling the struggles and hardships of those who grew up in the Soviet Union during the 1930s and 1940s. It is a film to be seen several times that cannot be fully understood in one viewing. The cinematography on screen is outstanding. While critics were divided when the film first debuted, the film has acquired a cult following and is considered by some to be one of the best movies ever made.

Eraserhead (1977)

Spencer leaves groceries at her house, which is littered with piles of dirt and dead plants. That night, Spencer reaches X’s house, talking awkwardly to his mother. At the table he is asked to cut up a chicken that X’s dad actually cooked; the chicken shifts and writhes on the plate and gushes blood when cut. After dinner, Spencer is cornered by X’s mom, who tries to kiss him. She informs him that X has had a son. X, however, is not sure if what she has delivered is a baby.

David Lynch may be the best-known modern avant-garde director, and his 1977 work Eraserhead is perhaps the most avant-garde. Meant to be a representation of how stress, anxieties and worries can surface in dreams, Eraserhead is a journey through the worries that can pollute the subconscious.

That Obscure Object of Desire (1977)

That Obscure Object of Desire is a 1977 surrealist comedy-drama directed by Luis Buñuel, based on the film by 1898 The Woman and the Puppet by Pierre Louÿs. It was Buñuel’s last directorial effort before his death in July 1983. Set in Spain and France against the backdrop of a terrorist uprising, the film tells the story through a series of flashbacks of an elderly Frenchman, Mathieu (played by Fernando Rey ), who falls in love with a young Spanish woman, Conchita (played interchangeably by 2 actresses, Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina), who constantly frustrates his sexual and romantic desires.

Wax, Or The Discovery Of Television Among The Bees (1991)

Wax or the Discovery of Television Among the Bees is the first independent feature film by American director and artist David Blair. Blair stars in the film, which also features a cameo from William Burroughs. A mix of ingenious digital animation, exposed video and live action, Wax’s visual language is a representation of the innovations and criticism of politics that still resonate today.

What can be interpreted as a film made to oppose the beginning of the Gulf War, is an unusual avant-garde film. The film centers on a beekeeper who thinks his nest of bees has actually planted a crystal in his head that allows him to speak to the souls of the dead. Cinema’s use of stunning computer-generated effects distort the image on the screen in ways rarely seen in conventional motion pictures.

Film Socialisme (2010)

Film Socialisme is a 2010 French avant-garde film directed by Jean-Luc Godard. The film was first shown in the Un Certain Regard section at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival and launched in France 2 days later. The film consists of 3 acts. The first act, Des choses comme ça (“Things like that”) is set on a cruise ship, with dialogue in several languages. The second act, Notre Europe (“Our Europe”), is set in a petrol station and includes a group of children, a woman and her younger brother, who summon their parents to appear before the “tribunal of their youth”, demanding severe answers on the styles of equality, fraternity and freedom. The last act, Nos humanités (“Our Liberal Arts”), explores 6 famous locations: Egypt, Palestine, Odessa, Greece, Naples and Barcelona.