Comedy is, paradoxically, the most complex and ruthless genre of the seventh art. Much more than drama, it requires perfect timing, surgical writing, and the ability to grasp the contradictions of human nature. Great comic cinema serves not only to escape reality but often to unmask it, using the weapon of irony to reveal truths that would otherwise remain unspeakable.

This guide was created to explore the infinite nuances of humor: from the social satire that made Italian cinema great to the surreal and politically incorrect bite of independent productions, to the elegance of sophisticated comedy. Whether it is liberating laughter or a bitter smile, here you will find the works that have managed to transform entertainment into an art form.

🆕 Best Recent Comedies

A Real Pain (2025)

Two Jewish American cousins, David (Jesse Eisenberg) and Benji (Kieran Culkin), decide to tour Poland to honor their grandmother who survived the Holocaust. David is a neurotic and controlled family man; Benji is a free spirit, charismatic but deeply unstable. What begins as a respectful pilgrimage turns into a clumsy and painfully funny road movie, where historical traumas clash with modern neuroses.

Winner for Best Screenplay at Sundance, this film is the manifesto of modern “Dramedy.” Jesse Eisenberg directs and stars in a work that achieves the miracle of making you laugh in a tragic context (concentration camps) without ever being disrespectful. It is a comedy about grief, family, and how every generation processes loss differently (or not at all).

Nightbitch (2025)

A nameless woman, a former artist and curator, finds herself trapped in domestic routine after the birth of her son, while her husband is always away for work. Exhausted, isolated, and angry, she begins to notice disturbing physical changes: hair growing, teeth sharpening, and an uncontrollable craving for raw meat. Convinced she is turning into a dog, she embraces her new feral nature to rebel against the expectations of the “perfect mother.”

Amy Adams is unleashed in this feminist and surreal horror comedy. Marielle Heller adapts the cult novel creating a biting satire on contemporary motherhood. It is not a classic horror movie, but a grotesque and liberating comedy that screams (and barks) against the loss of identity many women experience. Funny, dirty, and absolutely original.

Anora (2024)

Anora is a young stripper from Brooklyn who thinks she’s living a modern fairy tale when she impulsively marries the spoiled son of a Russian oligarch. The honeymoon ends abruptly when his parents in Russia send their Armenian henchmen to New York to annul the marriage by force. A chaotic and frantic chase ensues across the city, where Anora fights tooth and nail to defend her status as a “wife.”

Winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes 2024, Sean Baker signs a high-energy screwball comedy that recalls the Safdie brothers’ cinema but with more heart. It is a frenetic, loud, and hilarious film that nevertheless hides a bitter critique of social class and the power of money. You laugh a lot, but you desperately root for the protagonist’s dignity in a world that sees her only as a commodity.

The Holdovers (2023)

Christmas, 1970. At a prestigious New England boarding school, a universally hated ancient history teacher (Paul Giamatti), rigid and pompous, is forced to stay on campus during the break to supervise a handful of students who cannot go home. Among them is Angus, a smart but troubled boy. Together with the school’s head cook, who has just lost her son in Vietnam, the three form an unlikely family of outcasts stranded by snow and loneliness.

Alexander Payne creates an “instant classic” that truly feels shot in the 70s. It is a perfect humanist comedy, balancing cynicism and tenderness without ever falling into cheap sentimentality. Paul Giamatti delivers a monumental performance as the misanthrope learning to connect. It is a warm, funny, and melancholic film, written with a grace that is very rare today.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision

Hundreds of Beavers (2024)

In this silent, black-and-white film, an apple cider salesman loses everything to beavers and must become the greatest fur trapper in North America to survive the winter and win the local merchant’s daughter. What follows is an epic and progressively more absurd battle against hundreds of beavers (which are blatantly people in cheap mascot suits), involving traps, chases, and video game logic.

This is the true indie cult hit of the year. Made on a non-existent budget, it is a masterpiece of visual creativity blending Looney Tunes aesthetics, Buster Keaton’s physical comedy, and Super Mario logic. It is pure cinema, made only of action and rapid-fire visual gags (over 1500 shots). A hilarious and anarchic experience that looks like nothing else you’ve seen.

Chasing Butterflies

Comedy, romantic, by Rod Bingaman, United States, 2009.

Nina runs away from home hours before her wedding. In order not to postpone her mother's wedding ceremony, she pretends to be Nina and marries her boyfriend. Soon after they begin their search to find Nina and bring her back: Nina's husband is convinced that she no longer loves him. A fifteen-year-old nerdy boy meets Nina on the street and tries to impress her with his father's Corvette that he sneaked away without having her driver's license. Meanwhile, a rebellious young woman and her boyfriend who has escaped from prison meet the boy and steal his Corvette, sowing panic with a series of thefts as they head to Canada, in search of a better life and money to make their living. love dream. Meanwhile, Nina meets on a bus a man on the run from a failed marriage: a famous local radio broadcaster who has been abandoned by his wife. But the bus will be the target of a robbery by the engaged couple "Natural Born Killers".

Chasing the Butterflies is an action-packed romantic comedy populated by characters destined to cross paths. Love gives them energy or scares them, everyone is on the run in search of a better life or because they don't know how to deal with responsibilities. Everyone refuses to be imprisoned in social conventions even when they themselves have sought them, even when the social convention is that of a marriage to a man you still love. An on the road littered with grotesque situations and hilarious dialogues, often in American slang, made independently, with a very interesting cast.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

Daaaaaalí! (2023)

A young French journalist desperately tries to interview the famous painter Salvador Dalí for a documentary. However, the artist is so egocentric, capricious, and elusive that the interview is constantly postponed, interrupted, or sabotaged by surreal events. The film enters a dreamlike loop where time and space make no sense, and where Dalí is played by five different actors in the same scene, in a tribute to the madness of genius.

Quentin Dupieux, the king of French absurdism, signs a “non-biography” that is a comic maze. He doesn’t try to explain the artist but to replicate his inner world. It is a short comedy (77 minutes), dense with non-sense gags and visually refined. A smart mockery of personality cults and the pretense of “understanding” art. For those who love the humor of Buñuel or Monty Python.

Indie & Arthouse Comedy

Independent comedy does not have to submit to mass market rules: it is free to be strange, grotesque, subtle. Here you will find original stories, unconventional characters, and humor that stems from the imperfections of real life. It is cinema for those who want to laugh, but also think.

👉 BROWSE THE CATALOG: Stream Indie Comedies Now

Black Comedy & Dark Humor

For those who laugh through gritted teeth. Black Comedy finds humor where it shouldn’t be: in death, tragedy, and taboo. It is a genre that dares to challenge good taste and morality to reveal society’s hypocrisies. Perfect for those with a cynical and sharp sense of humor. 👉 GO TO THE LIST: Black Comedy Movies

Dramedy (Comedy-Drama)

Life is never just black or white. The Dramedy is the perfect meeting point between a smile and a tear. Here characters are real and complex, and comic situations arise from discomfort or melancholy. It is the ideal genre for those who want to feel emotion and reflect, while keeping a light and hopeful tone.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Comedy-Drama Movies

Festival in Cannes

Sentimental comedy, by Henry Jaglom, United States, 2001.

Cannes, 1999. Alice, an actress, wants to direct an independent film, and is looking for financiers. She meets Kaz, a talkative businessman, who promises her $ 3 million if she uses Millie, a French star who has passed her youth and no longer finds interesting roles. Alice tells the story of the film to Millie and the actress falls in love with the project. But Rick, a prominent producer working for a large Hollywood studio, needs Millie for a small part in a film due to shoot in the fall, or else he'll lose her star, Tom Hanks. Is Kaz a real producer or is he a charlatan? Rick is actually not as rich as he used to be and he absolutely has to convince Alice to give up Millie in order to close the big project deal with Tom Hanks. Millie is undecided about what to choose: an indie film she loves but with no big money or a small part in the Hollywood movie that pays very well? Meanwhile, a young actress named Blue becomes the star of the festival and Kaz discovers a new love. The wheel of life, and of show business, turns, between feelings, existential budgets and film business. A film shot with great stylistic freedom, like a documentary, during the 1999 edition of the festival, which focuses on the performances of the actors with a spontaneous and fluid improvisation method, inspired by Cassavetes' cinema. A light and moving sentimental comedy, where the conflicts and frailties of the stars of the show business gradually emerge, bringing the important themes of life to the surface.

Food for thought

Working as a cog in a system or for your own vision? Dependence or independence? Both are not completely real: the reality that happens everywhere, in any industry, in any natural event, is interdependence. We are all absolutely interdependent, not only between men, not only between nations, but between trees and humans, between animals and trees, between birds and sun, between moon and oceans, everything is intertwined with everything else. The humanity of the past did not understand this fundamental law, and it created big problems.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

Commedia all’Italiana (The Masters)

It is not just a genre; it is a piece of our country’s history. Between the late 50s and 70s, directors like Monicelli, Risi, and Scola invented a unique way of filmmaking: tackling dramatic themes with humorous tones. You laugh, but the aftertaste is often bitter. It is the cinema of “Monsters,” the fierce satire of the vices and miseries of the average Italian. Essential masterpieces to understand who we are.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Commedia all’Italiana Masterpieces

Romantic Comedy

Love is funny, especially when things go wrong. Forget cheesy stories: the best Rom-Coms are those that recount the embarrassment, misunderstandings, and madness of falling in love with rhythm and intelligence. For those seeking a happy ending but want to have fun along the way.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Romantic Comedies

French Comedy

The elegance of the punchline. Whether it’s classic American Screwball Comedy or brilliant French comedy made of fast dialogue and spicy situations, this is cinema for those seeking cerebral, refined, and never vulgar humor. Here you laugh heartily, but with class.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: French Comedies

Action Comedy

When laughter meets explosions. The perfect genre for a night of pure popcorn entertainment. Buddy movies, clumsy cops, and daring chases: here the pace never drops, and adrenaline mixes with physical gags.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Action Comedy Movies

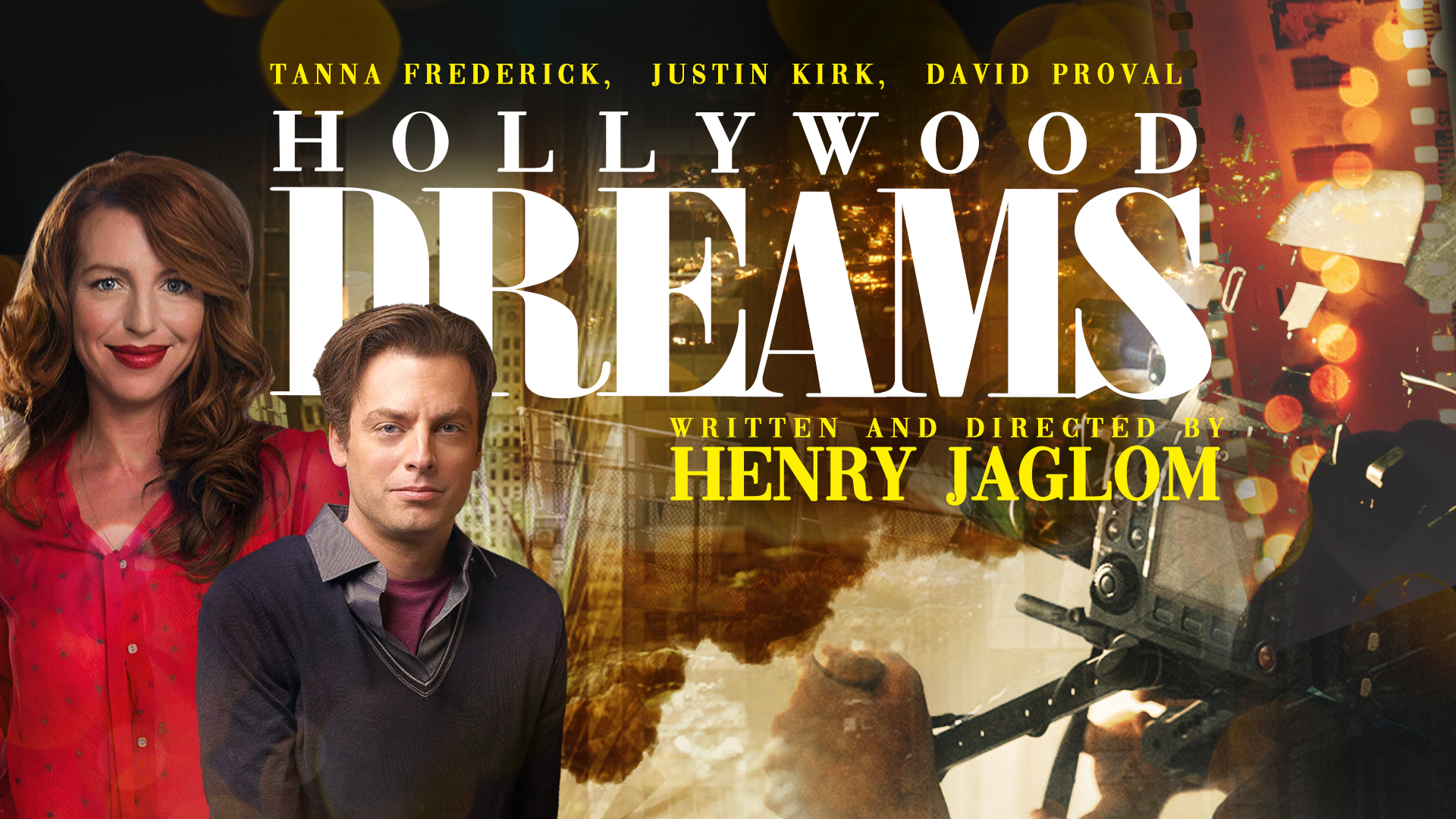

Hollywood Dreams

Comedy, drama, by Henry Jaglom, United States, 2007.

Aspiring actress Margie Chizek seeks stardom in Hollywood. She is rejected by the cinema scene, falls in love, discovers the deceptions behind the world of film advertising and understands her identity better than her. Saved from ruin by a kind producer, Margie manages to enter the world of the rich in Hollywood and falls in love with a young actor, who is building her career by pretending to be gay. The couple will face show business and sexual identity manipulation. Hollywood Dreams engages the audience thanks to the extraordinary performance of Tanna Frederick and her character as a tormented and emotionally unstable actress, a surprising and moving performance. The character of a fragile woman, a prisoner of false myths, at times repellent and bizarre. In the hands of the nonconformist independent director Henry Jaglom the charm of the false illusions of success is told in an exemplary and irresistible way.

The history of cinema is full of films about people making films, which can be interpreted as a universal story: everyone strives for success, recognition and fame in a competitive field. Henry Jaglom's Hollywood Dreams is a subversive film, a satire of an industry based on deception. Inspired by the productive freedom and improvisation of the actors of John Cassavetes' independent cinema, more rigorous and exciting than Henry Jaglom's other films, Hollywood Dreams focuses on a smiling actress who suddenly becomes famous. The director, in his fifteenth film, becomes more melancholy, and takes a journey between cinematic memories and gender identity confusion. The style is always the realistic one, almost a documentary, of other Jaglom films. One of the best known American independent directors in a nostalgic mood, reflecting on the negative aspects of fame and success.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

Comedies of the 20s and 30s

This is the genesis of modern laughter. In the 1920s, comedy was a universal language written with the body: the visual poetry of Chaplin and the stone-faced daredevilry of Buster Keaton defied physics without uttering a single word. The arrival of sound in the 1930s triggered a revolution, birthing the Screwball Comedy. The battleground shifted from stunts to rapid-fire dialogue and wit. It was an era of anarchy and elegance, where the war between the sexes was fought with words at breakneck speed, setting a standard for rhythm that remains unmatched today.

Madame DuBarry (1919)

Madame DuBarry (released in Germany as Passion) is a 1919 German silent historical drama directed by Ernst Lubitsch. This lavish UFA production, filmed at the vast Babelsberg studios, marked the international breakthrough for both its director and its star, Pola Negri. The film chronicles the rise and fall of Jeanne Vaubernier (Negri), a young and ambitious Parisian milliner. Seeking a better life, Jeanne leaves her young love, Armand de Foix, and becomes the mistress of the corrupt nobleman Jean Du Barry, who uses her to gain favor with King Louis XV (Emil Jannings). Jeanne immediately captivates the king, who brings her to Versailles and makes her his official favorite, Madame Du Barry.

The film contrasts Jeanne’s life of luxury and opulence at the court of Versailles with the growing misery and anger of the French populace, which culminates in the Revolution. Madame DuBarry was an enormous critical and commercial success worldwide, praised for Lubitsch’s innovative direction, his use of camera and editing, and Pola Negri’s charismatic and sensual performance. However, its release also generated significant controversy, especially in post-World War I France, where it was viewed as anti-French propaganda for its depiction of a decadent monarchy and a brutal revolution, coming from a recent enemy nation.

The Gold Rush (1925)

The Tramp (Charlie Chaplin), as a lone gold prospector, travels to Alaska during the legendary gold rush. Isolated in a remote cabin, he must face extreme hunger, a ruthless climate, and an unrequited love for the dance hall girl Georgia. Hunger will lead him to surreal acts, such as eating his own shoe and dreaming of the famous “dance of the rolls.”

The Gold Rush represents the moment Charlie Chaplin perfected his alchemical formula, finding the perfect balance between the purest slapstick comedy and heartbreaking pathos. Ironically inspired by a tragic news story about cannibalism among prospectors, Chaplin transforms the horror of desperation into a sublime and unforgettable farce.

The film contains two of the most iconic sequences in the entire history of cinema. The first, the Thanksgiving dinner, where the Tramp cooks and eats his shoe as if it were a gourmet dish, is the manifesto of his art: the ability to transform absolute misery into a meticulous, almost ritualistic, and profoundly moving visual gag.

The second, the famous “dance of the rolls” that the Tramp performs in a dream to entertain the girl he loves, is pure surreal poetry. Both scenes work because Chaplin never just seeks the easy laugh; he seeks empathy. His Tramp is not a comic automaton like many of his contemporaries; he is a complete human being, with desires, fears, and a desperately romantic heart. It is this humanism that distinguishes him from his great rival, Buster Keaton, and that defines the first, fundamental pillar of film comedy.

The General (1926)

Johnnie Gray (Buster Keaton), a Georgia machinist, has two great loves in his life: his fiancée, Annabelle Lee, and his locomotive, “The General.” When the Civil War breaks out, he is rejected by the Confederate army because he is deemed more useful as an engineer. But when Union spies steal “The General” with Annabelle on board, Johnnie embarks on a solitary and daring chase to recover both.

If Charlie Chaplin was the “poet” of comedy, Buster Keaton was its “architect.” The General is his masterpiece, a feat of comic and narrative engineering that is stunningly modern. Unlike the overt pathos of Chaplin, Keaton, “The Great Stone Face,” never asks for our compassion. His comedy is objective, almost mathematical, based on the surreal interaction between an impassive individual and a chaotic, mechanical universe.

The film is legendary for its “almost perfectly balanced narrative structure.” It is literally a film divided into two mirrored parts: the first half is a chase (Johnnie chasing the stolen train North), the second is the opposite chase (Johnnie fleeing South with the train and the girl, pursued by the Northerners).

The authenticity and scale of the gags are legendary. Keaton used real locomotives and cannons, performing extremely dangerous stunts without body doubles, including the scene where he sits on the coupling rod of the moving engine. The result is a large-scale epic that blends comedy, war film, and adventure. Keaton’s influence is visible in everything from Mad Max: Fury Road to the work of Jackie Chan. With this film, Keaton proved that slapstick could be not only funny, but also epic, breathtaking, and immortal.

Queen Of The Lot

Comedy, drama by Henry Jaglom, United States, 2010.

An electronic ankle bracelet and house arrest aren't enough to stop aspiring actress Maggie Chase (Tanna Frederick) from achieving what she desires: popularity and true love. Maggie is determined to make her way off the action / adventure B-movie list and achieve notable movie fame. With a group of managers wanting to help her make it to the covers of the tabloids, and famed actor Dov Lambert, Maggie's stardom rises. Things get complicated when she on a trip to meet Dov lei's family members Maggie she discovers the world of Hollywood's kings (Kathryn Crosby, Mary Crosby, Peter Bogdanovich, Dennis Christopher and Jack Heller). And that world isn't exactly what she imagined.

In this follow-up to 2006 indie comedy drama 'Hollywood Dreams', enthusiastic and insane actress Margie Chizek (Tanna Frederick) has finally arrived in Hollywood as an actress in a B-movie. Maggie's strategies for greater fame could destroy. his film career when he meets the brother of his beloved Aaron (Noah Wyle), who is the black sheep of the Lambert family of actors, but also seems to be the only one who sees the still unstable Maggie for the person she really is . Writer / director Henry Jaglom has a penchant for developing characters that may not be quite pleasant, but are realistic and show a wide range of feelings. Tanna Frederick plays the role of Maggie with skill and she copes well with susceptibility, charm and addiction as she struggles to find happiness in the fierce world of Hollywood. Jaglom reveals that he has real experience of how the Los Angeles film industry really works and how exactly he takes his toll on the private lives of celebrities. Another of Jaglom's qualities as a screenwriter and director is his ability to get into the drama and love his characters without rhetoric. Queen of the Lot is a fun and intriguing indie film, out of the box. Tanna Frederick once again confirms herself as a passionate, gifted and charming actress.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

City Lights (1931)

Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp falls in love with a blind flower girl, who mistakenly believes he is a millionaire. To help her pay the rent and undergo an operation that could restore her sight, the Tramp embarks on a series of adventures, including a fluctuating friendship with a real alcoholic millionaire and a disastrous boxing match. His pure love drives him to sacrifice everything for her.

Including City Lights in this list is a necessity. It is perhaps the ultimate “independent” film: produced, directed, written, scored, and financed by Chaplin himself, at a time when sound cinema had already taken over. His decision to make a silent film in 1931 was an unprecedented act of artistic defiance. The film is a perfect blend of slapstick comedy and heartbreaking pathos. The final scene, in which the girl, no longer blind, recognizes her benefactor, is one of the most powerful and moving moments in cinema history, the ultimate demonstration of how comedy can reach unparalleled heights of emotional depth.

Tokyo Chorus (1931)

Tokyo Chorus (東京の合唱, Tōkyō no kōrasu) is a 1931 Japanese silent film directed by Yasujirō Ozu. Shot in black and white and set in Tokyo during the Great Depression, the film is an influential work of “shomin-geki” (working-class drama) that blends comedy and social drama. The plot follows Shinji Okajima (Tokihiko Okada), an insurance company employee who is fired after protesting the dismissal of an elderly colleague. Left without a job, Shinji struggles to support his family, which includes his wife Sugako (Emiko Yagumo) and their children, son Chounan (Hideo Sugawara) and daughter Miyoko (Hideko Takamine). The family’s economic hardships worsen when their daughter falls ill, forcing them to sell the wife’s kimonos to pay for medical expenses.

Considered one of the most important films of Ozu’s early period, Tokyo Chorus marks a significant transition from his previous slapstick comedies to a deeper, more humanistic analysis of family life and social difficulties. The film is known for its realistic style and minimalist staging, which focuses on evocative details to convey the emotion and resilience of the characters in the face of adversity. With a runtime of approximately 90 minutes and released on August 15, 1931, the film explores enduring themes such as social justice, economic precarity, and the strength of family bonds, showcasing Ozu’s compassion and understanding for people facing life’s challenges.

I Was Born, But… (1932)

I Was Born, But… (original title: 大人の見る絵本 生れてはみたけれど, Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo, 1932) is a Japanese silent film directed by Yasujirō Ozu. Considered one of his early masterpieces, the film is a satirical “shomin-geki” (working-class drama) comedy. The plot centers on young brothers Keiji (Hideo Sugawara) and Ryoichi (Tomio Aoki), who move with their parents to a new Tokyo suburb. The boys try to establish themselves as leaders of the local gang of kids, but their idealized vision of their father (played by Tatsuo Saitō), an office employee, is shattered. While watching home movies, they discover their father acting the fool and humiliating himself to please his wealthy and powerful boss, sparking deep shame in his sons.

The film’s central conflict, in which the father remains alive throughout, concerns disillusionment and the loss of innocence. The boys, shocked by their father’s submissiveness, go on a hunger strike, refusing to accept the complex hierarchies and compromises of the adult world. Ozu explores themes such as social hierarchy, the gap between the world of children and that of adults, and the pressures of “salaryman” life in pre-war Japan with sensitivity and humor. The film is based on an original story by Ozu and was a great critical success in its home country, winning the prestigious Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film.

Duck Soup (1933)

The imaginary state of Freedonia is bankrupt. The wealthy Mrs. Teasdale agrees to finance the country only if the government is entrusted to the incompetent and insolent Rufus T. Firefly (Groucho Marx). Firefly takes over as president and declares war on the neighboring nation of Sylvania over a futile pretext. Meanwhile, spies Chicolini (Chico) and Pinky (Harpo) try to sabotage his plans, leading to total political and military chaos.

While Chaplin feared the arrival of sound, the Marx Brothers wielded it as a weapon of mass destruction. Duck Soup is the purest act of comic terrorism in film history. It is their “liberating scream” against society, a frontal and anarchic assault on logic, social conventions, diplomacy, institutions, and common sense.

The genius of the Marxes lies in their ability to dismantle language. The comedy is not just in the situations, but in the systematic abuse of the word: Groucho’s relentless puns and non-sequiturs, Chico’s literal and absurd malapropisms, and Harpo’s surreal and chaotic muteness, which responds to verbal logic with pure physical action.

Sazen Tange and the Pot Worth a Million Ryo

Comedy, drama, historical, by Sadao Yamanaka, Japan, 1935.

A man gives an old cooking pot to his brother, not realizing that there is a treasure map inside. His sister-in-law sells the pot to a junk dealer, who in turn sells it to a boy named Yasu. A colorful cast of characters are looking for this vase, and when the boy runs away after being scolded by Ogino, everyone chases after him.

There are only three surviving works directed in the short but very rich artistic life by Sadao Yamanaka, who died not even thirty years old in Manchuria in 1938. Among these is The Million Ryo Pot, where the young directorial talent confronts an iconic character of the jidaigeki, Tange Sazen, a one-eyed and one-armed swordsman. In taking an apparently canonical story head-on, Yamanaka opts for a completely personal look, both in the use of parody and in the staging in which long shots and the fixed camera reign in spite of the close-ups that usually crowded the films of the saga. Japanese director Akira Kurosawa cited this film as one of his 100 favorite films. Many Japanese critics and directors consider it the best Japanese film of all time.

LANGUAGE: Japanese language

SUBTITLES: English, Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

It Happened One Night (1934)

Spoiled and stubborn heiress Ellie Andrews (Claudette Colbert) flees her authoritarian father’s yacht to reunite with a pilot husband the family disapproves of. On the night bus to New York, she meets Peter Warne (Clark Gable), a cynical, recently fired journalist. He recognizes her and offers a deal: he will help her on her journey in exchange for an exclusive on her runaway story.

It Happened One Night is not just a film; it is a “landmark film,” an event that changed Hollywood history. It was the project that transformed Columbia Pictures from a B-studio into a major player. It was the first film to win the “Big Five” (the five major Oscars: Best Picture, Director, Screenplay, Actor, Actress), a feat that only two other films (and no other comedy) have managed to equal.

Its greatest historical importance, however, is having invented a genre: the screwball comedy. Frank Capra’s film establishes all the tropes of the genre that would dominate the following decade: the “battle of the sexes,” the class conflict between the spoiled heiress and the cynical but principled common man, the fast and witty dialogue, and a chaotic journey that leads the protagonists to fall in love.

Modern Times (1936)

The Tramp (Chaplin) is an alienated worker in a modern factory, so absorbed by the rhythm of the assembly line that he is literally swallowed by the gears. After a nervous breakdown, he is arrested multiple times, often by mistake. He teams up with a young orphan (Paulette Goddard), and together they try to survive in an industrialized and inhumane world, crushed by the Great Depression.

Modern Times is Charlie Chaplin’s farewell to an era and to his iconic character. It is a hybrid film, an act of artistic and political defiance. Made almost a decade after the advent of sound, Chaplin stubbornly refuses to let his Tramp speak, using only music, sound effects, and mechanized voices (like that of the factory boss barking orders from screens). It is a silent film in a sound era, and this choice is not nostalgia: it is the heart of his thesis.

It is not just a satire on industrialization and worker alienation; it is an artist’s protest against the Hollywood “machine” that was standardizing art. Chaplin, who was also inspired by a conversation with Mahatma Gandhi, saw unbridled industrialization as a threat to humanity, and sound dialogue as a threat to the universality of pantomime.

Bringing Up Baby (1938)

Dr. David Huxley (Cary Grant) is a serious, bumbling, bespectacled paleontologist, one step away from completing the skeleton of a brontosaurus and marrying his rigid assistant. His perfectly ordered life is turned upside down by a chance encounter with Susan Vance (Katharine Hepburn), a “ditzy,” overwhelming, and chaotic heiress who drags him into a series of farcical disasters that include a pet leopard named “Baby.

If It Happened One Night invented the screwball comedy, Howard Hawks‘ Bringing Up Baby is its apotheosis and, perhaps, its purest, most perfect, and most insane form. It is considered “the screwiest of the screwball comedies” and a definitive prototype of the genre. While other screwball films maintained a glimmer of narrative logic, Bringing Up Baby throws itself into total chaos, operating at a frantic pace that gives the viewer no respite.

The film is a textbook of all the genre’s conventions, taken to the extreme: farcical situations, lightning-fast dialogue, slapstick, and the classic dynamic of the “madcap woman chasing the man.” Hepburn, labeled “box office poison” at the time, is an unstoppable cyclone of chaotic energy, and Grant is perfect as the rigid man whose masculinity and rationality are systematically dismantled.

Comedies of the 40s

The 1940s are the decade where comedy became a necessity. While the world was torn apart by war, cinema responded not just with escapism, but with the sharp weapon of political and social satire. This is the golden age of “sophisticated comedy,” where masters like Lubitsch and Sturges used irony to dismantle the hypocrisies of power and the bourgeoisie. Here, laughter becomes more mature, blending romance with an intelligent cynicism that reflects the complexity of the times.

Simon of the desert

Comedy, by Luis Bunuel, Mexico, 1963

Simón, a long-bearded holy man, lives on a column in the middle of the desert, almost in total fasting. People worship him as a Messiah. He performs miracles, undergoes temptations from Satan, who torments him under the guise of a handsome woman. A series of grotesque, surreal, magical and picaresque scenes. The best Bunuel in just 45 minutes.

Food for thought

Those who withdraw from the world to find a spiritual life are doomed to failure. Temptations will follow him, the need to relate to others will not abandon him. Only his ego will be satisfied by a false spirituality. True spirituality is found in everyday life, in the society in which we live, in everyday life, among the people we meet every day.

LANGUAGE: Spanish

SUBTITLES: English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

Tracy Lord (Katharine Hepburn), a cold and haughty Philadelphia socialite, is about to celebrate her second marriage to a social climber. Her charming ex-husband, C.K. Dexter Haven (Cary Grant), shows up on the eve of the wedding. With him are two tabloid journalists, the idealist Macaulay “Mike” Connor (James Stewart) and photographer Liz Imbrie, intent on documenting the event.

The Philadelphia Story is the triumph of sophisticated comedy and the perfect example of the “comedy of remarriage” subgenre. If Bringing Up Baby was pure chaos, this film is a work of surgical precision, built on a razor-sharp script and a cast in a state of grace that saved Katharine Hepburn’s career, who had bought the rights to the play herself.

It is less a screwball and more a comedy of manners, where the stakes are Tracy’s emotional transformation. The film is a sharp exploration of high society, love, and, above all, human fallibility. The narrative goal is to bring Tracy down from her pedestal as a “bronze goddess” and “ice queen” to make her a woman capable of forgiveness and of accepting imperfection, both her own and that of others.

Sullivan’s Travels (1941)

John L. Sullivan (Joel McCrea) is a successful director of light, blockbuster comedies. Tired of being considered frivolous, he decides he wants to make an epic, socially conscious work about human suffering, titled “O Brother, Where Art Thou?”. To find inspiration, he disguises himself as a hobo to experience true poverty. Accompanied by a medical staff and an aspiring actress (Veronica Lake), he discovers that reality is much harsher than he imagined.

Preston Sturges was one of the greatest and most influential comedy auteurs of the classic era, and Sullivan’s Travels is his metalinguistic masterpiece. It is a film about film, an essay on the social responsibility of art, and, ultimately, the most powerful and moving defense of the comedy genre ever made.

The film is a bold, hybrid work, mixing Hollywood satire, slapstick, screwball, and harsh social drama. Sturges subverts expectations by taking his protagonist and the audience on a dark journey, all the way to a prison camp, where Sullivan, beaten and without memory, hits rock bottom.

It is here that the film reveals its thesis. Sullivan, along with the other prisoners, watches a screening of a Mickey Mouse cartoon. In that moment, seeing the inmates forget their misery for a moment to laugh in unison, he understands his mistake. He discovers that “what the downtrodden need most is laughter.” Sullivan’s Travels is a “sermon against sermons” that uses drama to arrive at the revolutionary and profoundly humanist conclusion that making people laugh is not a lesser art; it is a moral duty.

Jour de fete (1949)

Jour de fête (The Holiday) is the first feature film directed by and starring Jacques Tati, released in 1949. A masterpiece of visual comedy, the film is set in a quiet French village during its national holiday celebrations. Tati stars as François, the clumsy and easily distracted local postman. The plot kicks off when François, at the fair’s cinema tent, watches a newsreel about the astonishing efficiency of the United States Postal Service. Determined to modernize his delivery method, François attempts to apply these “American-style” techniques to his humble bicycle route, unleashing a series of surreal gags and chaotic disasters that disrupt the village’s routine.

The film is crucial for defining Tati’s style: a comedy almost devoid of dialogue, built on complex choreography, inventive visual gags, and an acute observation of the conflict between tradition and the encroachment of modern technology. Jour de fête has a unique production history: Tati shot it simultaneously in both black and white and on an experimental color system (Thomsoncolor). Because the color technology proved impossible to print correctly in 1949, it was the black-and-white version (with some hand-colored details added in a 1964 re-release) that was distributed. Only in 1995 was it possible to restore the original color negatives, allowing audiences to see the version Tati had initially envisioned.

Late Springs (1949)

Late Spring (original title: 晩春, Banshun), a 1949 film, is one of the most influential masterpieces by Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu. It marks the beginning of his most celebrated collaboration with actress Setsuko Hara and his regular leading man, Chishū Ryū. The plot centers on Noriko (Hara), a 27-year-old woman who lives happily caring for her widowed father, Professor Shukichi (Ryū), and feels no need to marry. Fearing his daughter is sacrificing her youth for him and will become a “spinster,” Shukichi orchestrates a plan with Noriko’s aunt (Haruko Sugimura). They convince the reluctant Noriko that the father intends to remarry, thereby making her feel she is no longer indispensable and pushing her to accept an arranged marriage.

The film explores with profound sensitivity the themes of personal sacrifice, filial duty, the pressures of tradition, and the melancholy, inevitable dissolution of family ties in the face of change. The heartbreaking and poetic ending shows Noriko accepting the marriage, leaving her father alone after he lied for his daughter’s well-being. The work is based on the short story Father and Daughter (Chichi to Musume) by Kazuo Hirotsu. Late Spring triumphed in Japan, winning the prestigious Kinema Junpo and Mainichi Film Contest awards for Best Film.

The Astronot

Comedy, drama, by Tim Cash, United States, 2018.

Daniel McKovsky is a lost soul wandering the universe. Alone for 30 years he spends his nights staring at the sky with a brass telescope as his only companion. As she looks up, his mind flashes back to that day when as a boy his father hadn't returned from World War II. Having already lost his mother in childbirth, this second stroke sends Daniel down a dark path of isolation deep in the woods of central Oregon. While staring at the moon in the 1950s and 60s, Daniel dreams of becoming an astronaut. The irony though is that he rarely ventures far from his surroundings. The only spark in his life at that moment is the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union to become the first nation to reach the moon. In 1969, a young postal worker named Sandy walks up his driveway with a package for him. It is the antithesis of Daniel; outgoing and vivacious compared to his quiet and reserved nature.

The Astronot is the singular story of a naive and pure character who in some respects recalls the famous Forrest Gump, but unlike him is destined to always be among the losers. From childhood to adulthood, Daniel never loses his enthusiasm for life, even if he has to be content only with picking up metal objects in a wasteland and lives completely alone after losing both parents. The Astronot is a romantic comedy with a vintage aesthetic, set in a remote rural area in the United States. Despite the funny tone, however, life events have a dramatic impact on Daniel's life, almost like a curse, a continuous betrayal of existence that makes fun of a fragile soul. A funny character who experiences tragic situations and creates a strong empathy with the public.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

Comedies of the 50s

The 1950s are the decade of explosive color and apparent optimism. Yet, beneath the glossy Technicolor surface, masters like Billy Wilder began to corrode the American Dream with humor that was bolder, brasher, and more sexually suggestive. While Hollywood created immortal icons like Marilyn Monroe, comedy in Europe took revolutionary paths: Jacques Tati redefined the geometry of the visual gag, and Italy laid the foundations for the social satire that would become legendary.

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953)

Les vacances de Monsieur Hulot (Mr. Hulot’s Holiday) is a 1953 French comedy directed, co-written by, and starring Jacques Tati. The film introduced audiences to Tati’s iconic, pipe-smoking alter ego, Monsieur Hulot. Arriving at a modest seaside resort for his annual vacation, the polite but hopelessly clumsy Hulot attempts to enjoy his time. The film lacks a traditional plot, instead presenting a series of masterful comedic vignettes. Hulot’s well-meaning actions—from playing tennis to trying to dine quietly—inadvertently disrupt the rigid routines and social pretensions of the other middle-class guests, exposing the absurdity of their behavior.

A landmark of visual and sonic comedy, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday solidifies Tati’s place alongside silent masters like Chaplin and Keaton. Tati crafts intricate sight gags that unfold in meticulously composed wide shots. Dialogue is famously minimized, reduced to an unintelligible background murmur, while the soundtrack is built from exaggerated sound effects (like a perpetually squeaking dining room door) that become punchlines in themselves. A gentle, black-and-white satire on the absurdities of modern leisure and conformity, the film—featuring an iconic score by Alain Romans—is celebrated as one of the greatest and most influential comedies ever made.

Equinox Flowers (1958)

Equinox Flower (彼岸花, Higanbana) is a 1958 Japanese drama, notable for being the first feature film directed by Yasujirō Ozu in color. The film, based on a novel by Ton Satomi (not Ozu), stars Shin Saburi as the protagonist Wataru Hirayama, a Tokyo businessman. The plot centers on the generation gap and the conflict between tradition and modernity: Hirayama, who has always supported freedom of choice for his friends’ children, faces a crisis when his own daughter, Setsuko (Ineko Arima), rejects an arranged marriage and announces she wants to marry a man she has chosen herself (Keiji Sada). The cast also includes Kinuyo Tanaka (as the wife) and Setsuko Hara (as a family friend).

The film explores, with Ozu’s usual subtlety, a conservative father’s difficulty in accepting social change and the autonomy of the new generation. The film was not presented in competition or awarded at the Cannes Film Festival, but it remains a pivotal work for its masterful use of color (Agfacolor) and its profound analysis of family relationships in post-war Japan.

Giants and Toys (1958)

Giants and Toys (巨人と玩具, Kyojin to gangu) is a brazen and frenetic 1958 Japanese satire directed by Yasuzō Masumura. Based on a novel by Takeshi Kaikō, the film stars Hiroshi Kawaguchi, Hitomi Nozoe, and Yûnosuke Itō. The plot is set in the ruthless world of post-war advertising, where three candy companies (World, Giant, and Apollo) are locked in a fierce and absurd marketing war. The ambitious advertising chief for World Caramel, Goda (Itō), and his young protégé, Nishi (Kawaguchi), discover Kyoko (Nozoe), a working-class girl with crooked teeth, and decide to transform her into the mascot for their new campaign.

Dressed in a space suit and armed with a ray gun, Kyoko is catapulted to mindless “idol” fame, while the competition between the companies takes on near-military tones. Masumura uses this premise to launch a caustic, high-energy attack on nascent mass consumerism, media manipulation, and the dehumanization of Japan’s corporate world. With its bold use of color and widescreen, Giants and Toys is considered a foundational film of the Japanese New Wave, praised for its sharp social critique and cynical humor.

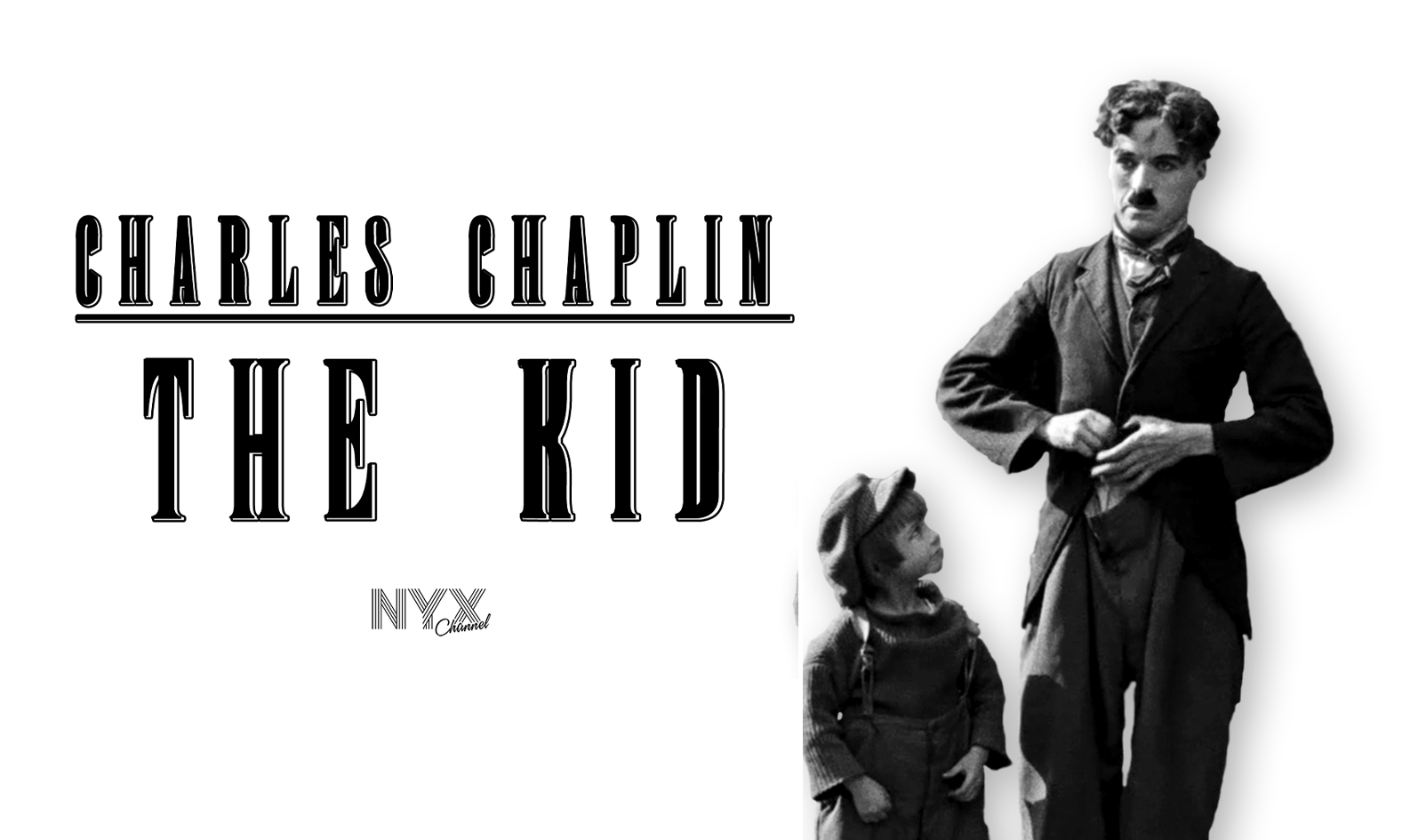

The Kid

By Charlie Chaplin, Comedy, United States, 1921.

Charlie Chaplin writes, produces independently, directs and interprets his first feature film, a masterpiece in the history of cinema which after a century keeps its charm perfectly intact. A poor woman abandons her son in a luxury car hoping that the wealthy owner will take care of the baby. But it will be the tramp Charlot who will find him. Remastered in high definition.

LANGUAGE: english

SUBTITLES: italian

Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958)

A ragtag group of petty thieves from the Roman suburbs, led by the failed boxer Peppe “er pantera” (Vittorio Gassman), plans a seemingly easy heist: robbing the state-run pawn shop. Aided by a retired thief, Dante (Totò), who explains the “science” of the theft in an unforgettable lesson, the gang of incompetents attempts to carry out a plan that turns into a complete and comical disaster.

Mario Monicelli’s I soliti ignoti (original title) is the seminal work that marks the official birth of the Commedia all’italiana (Comedy, Italian Style). It is a fundamental transitional film that takes the aesthetics and settings of Neorealism (the poor suburbs, misery, the struggle for survival) and reinterprets them through the lens of farce, irony, and bitterness.

The film is an explicit and brilliant parody of French film noir, particularly Rififi, a dark film about a perfect heist. But where noir was fatalistic and tragic, Monicelli finds humanity, absurdity, and failure. The film’s genius lies in its ensemble cast (Gassman, Mastroianni, Totò, Claudia Cardinale) and its ability to make these “little hustlers” “likable.” They are not professional criminals, but poor devils trying the heist to make ends meet.

Some Like It Hot (1959)

Chicago, 1929. Two penniless musicians, saxophonist Joe (Tony Curtis) and bassist Jerry (Jack Lemmon), accidentally witness the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. To escape the gangsters who want them dead, they disguise themselves as women (Josephine and Daphne) and join an all-female jazz orchestra traveling to Florida. There, they both fall for the singer and ukulele player, Sugar “Kane” (Marilyn Monroe).

Considered by many critics and polls to be the greatest comedy of all time, Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot is a perfect comic machine. It is the ideal meeting point between the screwball farce of the 1930s and Wilder’s sophisticated cynicism. It is a masterclass in writing, pacing, and tonal management.

The film tackles incredibly audacious and subversive themes for 1959, bypassing the Hays Code with diabolical mastery. It is a comedy about “cross-dressing” that becomes a “problematization of sexual identity.” Wilder and co-writer I.A.L. Diamond explore gender fluidity, homosexuality (the millionaire Osgood courting Daphne/Jerry), and the performative nature of male and female identity.

Comedies of the 60s

The 1960s mark the end of innocence. It is the decade of cultural revolution, and comedy becomes the mirror of this rupture, transforming into a tool of protest. From Kubrick’s apocalyptic black humor ridiculing the Cold War to the definitive explosion of Commedia all’Italiana dissecting the vices of the economic boom. This is an era of total experimentation, where irony becomes a weapon against authority, and old bourgeois values are demolished one laugh at a time.

Zazie in the Metro (1960)

Zazie in the Metro (Zazie dans le métro) is an anarchic and surreal 1960 comedy directed by Louis Malle. The film is a cinematic adaptation of the novel of the same name by Raymond Queneau. The plot follows Zazie (played by the young Catherine Demongeot), a restless and rebellious ten-year-old girl who arrives in Paris from the provinces to stay with her uncle Gabriel (Philippe Noiret), an eccentric man who works as a female impersonator. Zazie’s greatest desire is to ride the Paris Métro, but her plans are immediately frustrated by a major transport strike.

Forced to explore the city above ground, Zazie, along with her uncle and a cast of bizarre characters, gets involved in a series of chaotic and wild adventures. Shot entirely in Paris, the film is celebrated for its slapstick humor, sharp satire, innovative use of editing, and its vibrant portrayal of the French capital. Zazie in the Metro explores themes of rebellion and the discovery of the city through a child’s eyes. The cast also features appearances by Jean-Pierre Cassel and Jeanne Moreau in cameos.

Zero for Conduct

Comedy, by Jean Vigo, France, 1933.

The holidays are over and it's time for the kids to return to the terrible boarding school, run by obtuse and conformist tutors, unable to encourage the growth of any spirit of freedom and creativity. The only thing these austere professors are capable of is assigning a "zero" for conduct. But the boys decide to rebel with the complicity of the new supervisor, Huguet, different from all the others. Thus a real revolution is unleashed. Jean Vigo describes the children's yearning for freedom with audacity and a subversive spirit, with a ruthless critique of the scholastic institution, which closely resembles certain memorable sequences from Fellini's cinema. Perhaps the Italian filmmaker had seen the Vigo film? It seems very, very likely. The film was banned by French censorship and did not have a public screening until 1945.

Food for thought

The conditioning of the family, the school and the mass media are probably the main causes of the existential failure of millions of people. They are unidentified enemies, from which it is difficult to defend oneself, which cause the loss of self-esteem and the creativity necessary to achieve ambitious goals. Social, cultural and religious conditioning are a fundamental theme in the life of every human being, and one of the main topics of the filmographies of masters of cinema such as Fellini, Truffaut, and many others.

LANGUAGE: French

SUBTITLES: English, Spanish, German, Portuguese

Late Autumn (1960)

Late Autumn (秋日和, Akibiyori) is a 1960 Japanese drama film directed by Yasujirō Ozu. Shot in masterful Agfacolor, the film is based on a novel by Ton Satomi and is often considered a thematic “remake” of Ozu’s own Late Spring. The plot centers on Akiko (played by Setsuko Hara), the widow of a deceased friend, and her daughter Ayako (Yoko Tsukasa). On the anniversary of their friend’s death, three middle-aged men (played by Shin Saburi, Chishu Ryu, and Nobuo Nakamura) decide it is time for Ayako to marry. However, their matchmaking attempts become complicated, partly due to their own unresolved affections for the mother, Akiko.

The film delicately explores themes of marriage, filial duty, and loneliness in post-war Japan. The main conflict arises from misunderstandings: Ayako is happy living with her mother and resists the marriage attempts, fearing her mother will be left alone. To free her daughter and allow her to marry (the man she has chosen, played by Keiji Sada), Akiko pretends to be considering remarriage herself. The ending, typical of Ozu’s poetics, is bittersweet: Ayako marries, leaving Akiko to face her solitude. The film also features Mariko Okada and Miyuki Kuwano.

The Apartment (1960)

C.C. “Bud” Baxter (Jack Lemmon) is a mediocre employee at a large New York insurance company. To advance his career, he lends his apartment to his superiors for their extramarital affairs. The situation gets complicated when he discovers that the girl he is secretly in love with, the elevator operator Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine), is the mistress of his boss, the cynical Mr. Sheldrake.

If Some Like It Hot was the pinnacle of farce, The Apartment is Billy Wilder’s humanist masterpiece and the birth of the modern dramedy. It is a romantic comedy that dares to talk about loneliness, corporate corruption, alienation, and attempted suicide. Wilder uses the structure of comedy to deliver a fierce and bittersweet critique of the inhumanity of the corporate world, where everything, including human beings, is a commodity.

The film was considered “licentious” and controversial upon its release, but today it is celebrated for its profound morality. Bud’s transformation, as he ultimately chooses to become a “human being” rather than an “executive,” is one of the most moving in cinema history.

Dr. Strangelove (1964)

A paranoid American general, Jack D. Ripper, convinced that the Soviets are contaminating America’s “precious bodily fluids,” orders an unauthorized nuclear attack on the Soviet Union. In the Pentagon’s “War Room,” President Merkin Muffley (Peter Sellers) and his generals, including the hawkish “Buck” Turgidson, desperately try to stop the plane and the inevitable Russian response: the terrifying “Doomsday” Machine.

Stanley Kubrick takes the greatest fear of his generation—nuclear annihilation—and turns it into the blackest, most grotesque, and most terrifying farce ever conceived. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is the absolute peak of black comedy and political satire. It is a film that dares to laugh at the apocalypse.

Kubrick adopts the horizon of grotesque comedy to highlight the madness of his characters. The Cold War is not depicted as an ideological clash, but as the result of “phallocentric machismo” and bureaucratic ineptitude. The logic of “Mutually Assured Destruction” is taken to its extreme and absurd consequences.

The Producers (1967)

The Producers is a 1967 American satirical comedy film, marking the directorial debut of Mel Brooks. The film stars Zero Mostel, Gene Wilder, Kenneth Mars, and Dick Shawn. The plot follows Max Bialystock (Mostel), a once-famous but now washed-up Broadway producer, and Leo Bloom (Wilder), a timid and neurotic accountant. Bloom casually discovers that a dishonest producer could make more money from a “flop” than a hit by overselling shares in a show destined to fail and keeping the remainder. The two decide to stage the biggest disaster in Broadway history, selecting a musical titled “Springtime for Hitler,” written by a neo-Nazi fanatic (Mars).

Considered a classic of cinematic satire, the film explores themes of greed, corruption, and show business taboos. Its outrageous humor and sharp satire of Nazism and the world of Broadway were groundbreaking for their time. The Producers was a critical success and established Mel Brooks as a comedic auteur. The film won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (Mel Brooks) and received a nomination for Best Supporting Actor (Gene Wilder). It also won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Written American Comedy.

Playtime (1967)

Monsieur Hulot, Jacques Tati’s iconic character, gets lost in a futuristic and dehumanizing Paris, made of glass skyscrapers, labyrinthine offices, and technological gadgets. His path crosses with a group of American tourists, generating a series of meticulously choreographed visual gags that culminate in the anarchic and liberating chaos of a luxury restaurant on its opening night.

Included in this list as a fundamental influence for independent auteurs like Wes Anderson, Playtime is a revolution in visual comedy. Tati abandons traditional narrative and a single protagonist to create an epic urban symphony. The real protagonist is “Tativille,” the modernist and sterile city that the director had specially built for the film. Humor is not delivered through jokes or a single character, but through a complex choreography of small incidents and misunderstandings that occur simultaneously in the enormous 70mm format. Playtime is a satirical and visionary critique of modern architecture and the alienation it produces, a work that demands an active viewer, ready to get lost in its infinite details.

Take the Money and Run (1969)

It is a 1969 film written, directed and performed by Woody Allen. It is a surreal comedy that follows the life of Virgil Starkwell, a clumsy and bumbling criminal who tries in vain to carry out robberies. The film uses an omniscient narrator to poke fun at Virgil’s life and failures, and is known for its visual humor and experimental narrative. Take the Money and Run” is considered one of Allen’s early blockbuster films and has had a lasting impact on popular culture. The plot follows the life of Virgil Starkwell, played by Woody Allen, from childhood to adulthood, focusing on his criminal career.

Virgil is a clumsy and clumsy petty thief who tries to pull off bank robberies and other places, but always gets caught by the authorities. Despite being a criminal, Virgil is portrayed as a comical and hapless character whose actions always lead to unpredictable and amusing consequences. Throughout the film, the character marries twice, is in and out of prison, and finds himself embroiled in increasingly bizarre situations. The narrative is supported by an omniscient narrator who comments and jokes about Virgil’s life, and the film also has some experimental elements, such as the use of black and white screens to represent the actions of the character.

Comedies of the 70s

This is the decade of absolute freedom and neurotic intellectualism. While Woody Allen transforms psychoanalysis into comic art, redefining the romantic comedy, Monty Python dismantles the very logic of humor with their anarchic surrealism. It is an era with no remaining taboos: Mel Brooks’ irreverent parody and social grotesque become powerful tools to exorcise the anxieties of a society in crisis. The laughter of the 70s is cerebral, unpredictable, and magnificently incorrect.

Le Distrait (1970)

Le Distrait (English: The Distracted One) is a 1970 French comedy marking the directorial debut of comic actor Pierre Richard. The film stars Richard himself, Bernard Blier, Marie-Christine Barrault, and Maria Pacôme. The plot centers on Pierre Malaquet (Richard), a young man who is hopelessly distracted and dreamy. His overbearing mother, Glycia (Pacôme), gets him a job at a large Parisian advertising agency run by Mr. Guiton (Blier). Hired into the creative department, Pierre unleashes chaos with his clumsiness and his surreal, literal-minded advertising ideas (like the famous “Klan” toothpaste campaign), infuriating the executives while charming his colleague Lisa Gastier (Barrault).

Shot in color, the film is a sharp satire of the 1970s advertising world and consumerism. Le Distrait is essential for establishing Pierre Richard’s iconic screen persona: the naive, poetic individual whose distraction acts as an inadvertent critique of the absurdity of modern life. Before becoming an international star paired with Gérard Depardieu, Richard defined his unique humor here, a blend of slapstick and tenderness that cemented the film as a classic of French comedy.

Bananas (1971)

Bananas is a 1971 satirical and surreal comedy film, written, directed by, and starring Woody Allen. The film follows the adventures of Fielding Mellish (Allen), a neurotic and awkward product tester from New York. Infatuated with the political activist Nancy (Louise Lasser), Mellish clumsily tries to impress her. After she breaks up with him for not being enough of a “leader,” he suffers an existential crisis and travels to the fictional Latin American republic of San Marcos. There, through a series of chaotic events, he gets involved in a revolution and, much to his own surprise, finds himself becoming its leader.

The film, one of Allen’s early works, is a sequence of paradoxical gags satirizing international politics, “banana republic” dictatorships, and revolutionary movements. The main plot serves as a pretext for a series of absurd comedic scenes, including a farcical trial where Mellish is accused of treason and a famous “Wide World of Sports”-style broadcast commentating on both the dictator’s assassination and Mellish’s wedding night. The eccentric humor and sharp social critique are characteristic of the more slapstick phase of Allen’s filmography.

Harold and Maude (1971)

Harold and Maude (1971) is an influential American black comedy-drama directed by Hal Ashby, based on a screenplay Colin Higgins wrote as his master’s thesis. The film stars Bud Cort as Harold Chasen, a wealthy young man obsessed with death, who expresses his alienation by staging elaborate fake suicides to shock his indifferent mother (Vivian Pickles) and by attending strangers’ funerals. At one funeral, he meets Maude (Ruth Gordon), an eccentric 79-year-old who celebrates life with anarchic joy. The two form a deep, romantic bond that defies all social conventions.

Although met with a lukewarm box office response upon its release, Harold and Maude—filmed in the San Francisco Bay Area—has since become one of the most celebrated and beloved cult films of all time. Its unique blend of macabre humor, critique of conformity, and celebration of individuality has influenced generations of filmmakers. The performances by Cort and Gordon both earned Golden Globe nominations. The film is inextricably linked to its iconic soundtrack, composed and performed by Cat Stevens, which features signature songs like “If You…”

Blazing Saddles (1974)

To route a new railroad through the town of Rock Ridge, the corrupt attorney Hedley Lamarr decides to empty it. As a final move, he appoints a Black man, Bart (Cleavon Little), as the new sheriff, hoping the citizens’ racism will lead to chaos. Bart, however, turns out to be more clever than expected and, with the help of an alcoholic gunslinger, the “Waco Kid” (Gene Wilder), he organizes the resistance.

Blazing Saddles is parody that becomes social satire. Mel Brooks, one of the masters of American farce, doesn’t just make fun of the stereotypes of the Western genre; he uses them as a Trojan horse to frontally attack the racism, corruption, and hypocrisy of American society.

The film is a bombardment of gags, anachronisms (a Yiddish-speaking Indian, a cameo by Duke Ellington), and nonsense, but beneath the demented surface (like the famous bean scene) lies a sharp critique. Released in 1974, the film pushed the boundaries of what was permissible in a mainstream comedy, using the racial slur so blatantly and repeatedly as to render it absurd and, ultimately, powerless.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975)

King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table embark on a surreal and shoestring-budget quest for the Holy Grail. Their journey leads them to face absurd obstacles: an invincible black knight who continues to fight even after being dismembered, rude French knights who taunt them, the dreaded Knights who say “Ni!”, a killer rabbit, and a castle full of tempting virgins.

If Mel Brooks’s American comedy focused on parodying genres, the British comedy troupe Monty Python focused on parodying logic. Monty Python and the Holy Grail is the manifesto of their absurdist, anti-narrative, and philosophical humor. It is a deconstruction not only of the Arthurian myth, but of the very concept of an “epic film” and “plot.”

Made on a shoestring budget, the film transforms every production limitation into a brilliant insight. No money for horses? The knights mime riding while servants bang coconuts together. This gag is not just funny; it is a metacinematic statement that exposes the artificiality of the staging.

Annie Hall (1977)

Neurotic New York comedian Alvy Singer (Woody Allen) recounts his failed relationship with the eccentric and charming Annie Hall (Diane Keaton). Analyzing their story, from meeting to falling in love to the painful breakup, Alvy speaks directly to the audience, using non-linear flashbacks, animated sequences, and surreal encounters to explore love, identity, and the irrationality of human relationships.

Annie Hall is the film that changed romantic comedy forever, and one of the rare cases where a pure comedy won the Oscar for Best Picture, beating Star Wars. Woody Allen took a tired and predictable genre and smashed it to pieces, reconstructing it in a way that was fragmented, neurotic, intellectual, and painfully honest.

It is a profoundly metacinematic work. Alvy Singer breaks the fourth wall to complain to the audience, pulls Marshall McLuhan from behind a poster to win an argument in a movie line, and uses subtitles to show the characters’ conflicting thoughts while they talk about something else. Allen isn’t telling a love story; he’s analyzing a love story, and in doing so, he exposes the artificiality of the genre itself.

Casotto (1977)

Casotto (1977) is an acclaimed Italian ensemble comedy directed by Sergio Citti, who co-wrote the screenplay with Vincenzo Cerami. The film is set entirely within a single, large public beach cabin (the “casotto”) on the public beach of Ostia during a chaotic August Sunday. Inside this confined space, the stories of a gallery of characters intertwine, representing a microcosm of 1970s Italy. Among them are Teresina (a very young Jodie Foster), who is pregnant and trying to manage the situation with her boyfriend (Michele Placido), two clandestine lovers (Ugo Tognazzi and Clara Algranti) seeking a moment of intimacy, and a grandfather (Paolo Stoppa) with his granddaughters.

The film, which boasts an all-star cast that also includes Gigi Proietti, Franco Citti, Ninetto Davoli, and a cameo by Catherine Deneuve, is a grotesque satire on Italian morality and the impending sexual revolution. Using the claustrophobic location, Citti and Cerami stage the hypocrisies, desires, and frustrations of society. Casotto is considered a classic of the Commedia all’italiana (Italian-style comedy) genre, praised for its freshness and ability to capture contemporary reality, and it won the prestigious David di Donatello Award for Best Screenplay.

Comedies of the 80s

The 80s are the era of hedonism and the “High Concept.” Comedy ceases to be a minor genre and evolves into a spectacular blockbuster, blending with sci-fi and adventure (think Ghostbusters or Back to the Future). Yet, it is also the decade where John Hughes codified the language of modern adolescence, treating teen angst with unprecedented dignity. This is fast, colorful, and self-referential cinema that shaped the pop imagination of entire generations.

Airplane! (1980)

Former fighter pilot Ted Striker (Robert Hays), traumatized by war and with a “drinking problem,” boards a flight to win back his ex, the stewardess Elaine. When the entire crew and half the passengers fall ill from food poisoning, Ted must overcome his fears and land the plane, guided by a bizarre air traffic controller.

Airplane! is the “definitive manifesto of contemporary cinematic parody.” The ZAZ trio of directors (Zucker, Abrahams, Zucker) does not just parody a genre, like Mel Brooks; they perform a “systematic deconstruction” that changed comedy forever. The film is an almost shot-for-shot parody of a forgotten 1970s disaster movie, and this manic fidelity is the source of its genius.

The ZAZ directors revolutionized comic timing. The film is a “continuous and relentless bombardment” of jokes, with a gags-per-minute rate that gives no respite. The comedy is multi-layered: literal puns (“Surely you can’t be serious!” “I am serious. And don’t call me Shirley.”), slapstick, visual nonsense, and cinephile parodies.

This Is Spinal Tap (1984)

Filmmaker Marty Di Bergi (Rob Reiner) follows the fictional British heavy metal band “Spinal Tap” during their disastrous American tour promoting their new album “Smell the Glove.” Between amplifiers that “go to eleven,” comically small Stonehenge sets, drummers who die in bizarre accidents, and their declining popularity, the band faces an existential crisis.

This Is Spinal Tap didn’t just parody the “rockumentary” genre; it practically invented it. While not the first mockumentary in history, it is the film that “established the template” and language that influenced everything that came after, from The Office to Parks and Recreation and What We Do in the Shadows.

Its genius lies in its authenticity. The film is so accurate in capturing the “musical pretensions,” fragile egos, stupidity, and dysfunctional dynamics of rock bands that many famous musicians, upon seeing it, thought it was a real documentary. The humor is not shouted; it is “overheard,” based on largely improvised dialogue that sounds perfectly true.

Ghostbusters (1984)

Three quirky scientists and parapsychologists, Peter Venkman (Bill Murray), Ray Stantz (Dan Aykroyd), and Egon Spengler (Harold Ramis), are kicked out of the university. They decide to go into business for themselves, opening a “ghost removal” service in New York. When a portal to another dimension opens in a Central Park apartment building, the Ghostbusters become the city’s only, and unlikely, hope.

Ghostbusters is a “miraculous” film, a cultural event that left an indelible mark on pop culture. It is the rare example of a high-concept (comedy + horror + special effects) that works perfectly. The film redefined the summer blockbuster, proving that a comedy could have the same epic scale as an action or science fiction film.

Its success is not only due to the state-of-the-art special effects for the time, but to the incredible chemistry of the cast, hailing from the orbit of Saturday Night Live. The film has an “intelligent” and “adult” humor. The script by Aykroyd and Ramis is filled with pseudo-scientific jargon, but it is Bill Murray’s slacker, cynical, and detached attitude as Peter Venkman that provides the perfect counterpoint to the impending apocalypse.

Stranger Than Paradise (1984)

Willie, an apathetic Hungarian immigrant living in New York, has his routine disrupted by the arrival of his sixteen-year-old cousin, Eva. After a reluctant ten-day cohabitation, Willie and his friend Eddie decide to visit her in Cleveland. Their journey, marked by existential boredom and deadpan humor, eventually leads them to a desolate Florida, redefining the concept of the American “paradise.

Stranger Than Paradise is not just a film; it’s a manifesto. With its minimalist aesthetic, grainy black-and-white, and vignette structure separated by fades to black, Jim Jarmusch laid the groundwork for modern American independent cinema. The film is a radical departure from the high-energy comedies of the ’80s, replacing gags with a “dramatic nonchalance” that captures a deep sense of alienation. The comedy arises from the void, from awkward silences, and the characters’ inability to communicate. Jarmusch transforms the American landscape into a desolate, anonymous space, a non-place where the protagonists wander aimlessly. It is the birth of the “slacker” archetype, the philosophical loafer whose apathy is a form of passive resistance against a meaningless world.

Heathers (1988)

Veronica Sawyer is part of the most popular and feared clique at her high school, dominated by three girls named Heather. Tired of their tyranny, Veronica finds a kindred spirit in the rebellious new student, J.D. Their relationship takes a dark turn when a harmless prank escalates into a murder, disguised as a suicide. Soon, eliminating the most obnoxious classmates becomes a macabre and satirical habit.

If John Hughes’ films were the teenage dream of the ’80s, Heathers was its satirical nightmare. Michael Lehmann’s film, based on Daniel Waters’ vitriolic screenplay, is the quintessential dark comedy, a work that fiercely dismantles the clichés of teen cinema. Its stylized and iconic dialogue (“What’s your damage?”) became a generational lexicon, a verbal weapon against the superficiality and cruelty of high school hierarchies. The film mixes comedy and shocking violence, using black humor to critique social conformity, bullying, and the media’s tendency to sensationalize tragedy. Heathers proved that teen comedy could be intelligent, subversive, and dangerously funny.

She’s Gotta Have It (1986)

She’s Gotta Have It is the 1986 debut feature film written, directed, produced, and edited by Spike Lee. Shot in black and white on a limited budget ($175,000), the film centers on Nola Darling (Tracy Camilla Johns), a young, independent artist in Brooklyn. Nola asserts her sexual freedom and refuses monogamy, juggling three very different lovers: Jamie Overstreet (Tommy Redmond Hicks), the stable and protective partner; Greer Childs (John Canada Terrell), a wealthy and arrogant model; and Mars Blackmon (played by Lee himself), a comedic, immature, sneaker-obsessed “B-Boy.

The film explores themes of female empowerment, sexual politics, and African-American identity with an adventurous visual style and unprecedented frankness. She’s Gotta Have It became a surprise commercial success (grossing over $7 million) and a critical phenomenon. It is considered a landmark work that launched Lee’s career and helped usher in a new era for American independent film and the “New Black Cinema” of the 1980s, thanks to its wise, funny, and still-relevant voice.

Mortacci (1989)

Mortacci is a 1989 grotesque ensemble film directed by Sergio Citti, who co-wrote the screenplay with Vincenzo Cerami. Set almost entirely in the cemetery of a small Italian town, the film chronicles the nightly gatherings of the deceased buried there. Waiting to “pass on” completely, the dead are condemned to remain in limbo as long as the last living person who remembers them is still alive. Their nocturnal gossip and squabbles are interrupted by the arrival of Lucillo (Sergio Rubini), a soldier who has returned from Lebanon after being presumed dead by everyone.

Lucillo’s arrival causes chaos not only among the dead but, more importantly, among the living. His greedy fellow townspeople have built a lucrative business of pilgrimages and souvenirs based on his status as a “fallen hero.” His return threatens their enterprise, leading the community to a drastic solution: forcing Lucillo to die “for real” to preserve the fiction. Through this biting satire, Citti explores themes of memory, social hypocrisy, and exploitation. The film, which also features Franco Citti and Maurizio Mattioli, received two David di Donatello Award nominations: Best Original Screenplay (for Citti and Cerami) and Best Supporting Actor (for Sergio Rubini).

Comedies of the 90s

The 90s are the decade of contamination and independence. While Jim Carrey pushes physical comedy to new extremes of elasticity, indie cinema rewrites the rules with the “slacker movie” (think Kevin Smith or Linklater), celebrating the art of doing nothing through brilliant, surreal dialogue. It is an era of contrasts: the romantic comedy reaches its global commercial peak, yet simultaneously, an “incorrect” and gross-out humor explodes, definitively shattering the barriers of good taste.

Clerks (1994)

Dante Hicks is called in to cover a shift at the convenience store where he works on his day off. His day turns into an odyssey of bizarre customers, philosophical discussions about the Death Star in Star Wars, and relationship crises. Next to him, his friend Randal Graves, a clerk at the adjacent video store, elevates laziness and sarcasm to an art form, making Dante’s day even more chaotic and memorable.

Clerks is the manifesto of 1990s independent cinema, a triumph of the “write what you know” ethic. Shot in black and white in the actual store where he worked, with a shoestring budget financed by credit cards, Kevin Smith’s film is a celebration of pop culture and male friendship. Its raw aesthetic is not just an economic necessity but a statement of intent: the focus is entirely on the dialogue. The conversations between Dante and Randal, dense with movie references, obscenities, and existential reflections, are the true engine of the film. Clerks ennobled the everyday, finding deep and universal humor in the monotony of a dead-end job and proving that a great story doesn’t need big resources, but an authentic voice.

Living in Oblivion (1995)

Independent director Nick Reve is trying to shoot his first film, but everything that can go wrong, does go wrong. From egocentric and insecure actors to an incompetent crew, technical problems, and surreal dreams, the production is a continuous disaster. The film is divided into three parts, each exploring the nightmares and frustrations of low-budget filmmaking, blurring the lines between reality, dream, and fiction.

Living in Oblivion is the ultimate satire on independent cinema, a cult movie beloved by anyone who has ever tried to make a film. Its clever structure, which plays with color and black and white to distinguish different levels of reality, is a meta-cinematic commentary on the creative process. Director Tom DiCillo, drawing on his own experiences, creates a hilarious and deeply cynical portrait of the chaos, egos, and passion that fuel low-budget cinema. It is a bitter and funny tribute to all the dreamers who struggle to turn their vision into reality.

Bottle Rocket (1996)

Fresh out of a voluntary stay in a psychiatric hospital, Anthony is “rescued” by his friend Dignan, a hyperactive dreamer with an absurd 75-year plan to become a successful criminal. Along with their unenthusiastic accomplice Bob, they embark on a series of clumsy heists. Their journey takes them to a remote motel, where love and complications will test their friendship and criminal ambitions.

Bottle Rocket is the blueprint for Wes Anderson’s entire cinematic universe. Although visually less refined than his later works, this debut film already contains all the distinctive elements of his style: eccentric and ambitious protagonists who are hopelessly incompetent, a deadpan and melancholic humor, and a deep exploration of broken friendships and dysfunctional families. Dignan’s “75-year plan” is the emblem of Anderson’s poetics, a meticulous and almost childlike attempt to impose order on a chaotic world. The film establishes Anderson’s thematic interest in characters who create their own “slightly heightened reality,” a world where naivety clashes with harsh reality, generating a bittersweet and unmistakable comedy.

Waiting for Guffman (1996)

In the small town of Blaine, Missouri, a group of eccentric amateur actors prepares to stage a musical celebrating the town’s 150th anniversary. Led by the exuberant director Corky St. Clair, their hopes reach fever pitch when word spreads that a major Broadway critic, Mort Guffman, will be at the premiere. The anticipation for his arrival transforms the modest production into an epic struggle for fame.