What truly scares us? Cinema has two answers. There is the horror of spectacle: the ‘jump scare,’ the iconic monster, the blood. The collective imagination is marked by masterpieces that defined the genre. But true terror, the kind that creeps under your skin and doesn’t leave, is something else. It is dread, the anxiety of the unknown, the evil that hides not in the dark, but in our own minds.

This guide is not just a ranking of frights. It is a journey into the abyss. It is a path that unites the great classics that have terrified generations with more radical independent films, where the real horror is psychological, social, and existential. Here are 40 films that don’t just aim to scare, but to disturb.

🆕 The New Faces of Fear: Scariest Recent Horror Movies

The Monkey (2025)

Based on a Stephen King short story, the film follows twin brothers Hal and Bill who find an old mechanical toy monkey with cymbals in their father’s attic. Every time the monkey claps its cymbals, someone close to them dies horribly. The brothers try to discard it, but the curse haunts them into adulthood, forcing them to confront the demonic toy to save their new families.

Osgood Perkins (Longlegs) confirms his status as a master of psychological horror. Produced by James Wan but with a rigorous and vintage visual style, The Monkey is not the classic killer doll movie. It is an investigation into the inevitability of death and family trauma, filmed with formal elegance that makes every appearance of the monkey a moment of pure surreal terror, far from modern jump scare clichés.

Cuckoo (2024)

Seventeen-year-old Gretchen moves with her family to a German alpine resort run by the enigmatic Mr. König. Soon she begins hearing strange noises, women’s screams, and seeing disturbing visions. She discovers the resort hides a eugenics experiment involving a humanoid “cuckoo” species that parasitizes families to reproduce, using sonic screams to disorient victims and manipulate time.

German director Tilman Singer (Luz) creates a weird and hallucinatory horror, full of style and neon colors. It looks like nothing else: a fever dream mixing biological sci-fi and slasher. Hunter Schafer is magnetic as the final girl fighting a threat that defies logic. An instant cult classic for those who love strange and sensory cinema.

Azrael (2024)

In a post-apocalyptic world where the sin of speaking is punished by cutting vocal cords, a community of mute fanatics hunts a young woman, Azrael, to sacrifice her to monstrous creatures living in the woods that feed on flesh and suffering. Azrael manages to break free and begins a silent and bloody war against her former captors and the monsters.

A pure survival horror, told almost entirely without dialogue. Samara Weaving (Ready or Not) confirms herself as the queen of indie horror with an exhausting physical performance. The film is an exercise in visual and sonic tension: words are not needed to convey terror. Brutal, primal, and direct, it is a cinematic experience betting everything on action and the oppressive atmosphere of the forest.

The Front Room (2025)

A young couple expecting their first child is forced, due to financial necessity, to take in the husband’s stepmother, an elderly and devout woman who reveals herself to be much more than just an intrusive in-law. The woman brings with her a fanatical religiosity and manipulative ability that begins to distort the reality of the home, turning the protagonist’s pregnancy into a psychological and physical siege.

The debut of the Eggers brothers (Max and Sam, brothers of Robert Eggers of The Witch) is an A24 psychological horror playing with the deepest domestic fears. Kathryn Hunter (the witch from Macbeth) is terrifying as the stepmother: a grotesque and malignant presence embodying religious fanaticism. It is a film that scares because it is plausible: horror does not come from monsters, but from the passive-aggressive violence consumed within the walls of a home.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision

Longlegs (2024)

FBI agent Lee Harker, gifted with psychic sensitivity, is assigned to the cold case of a Satanic serial killer known as “Longlegs.” The killer never touches his victims: he mentally manipulates fathers into slaughtering their wives and children, leaving behind only coded letters. Lee’s investigation turns into a descent into the occult in Longlegs when she discovers the killer has a personal link to her childhood and the threat is much closer than she thinks.

Directed by Osgood Perkins, Longlegs has been called the scariest film of the decade for its ability to generate constant, suffocating anxiety. Nicolas Cage, unrecognizable under grotesque makeup, creates an unforgettable “boogeyman,” a figure straight out of a childhood nightmare. The film doesn’t use cheap scares but builds an atmosphere of subliminal dread that gets under your skin and never leaves.

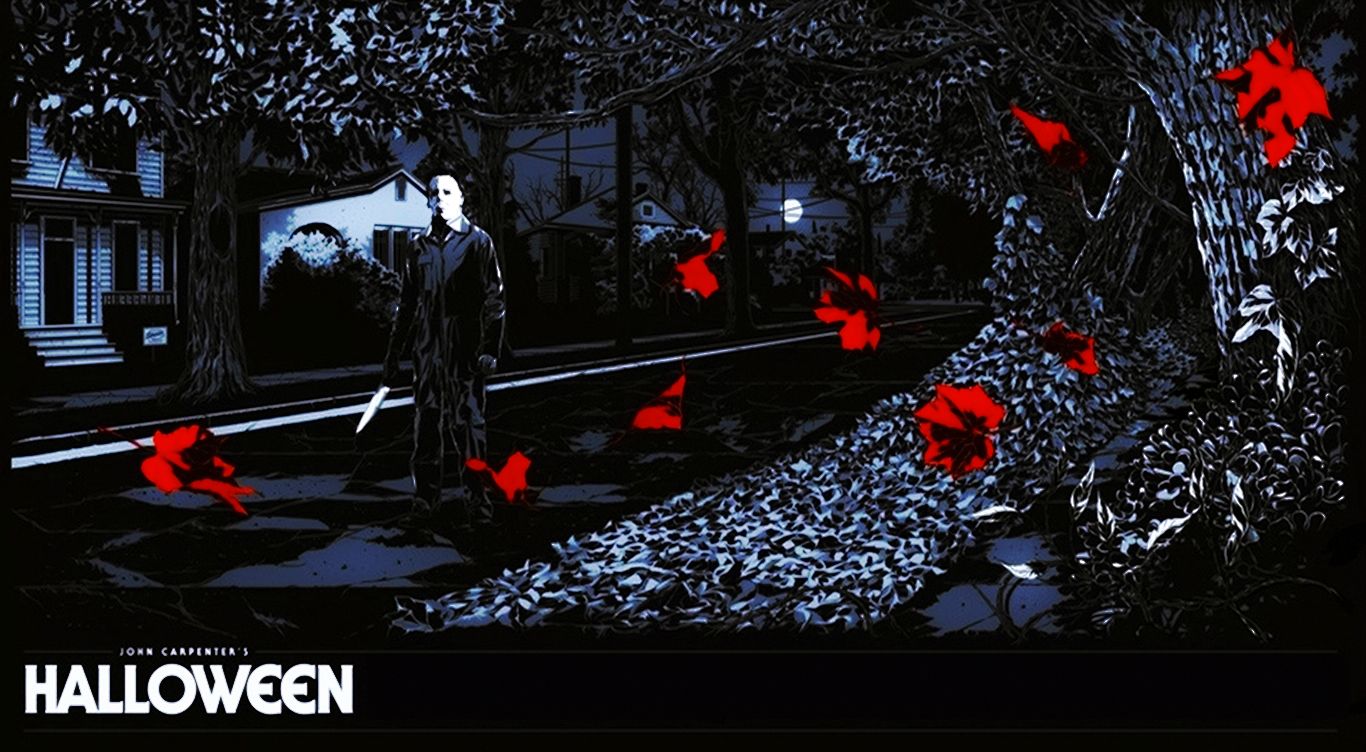

Halloween

Horror, by John Carpenter, United States, 1978.

An independent film shot on a very small budget, it grossed over $ 80 million worldwide at the time. It is the most successful slasher movie and one of the 5 most profitable films in the history of cinema, which has become a cult with countless sequels and reboots. Carpenter describes the remote American province in an extraordinary way and raises the tension for over an hour, without anything happening, with a linear and effective direction, and with hypnotic music created by himself. A brilliant director who manages, with a few simple elements and a small production, to create a horror destined to remain in the worldwide cinematic imagination.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

When Evil Lurks (2023)

In a remote village in Argentina, two brothers discover a neighbor is a “Rotten” (a possessed man) about to give birth to a demon. Attempting to dispose of him far from the village, they make the mistake of violating containment rules, unleashing an epidemic of pure evil. Possession spreads like a virus among inhabitants, animals, and even children, in a world where religion is useless and the only hope is flight.

This Argentine film by Demián Rugna is a masterpiece of cruelty and nihilism. It is scary because it breaks all horror cinema taboos: evil spares no one, not even the innocent, and the violence is sudden, brutal, and shocking. When Evil Lurks strips away every safety net, leaving you in a state of terror and helplessness against an unstoppably force.

Nosferatu (2024)

In 19th-century Germany, young Thomas Hutter is sent to Count Orlok’s castle in the Transylvanian mountains to close a house sale. He doesn’t know that Orlok is an ancient vampire who has become obsessed with Hutter’s wife, Ellen, through a dark psychic bond. While Hutter is trapped in the castle in Nosferatu, Orlok travels toward the city of Wisborg bringing an army of rats and the Black Plague, determined to claim his eternal bride.

Robert Eggers signs the definitive remake of the silent classic, transforming it into a gothic nightmare of rare visual power. Nosferatu is horror that scares through its funereal atmosphere and creature design: Bill Skarsgård plays a pathetic and terrifying monster, light years away from modern sexy vampires. It is a film that smells of earth, disease, and death, capable of evoking ancestral fears.

Oddity (2024)

A year after the brutal murder of her sister Dani in the country house she was renovating, blind psychic Darcy visits her brother-in-law Ted and his new girlfriend. Darcy brings an unsettling gift: a life-sized wooden mannequin from her occult shop. As the night progresses, it becomes clear that the mannequin is not just an object and that Darcy is there to uncover the truth about that night in Oddity, using supernatural terror as a weapon of revenge.

From Ireland comes the revelation horror of the year. Oddity is a clockwork mechanism of tension and smart jump scares. Director Damian McCarthy exploits the protagonist’s blindness and the mannequin’s scary design to create scenes of unbearable suspense. It is a film proving that you can still scare with old tricks (shadows, silence, moving objects) if used with mastery.

What kind of fear are you looking for?

Fear is not the same for everyone. Some seek the visual shock of blood, others the psychological anxiety of the invisible, and some want to be disturbed by surreal visions. To help you find the perfect movie for your sleepless night, we have divided our recommendations by “type of terror.”

Independent Horror

If you are looking for films that don’t follow Hollywood rules, where fear is raw, unpredictable, and often without a happy ending, explore our exclusive selection. On Indiecinema, you will find the horror that dares the most, from classic monsters to new auteur visions.

👉 BROWSE THE CATALOG: Stream Horror Movies Now

Psychological Horror

True terror isn’t outside; it’s inside your head. If you prefer slow tension, paranoia, and movies that leave you with a deep sense of unease rather than making you jump in your seat, this is your list.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Best Psychological Horror Movies

Splatter & Gore Movies

For strong stomachs. If your definition of “scary” includes physical destruction of the body, dismemberment, and visceral realism, here you will find the films that pushed the limits of graphic violence.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Splatter Movies

Ghost Movies

The ancestral fear of the unknown. Haunted houses, invisible presences, and the afterlife trying to enter our world. If you are looking for the classic thrill that makes you sleep with the lights on, here are the masterpieces of the genre.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Ghost Movies

Cult Horror

Some movies have made fear history. From The Exorcist to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, these are the titles that defined the aesthetic of nightmares for generations. If you want to catch up on the basics, start here.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Cult Horror Movies

Body Horror

When the enemy is your own flesh. Mutations, diseases, fusions between man and machine. A disturbing subgenre (made famous by Cronenberg) that explores the fear of losing physical identity.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Body Horror & Mutations

Found Footage (“Real” Terror)

Nothing is scarier than what looks real. From The Blair Witch Project onwards, “found footage” cinema created a new language of terror, based on dirty realism and the absence of cinematic filters.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Best Found Footage Horror

Night of the living dead

Horror, di George Romero, Stati Uniti, 1968.

One of the most profitable independent films of all time, it grossed around 250 times its budget. Inspired like other cult horror films by Richard Matheson's 1954 novel "I Am Legend". Shot as a "guerrilla film" with a cast and crew of friends and family and a budget of just $ 114,000, the film is the forerunner of the inexhaustible "zombie movie" genre.

LANGUAGE: english

The Scariest Horror Movies of all Time

Fear is a universal language that knows no time. Before digital effects, horror was born from shadows, suggestions, and atmospheres so dense they took your breath away. In this section, we travel back into the dark. Here are the masterpieces that taught the world how to be afraid.

Psycho (1960)

Marion Crane, a secretary from Phoenix who has just stolen $40,000 from her employer to marry her indebted boyfriend, flees by car through pouring rain. Tired and nervous, she decides to stop for the night at an isolated motel off the main highway, the Bates Motel. Here she is welcomed by the young and shy manager, Norman Bates, who lives in the large gothic house on the hill with an invalid and domineering mother. What seems like a quiet stop turns into a nightmare when Marion decides to take a shower in Psycho, becoming the victim of one of the most famous murders in cinema history, leaving her sister Lila and lover Sam the task of uncovering the terrifying secret Norman hides in the cellar.

Alfred Hitchcock breaks every rule of classic cinema: he kills off the protagonist (Janet Leigh) after just 40 minutes, shows a toilet (taboo for the time), and introduces the modern figure of the psychotic serial killer, inspired by the real-life case of Ed Gein. Shot in black and white on a TV budget to heighten its rawness, the film is a masterpiece of editing and viewer manipulation. The shower scene, built with 78 cuts and Bernard Herrmann’s screeching score (mimicking stabbing sounds), forever changed the language of fear, proving that horror does not stem from monsters, but from the human mind.

The Innocents (1961)

In Victorian London, Miss Giddens is hired as a governess to care for two angelic orphans, Miles and Flora, who live on the vast country estate of Bly, isolated from the world. Upon arrival, she begins to sense disturbing presences and sees the ghostly figures of the former valet Peter Quint and the previous governess Miss Jessel, both of whom died under scandalous circumstances. Convinced that the ghosts have returned to possess the children’s souls and corrupt their innocence, in The Innocents, Miss Giddens slips into a spiral of obsessive paranoia, where her attempt to “save” the children becomes increasingly aggressive and dangerous.

Based on Henry James’s novella The Turn of the Screw and scripted by Truman Capote, The Innocents is the peak of gothic psychological horror. Jack Clayton creates an ambiguous and terrifying film that never clarifies whether the ghosts are real or the product of the protagonist’s sexual repression. The innovative use of Cinemascope (with blurred edges to create unease), pioneering electronic sound design, and Deborah Kerr’s neurotic performance make it an elegant and deeply disturbing work that influenced all subsequent ghost cinema, from The Others to The Haunting of Hill House.

Black Sabbath (1963)

Introduced by the legendary Boris Karloff, Black Sabbath presents three different nightmares. In “The Telephone,” a woman alone at home is terrorized by a series of threatening calls from an ex-lover she believed dead, building a crescendo of erotic tension. In “The Wurdalak,” set in 19th-century Russia, a noble traveler discovers a family cursed by a form of vampirism that attacks only loved ones. Finally, in “The Drop of Water,” a nurse makes the fatal mistake of stealing a ring from the finger of a dead medium, only to be haunted by the woman’s ghost and the obsessive sound of dripping water.

Mario Bava signs one of the absolute masterpieces of anthology horror, a perfect compendium of his visual genius. Bava experiments with three subgenres: psychological giallo, classic gothic, and supernatural horror, unified by an expressionist use of color (green, purple, and red lights) that creates a dreamlike and suffocating atmosphere. The episode “The Drop of Water” is considered one of the scariest moments in cinema history for its ability to generate pure terror with minimal means, influencing directors from Tarantino to Guillermo del Toro.

Nosferatu

When a young real estate agent, Thomas Hutter, goes to the castle to close a deal, Orlok is attracted by his blood and decides to follow him to his hometown. The arrival of the count causes a series of mysterious deaths and spreads panic among the inhabitants.

Murnau, through evocative images and disturbing atmospheres, creates a work that goes far beyond the simple adaptation of Stoker's novel. The film explores universal themes such as the fear of death, isolation and the loss of humanity. The production of Nosferatu was characterized by some legal difficulties due to the copyright of Bram Stoker's novel. Despite this, Murnau and his crew managed to make a film of great visual impact. The choice of Max Schreck to play Count Orlok was ingenious. His cadaverous appearance and his unnatural movements have made the character of Orlok one of the iconic monsters in the history of cinema. Over the years, Nosferatu has become a cult film, influencing generations of filmmakers and becoming a reference point for the horror genre. The image of Count Orlok, with his elongated nails and sunken eyes, has become an icon of horror cinema.

The Demon (1963)

In an archaic village in Basilicata, young peasant Purificata is obsessed with unrequited love for Antonio, who is about to marry another woman. Her hysterical behavior and convulsions convince the superstitious community that the girl is possessed by the devil. Subjected to brutal exorcisms in the church, stoned by villagers, and finally raped by shepherds, Purificata endures a physical and psychological ordeal that transforms her into an outcast, teetering between schizophrenia and real evil influence in The Demon, leading to a tragic epilogue in the convent.

Directed by Brunello Rondi, The Demon (Il demonio) is not a classic supernatural horror, but a powerful neorealist drama investigating the anthropological horror of Southern Italian superstition. Based on the studies of Ernesto de Martino, the film anticipates The Exorcist by ten years (the famous backward “spider walk” originated here), showing a possession that is primarily social and sexual. Daliah Lavi offers an impressive physical performance in a raw and unsettling work mixing the sacred and profane, documenting a rural world where magic is the only possible explanation for pain.

Kill, Baby, Kill (1966)

A coroner is sent to the remote village of Karmingam to perform an autopsy on a girl who died under mysterious circumstances. He immediately clashes with the hostility of the locals, terrified by a local curse linked to the Villa Graps. The doctor discovers that the ghost of a blonde-haired girl, playing with a white ball, appears to those about to die, driving them to suicide. A convinced rationalist, in Kill, Baby, Kill, the man must face the irrational when he starts seeing the girl himself and getting lost in the villa’s labyrinths.

Considered the last great Italian Gothic, Kill, Baby, Kill (Operazione paura) is the triumph of Mario Bava’s dreamlike style. With a shoestring budget, Bava creates a world of acid colors and impossible architecture that defies logic. The image of the ghost girl with the ball became a genre icon, literally cited by Fellini in Toby Dammit. It is a film of pure atmosphere, where fear stems from decadent beauty and the feeling of being trapped in an endless nightmare.

The Devils (1971)

In 17th-century France, the fortified city of Loudun enjoys special autonomy thanks to its governor, the charismatic and libertine priest Urbain Grandier. But Cardinal Richelieu, wanting to tear down the city walls to consolidate the King’s power, exploits the sexual obsession of Sister Jeanne, the hunchbacked and unstable mother superior of the local convent. When Jeanne, rejected by Grandier, accuses him of bewitching her in The Devils, mass hysteria breaks out: the entire convent of nuns begins simulating erotic possessions, providing the Inquisition with a pretext for a show trial, public torture, and the final burning of the priest.

Ken Russell directs the most controversial, blasphemous, and censored film in British cinema history. The Devils is a baroque and screaming work of art that uses historical horror to attack religious fanaticism and political manipulation. Derek Jarman’s white, sterile sets, reminiscent of a futuristic public bathroom, contrast with the Church’s moral filth. Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave offer titanic performances in a film that is a sensory assault of sex, violence, and sacrilege, yet hides a profound defense of individual freedom against power.

The Exorcist (1973)

Regan MacNeil, a sweet and normal twelve-year-old living in Georgetown with her actress mother, begins to manifest violent and inexplicable behaviors: shouting obscenities, displaying superhuman strength, and undergoing grotesque physical mutations. After medical science fails to find a rational cause, the desperate mother turns to Father Karras, a Jesuit psychiatrist losing his faith. Karras, assisted by the elderly and experienced Father Merrin, must face a grueling exorcism against an ancient demonic entity (Pazuzu) using the girl’s body as a battlefield to humiliate and destroy the faith of the two priests in The Exorcist.

William Friedkin treats the supernatural subject with the rigor of a documentary, creating the scariest horror movie of all time. The Exorcist terrifies because it makes evil tangible, physical, and dirty, placing it in a domestic and everyday context. The special effects (the spinning head, the green vomit, the levitation) are still shocking today for their realism. Beyond the scares, it is a profound theological drama about the fragility of innocence and the mystery of faith, which traumatized a generation and redefined the concept of fear in cinema.

Torso (1973)

In Perugia, an art student sees a red and black scarf belonging to a mysterious killer strangling a girl through a window. From that moment, a masked killer begins brutally murdering foreign female students at the university, mutilating their bodies. Four friends decide to hide in an isolated country villa to escape the terror, but they don’t know that in Torso, the killer has followed them and is ready to carry out a final massacre armed with a saw.

Sergio Martino signs the progenitor of the Italian slasher, a film that heavily influenced Friday the 13th. Torso (I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale) mixes the elegance of the giallo with a dose of sadistic violence and morbid eroticism typical of the period. The long final sequence, almost silent, in which the protagonist (Suzy Kendall) tries to survive hidden in the villa while the killer dismembers her friends’ bodies in the next room, is a masterclass in tension that anticipates the mechanics of the American thriller by years.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

Five friends traveling through rural Texas in a van pick up a deranged hitchhiker who cuts himself and threatens them. Scared, they kick him out and look for gas at an old isolated house. It is a fatal mistake: the house belongs to a family of degenerate and cannibalistic former slaughterhouse workers. One by one, the kids end up in the domestic slaughterhouse of Leatherface, a mute giant wearing a mask of human skin who uses a chainsaw and a hammer to “process” his victims, turning their trip into a nightmare of sun, dust, and screams in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Tobe Hooper changed cinema history with an independent film costing very little and shot under extreme conditions. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is pure visceral terror: no plot, no explanation, just sudden madness bursting into normality. Despite its reputation, the film shows very little blood: the fear comes from the frenetic editing, the deafening sound design (the chainsaw noise, Marilyn Burns’ screams), and the atmosphere of decay and rot that seems to ooze from the screen. It is the work that introduced the concept that the “monster” is not supernatural, but your neighbor.

Suspiria (1977)

Suzy Bannion, a young American ballet student, arrives in Freiburg under a torrential downpour to join a prestigious Dance Academy. Upon arrival, she crosses paths with a fleeing student who is later brutally murdered. Once admitted, Suzy realizes the atmosphere in the school is unhealthy: the teachers are rigid and mysterious, strange breathing is heard in the corridors, and a maggot infestation falls from the ceiling. Investigating, she discovers that the building houses a coven of witches led by the powerful “Mater Suspiriorum,” who uses black magic to kill anyone who uncovers their secret in Suspiria.

Dario Argento abandons the giallo for pure fairy-tale horror, creating his visual masterpiece. Suspiria is a total sensory experience: the saturated Technicolor photography (inspired by Disney’s Snow White) and Goblin’s deafening and tribal score create a dreamlike and delirious world. There is no logic, only magic: it is a film made of primary colors, esoteric architecture, and murders choreographed like works of art. A hallucinating journey into the heart of witchcraft that remains unmatched for style and hypnotic power.

Dawn of the Dead (1978)

While the zombie apocalypse causes American society to collapse, four survivors (two SWAT officers and a TV journalist couple) steal a helicopter and seek refuge on the roof of a massive shopping mall in Pennsylvania. Once the interior is cleared of the living dead, the four barricade themselves inside, living for months in the unbridled luxury of the shops, surrounded by everything they could desire. But their consumerist utopia in Dawn of the Dead is threatened by boredom, internal tensions, and finally the arrival of a gang of human raiders who destroy the defenses, letting the zombie horde in for the final banquet.

George A. Romero’s masterpiece is not only the best zombie movie ever but a fierce social satire on consumerism. The zombies wandering the mall out of “memory instinct” are a mirror of American shoppers. With Tom Savini’s revolutionary splatter effects (exploding heads, realistic disembowelments), Dawn of the Dead is an orgy of colorful and cartoonish violence that entertains and provokes thought. It is the work that defined the modern rules of the survival horror genre, mixing action with political critique.

Alien (1979)

The commercial starship Nostromo, returning to Earth with a mining haul, is awakened by the ship’s computer “Mother” to investigate a distress signal from an unknown planet. In Alien, the crew discovers a derelict alien ship containing thousands of eggs. When a parasitic organism attaches itself to a crew member’s face, he is brought aboard, violating quarantine. From that moment, a perfect and indestructible alien predator begins to grow and hunt the crew through the ship’s claustrophobic corridors, leaving Warrant Officer Ellen Ripley as the last line of defense.

Directed by Ridley Scott, this film is a masterpiece of tension that forever fused science fiction with horror. Thanks to the biomechanical and sexualized creature design by artist H.R. Giger, Alien is not just a monster movie, but a Freudian nightmare about penetration and forced male pregnancy. The elegant, slow direction builds an unbearable sense of cosmic isolation, culminating in the famous “chestburster” scene that shocked audiences worldwide.

The Changeling (1980)

John Russell, a successful composer devastated by the death of his wife and daughter in a car accident, moves from New York to a large, isolated mansion in Seattle to find peace and compose music. However, the house is not empty. In The Changeling, Russell begins to hear inexplicable noises, like a ball bouncing down the stairs and glass breaking on its own. He soon discovers that the villa is haunted by the restless spirit of a child murdered decades earlier, seeking justice through him.

Peter Medak directs one of the most elegant and frightening haunted house movies ever made. Without relying on jump scares or exaggerated special effects, the film builds terror through sound and atmosphere. The séance scene and the wheelchair sequence have become legendary for their ability to freeze the blood. George C. Scott delivers an intense and pained performance, anchoring the supernatural horror to a realistic human drama about grief and loneliness.

Inferno (1980)

Rose Elliot, a New York poet, buys an ancient book titled The Three Mothers, written by an alchemist architect, and discovers that her apartment building is built over the home of one of the three most powerful witches in the world, Mater Tenebrarum. In Inferno, Rose disappears mysteriously after venturing into the building’s flooded basement. Her brother Mark, a music student in Rome, flies to New York to find her, getting involved in a series of bizarre murders and discovering that the Three Mothers rule the world through pain and tears.

The second chapter of the trilogy begun with Suspiria, Dario Argento’s film is a visual delirium of pure aesthetics. Abandoning narrative logic almost entirely, Argento creates an alchemical nightmare dominated by primary colors (blue and red) and water. The score by Keith Emerson (of Emerson, Lake & Palmer) replaces Goblin with operatic progressive rock. It is an imperfect but fascinating film, full of unforgettable dreamlike sequences like the underwater room.

Cannibal Holocaust (1980)

A New York anthropologist travels to the Amazon to find four young documentary filmmakers who went missing while trying to film local tribes. He finds only their remains and the film reels. Back in the studio, viewing the raw footage in Cannibal Holocaust, he discovers a chilling truth: the filmmakers were not innocent observers, but sadistic criminals who raped, burned villages, and killed animals to provoke the indigenous tribes and get sensational footage, ending up justly massacred and eaten in revenge.

Ruggero Deodato signs the most controversial and censored film in history, inventing the Found Footage genre decades before The Blair Witch Project. The extreme realism of the scenes (including real animal killings, unfortunately) led the director to court on charges of murdering the actors. Beyond the scandal, it is a powerful and nihilistic film that fiercely criticizes the sensationalism of Western media and our hunger for real violence.

Cannibal Ferox (1981)

Three New Yorkers head to the Amazon to disprove the thesis that cannibalism still exists. Gloria, who is writing a thesis to prove that cannibalism is a racist myth invented by colonialists, clashes with brutal reality when they meet Mike and Joe, two cocaine smugglers fleeing from natives. In Cannibal Ferox, it is revealed that Mike tortured and killed locals to steal emeralds, triggering a ferocious reprisal by the tribe who captures the group and subjects them to medieval torture in the jungle.

Umberto Lenzi responds to Deodato with an even more explicit and cruel film, pushing the limit of gore to the unbearable (castration, hooks in breasts, skinning). Marketed as “The most violent film ever made,” it is a work of pure exploitation lacking the political subtlety of Cannibal Holocaust, but striking for its visual ferocity and unexpected funk soundtrack. A cult classic for lovers of the extreme that marked the end of the Italian cannibal subgenre.

Possession (1981)

Mark returns to West Berlin after a long spy mission to find his wife Anna changed, distant, and hysterical. She demands a divorce but denies having another man. Mark, devastated by jealousy and despair, discovers the truth is much darker: in Possession, Anna is having a secret relationship not with a human, but with a monstrous, tentacled creature she hides in an empty apartment, feeding it the corpses of her lovers to help it evolve into something perfect.

Andrzej Żuławski directs a visceral psychological horror about the disintegration of a marriage. The film is famous for the titanic performance of Isabelle Adjani (awarded at Cannes), who screams and contorts in an act of physical madness in the famous subway scene that has entered cinema history. It is a symbolic and disturbing work about the war of the sexes, political division (the Berlin Wall is always in the background), and the pain that turns us into monsters.

The Evil Dead (1981)

Five college students decide to spend a weekend in an isolated cabin in the Tennessee woods. In the cellar, they find a tape recorder and a book bound in human skin and written in blood, the Necronomicon. Listening to the tape in The Evil Dead, they inadvertently summon Sumerian demons that possess the woods and, one by one, the students themselves. Ash Williams, the reluctant hero, must fight against his friends transformed into deformed and cackling monsters, in a night of splatter and claustrophobic siege.

Sam Raimi’s debut is a miracle of low-budget creativity. With a crew of friends and tons of inventiveness (the “shaky cam” mounted on wooden planks to simulate the demon’s view), Raimi created a pure horror, without irony (which would come in the sequel), that is a sensory assault of blood, screams, and decay. Stephen King called it “the most ferociously original horror film of the year,” launching its myth.

The Beyond (1981)

Liza inherits an old hotel in Louisiana built over one of the seven gates of Hell. During restoration work, a series of fatal accidents begins to strike the workers and the plumber. In The Beyond (…E tu vivrai nel terrore! L’aldilà), Liza and local doctor John discover that the portal was opened due to the murder of a painter in 1927, and now the dead are returning to earth. The film has no happy ending: the protagonists flee into a nightmarish hospital only to find themselves trapped in a surreal and desolate dimension.

Lucio Fulci signs his dreamlike masterpiece, a film where narrative logic is completely replaced by atmosphere and gore. Famous for eye-gouging violence scenes and attacks by tarantulas and zombies, the film is above all a visual poem on death and the inescapability of fate. The ending, set in an abstract, foggy landscape inspired by Flemish painters, is one of the most nihilistic and poetic in the horror genre.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

In Springwood, teenagers begin to die in their sleep, killed by a disfigured man with a striped sweater and a homemade glove with razor blades. Nancy Thompson discovers the monster is Freddy Krueger, a child murderer burned alive by neighborhood parents years earlier, returned as a vengeful spirit. In A Nightmare on Elm Street, Nancy realizes that to survive she must drag Freddy from the dream world into reality, where he is vulnerable, turning her bedroom into a trap full of booby-traps.

Wes Craven revitalizes the slasher by introducing a genius concept: you can’t run because you have to sleep. Freddy Krueger is the only horror monster endowed with a sarcastic and sadistic personality, capable of manipulating dream reality in creative ways. The film masterfully plays on the ambiguity between sleep and wakefulness, creating iconic scenes (the bathtub, the tongue-phone, the bed swallowing Johnny Depp) that terrified a generation.

The Vanishing (Spoorloos) (1988)

During a vacation in France, Rex and Saskia stop at a busy gas station. Saskia goes in to buy drinks and vanishes into thin air. Rex spends the next three years searching for her desperately, plastering the country with flyers, unable to move on with his life without knowing the truth. In The Vanishing, the man who kidnapped her, Raymond Lemorne, a quiet chemistry professor and family man, decides to contact Rex and make him a terrible offer: if he wants to know what happened to Saskia, he must agree to undergo exactly the same fate.

This Dutch thriller by George Sluizer was defined by Stanley Kubrick as “the most terrifying film I’ve ever seen.” There are no monsters or blood, only the banality of evil embodied by a methodical sociopath who wants to test the limits of his own morality. The ending is one of the most shocking, claustrophobic, and perfect in cinema history, a lesson on how human curiosity can be stronger than the instinct for survival.

Ringu (1998)

An urban legend circulates among Japanese teenagers: there is a cursed videotape that, if watched, leads to death within seven days after a ghostly phone call. Journalist Reiko Asakawa, investigating her niece’s death, watches the tape and receives the call. In Ringu, Reiko discovers that the abstract images on the video are the psychic projection of Sadako’s hatred, a girl with paranormal powers thrown into a well years earlier. To save herself and her son, she must solve the mystery and appease the spirit, but she will discover that the curse does not end with pity, but only with viral propagation.

Hideo Nakata launched the “J-Horror” phenomenon worldwide with this film. Based on the fear of technology (TV, the telephone) and the folklore of vengeful ghosts (Yurei), Ringu is a masterpiece of atmospheric tension. The final scene, where Sadako literally crawls out of the TV screen in an unnatural way, became a global icon of terror, proving that a ghost with long hair over its face can be scarier than any CGI monster.

Saw (2004)

Two men, photographer Adam and Dr. Lawrence Gordon, wake up chained to opposite sides of a dilapidated industrial bathroom, with a corpse in a pool of blood between them holding a gun. Through tape recorders found in their pockets, they discover they are pawns in the sadistic game of a serial killer named Jigsaw. The killer doesn’t murder his victims directly but places them in deadly traps from which they can escape only by making extreme physical sacrifices (like sawing off a foot) to prove how much they value their lives. In Saw, Gordon has until six o’clock to kill Adam, or his wife and daughter will die.

James Wan revolutionized modern horror with a low-budget psychological thriller that spawned a billion-dollar franchise. Unlike its sequels, the first film is not simple splatter, but a claustrophobic and moral mystery that forces the viewer to ask uncomfortable ethical questions. With a twist ending that went down in cinema history for its shocking impact, the film defined the aesthetic of “Torture Porn,” while maintaining a tension that is more psychological than graphic.

[REC] (2007)

Reporter Angela Vidal and her cameraman Pablo are filming a night shift at a Barcelona fire station. When a distress call comes in from an old apartment building where an elderly woman is screaming, the crew follows the firefighters inside. As soon as they enter, authorities seal the building from the outside, placing everyone under quarantine without explanation. In [REC], Angela soon discovers she is trapped with an unknown infection that turns residents into rabid, fast-moving beasts, and the only escape route seems to lead to the penthouse, where the origin of the horror hides.

Directed by Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza, this Spanish film is one of the best examples of found-footage horror ever made. The use of the handheld camera is not a gimmick, but a tool to create suffocating realism and a sense of real-time panic. The film is famous for its terrifying finale (filmed with night vision) which reveals the contagion is not viral but demonic in nature, mixing zombies and religious possession in a crescendo of unbearable tension.

Inside (2007)

Sarah, a pregnant photographer recently widowed (she lost her husband in the car accident she caused), spends Christmas Eve alone at home awaiting childbirth. Her night turns into a nightmare when an unknown woman dressed in black knocks at the door, knowing everything about her and demanding to enter. The intruder doesn’t want to steal objects: she wants to rip the baby from her womb with a pair of scissors. Thus begins a home invasion of unheard-of ferocity in Inside, where every household object becomes a weapon and the bathroom turns into a lake of blood.

A spearhead of the “New French Extremity,” this film by Bustillo and Maury is considered one of the most violent and bloody horror movies ever made. It is not a simple slasher, but a nightmare about monstrous motherhood and guilt. The amount of blood shed is surreal and the tension never drops, transforming pregnancy from a symbol of life into an element of pure body horror. A painful physical experience, culminating in a finale of poetic and devastating cruelty.

Lake Mungo (2008)

After sixteen-year-old Alice Palmer drowns in a dam during a trip, her family begins to experience strange phenomena in their home in Ararat, Australia. Her brother installs video cameras and captures images that seem to show Alice’s ghost wandering the hallways. The desperate family turns to a parapsychologist and discovers that Alice was leading a secret double life. But the truth that emerges in Lake Mungo is far more disturbing than a simple haunting: a video found on the girl’s cell phone reveals what Alice really saw on the shores of Lake Mungo days before she died.

This Australian mockumentary is a masterpiece of sadness and existential terror. Unlike the usual frenetic found-footage films, Lake Mungo is slow, melancholic, and terribly realistic in portraying the pain of a broken family. It doesn’t use jump scares but builds a sense of deep anguish that explodes in the final revelation of the cell phone footage: an image of omen and death considered one of the scariest in modern horror cinema for its concept of the inevitability of fate.

Martyrs (2008)

France, 1970s. A young girl named Lucie is found wandering the streets, confused and covered in wounds, after escaping from an unknown place of torture. Years later, Lucie, now an adult but haunted by monstrous visions, bursts into a bourgeois home and slaughters a family she believes to be her tormentors. Her friend Anna rushes to help her but discovers a secret passage leading to an underground laboratory. In Martyrs, Anna becomes the new victim of a philosophical sect seeking to discover the secrets of the afterlife through the systematic torture of young women, aiming to create a “Martyr” who can see what lies beyond death.

Pascal Laugier writes and directs the most philosophical and unbearable film of French extreme horror. The first part is frenetic action horror; the second is a clinical and slow descent into pure suffering. It is not violence for fun, but violence as a tool for metaphysical transcendence. The film divided the world between those who consider it a masterpiece and those who see it as sadistic trash. The enigmatic ending is one of the most powerful and discussed in the genre, leaving the viewer with a question that has no answer.

A Serbian Film (2010)

Miloš, a retired porn star and family man, accepts a well-paid final job from a mysterious art director, Vukmir, to secure a future for his wife and son. He doesn’t know the script. He soon discovers he has been dragged into a “New Serbian Cinema” project involving acts of extreme sexual violence, pedophilia, and necrophilia. Drugged and manipulated, in A Serbian Film, Miloš loses control of his actions, becoming both protagonist and victim of a nightmare that will destroy everything he loves and his own sanity.

Considered the most shocking and controversial film of all time, it has been banned in dozens of countries. Director Srđan Spasojević defended it as a political metaphor for Serbian society (“raped” by the government and war), but the imagery is so extreme (including the infamous “newborn porn” scene) as to make it nearly unwatchable. It is a technically well-made film, with icy cinematography, using shock to scream against the hypocrisy of the civilized world. An indelible traumatic experience.

I Saw the Devil (2010)

When his pregnant fiancée is brutally dismembered by a psychopathic serial killer, secret agent Kim Soo-hyun decides to take justice into his own hands. He tracks down the killer, Kyung-chul, but instead of arresting or killing him immediately, he decides to torture him: he breaks his arm, implants a GPS transmitter, and lets him go, only to find him and torture him again in an endless cycle of hunting. In I Saw the Devil, the line between the monster and the man hunting him vanishes, turning revenge into an act of moral self-destruction.

Kim Jee-woon directs a South Korean thriller that is pure operatic violence. Visually splendid and choreographed like a ballet of blood, the film flips the concept of catharsis: revenge brings no peace, but transforms the hero into a sadist worse than the villain. Choi Min-sik (Oldboy) offers a monstrous performance as the killer who feels no pain or remorse, challenging the hero to descend to his level. A masterpiece of extreme Asian cinema.

The Eyes of My Mother (2016)

In an isolated American farmhouse, young Francisca witnesses the brutal murder of her mother, a former Portuguese eye surgeon, by a passing serial killer. Her father captures the killer and keeps him chained in the barn, allowing Francisca to “play” with him. Growing up in total solitude and desensitized to violence, in The Eyes of My Mother, the girl develops a distorted idea of love and companionship, beginning to kidnap and mutilate people (removing their eyes and vocal cords) to create a “family” that can never leave her.

Nicolas Pesce’s debut is an American gothic horror shot in beautiful, high-contrast black and white. It is a slow, silent, and deeply disturbing film that relies not on blood but on a sick atmosphere and the protagonist’s loneliness. Francisca is not a monster out of malice, but due to unprocessed trauma that has rendered her incapable of distinguishing affection from torture. A work of macabre art reminiscent of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre filtered through the gaze of an arthouse director.

Under the Shadow (2016)

Tehran, 1980s, during the Iran-Iraq War. Shideh, a modern woman banned from resuming her medical studies due to her political past, finds herself alone at home with her daughter Dorsa while her husband is at the front. When an unexploded missile hits the roof of their apartment building, killing a neighbor, Dorsa begins behaving strangely, talking to imaginary friends. Shideh becomes convinced that the missile brought with it a Djinn, a malevolent wind spirit wanting to possess the child. In Under the Shadow, the mother must fight a war on two fronts: against the real bombs falling outside and against the invisible entity inside the house.

Director Babak Anvari uses supernatural horror as a powerful metaphor for the female condition under the post-revolutionary regime and the anxiety of war. The Djinn is not just a ghost; it is the embodiment of fear and repression suffocating women (the veil trying to swallow them). A smart and scary film demonstrating how horror can be a great vehicle for social and historical critique.

Raw (2016)

Justine is a strict vegetarian starting her first year at veterinary school, following in the footsteps of her older sister Alexia. During a brutal hazing week, she is forced to eat a raw rabbit kidney. This act triggers an allergic reaction that soon turns into an insatiable craving for meat, first animal and then human. In Raw, Justine discovers that cannibalism is not a disease, but a terrible female genetic legacy she shares with her sister, leading to a bloody confrontation between family affection and predatory instinct.

Julia Ducournau (future Palme d’Or winner with Titane) debuts with a cannibal coming-of-age story that is already a modern classic. The film uses gore not to disgust, but to tell of sexual awakening, social pressure, and the complex relationship between sisters. Visually elegant and full of pop colors, it is a body horror that manages to be incredibly tender and revolting at the same time.

Haunt (2019)

On Halloween night, a group of friends seeking thrills decides to visit an extreme haunted house located out of town, promoted by mysterious flyers. At first, it seems like the usual attraction with actors and tricks, but they soon realize the torture is not simulated. In Haunt, the house is a death trap run by a group of maniacs who have surgically modified their faces to look like the masks they wear (clown, witch, devil). The kids must navigate rooms full of real traps to survive.

Written by the creators of A Quiet Place and produced by Eli Roth, this film is a pure, unpretentious slasher that works wonderfully. It doesn’t reinvent the wheel but makes it spin perfectly. The tension is high, the masks are terrifying (especially when taken off), and the horror maze setting allows for a variety of creative murder scenarios. A solid, mean film, ideal for All Hallows’ Eve.

La Llorona (2019)

In Guatemala, elderly General Enrique Monteverde is tried for the genocide of the Maya people decades earlier but is acquitted on a technicality, sparking protests from the population besieging his mansion. While locked inside with his family, the general begins to hear a woman weeping at night. The new maid, Alma, a young indigenous woman with long black hair, seems to have a mysterious connection to that weeping. In La Llorona, the myth of the ghost crying for her dead children becomes the embodiment of historical justice coming to collect from those who believe themselves untouchable.

Jayro Bustamante transforms a folkloric legend into a refined and painful political horror. It is not a film of cheap scares (like the American version of the same name), but a supernatural drama about impunity and memory. La Llorona is not a monster; she is the voice of thousands of indigenous victims who received no justice. An elegant, slow, and atmospheric film demonstrating the maturity of Latin American horror cinema.

The Dark and the Wicked (2020)

Louise and Michael return to the remote family farm in Texas to say goodbye to their father, who is on his deathbed, bedridden and unconscious. They find their mother in a state of deep anguish, warning them not to come because “there is something here.” Shortly after, the mother commits suicide in a horrific way. Left alone with their dying father, in The Dark and the Wicked, the two siblings realize that a demonic presence is using the family’s grief and loneliness to feed itself, manipulating reality and driving them toward madness and death.

Bryan Bertino (The Strangers) directs the most nihilistic and frightening horror of recent years. It is a film about grief that offers no consolation: evil is an inevitable force that strikes randomly and destroys everything, regardless of how much people love each other. The atmosphere is suffocating, the farm sounds are used as psychological weapons, and the possession scenes are of rare cruelty. A masterpiece of tension that leaves you with a sense of absolute emptiness.

Host (2020)

During the COVID-19 lockdown, six friends decide to fight boredom by organizing a séance on Zoom, guided by a remote medium. One of the girls doesn’t take it seriously and invents a fake story about a ghost, breaking the circle of protection and insulting the spirits. In Host, what starts as a joking video call turns into a real-time nightmare when a demonic entity invades the girls’ homes, killing them one by one in front of their helpless friends’ webcams.

Rob Savage shot this film in 12 weeks during the actual quarantine, creating the definitive pandemic movie. Lasting only 56 minutes (the duration of a free Zoom call), it is a concentrate of pure fear. The smart use of video filters, connection lags, and virtual backgrounds makes the horror extremely realistic and modern. It proved that you can make a great horror movie with zero budget, just a brilliant idea and an internet connection.

Watcher (2022)

Julia, a former American actress, moves to Bucharest with her husband for his job. While he is always out, she spends her days alone in a large apartment with big windows. She notices a man constantly watching her from the window of the building opposite. Simultaneously, the city is terrorized by a serial killer who beheads women, called “The Spider.” In Watcher, the feeling of being watched becomes a certainty when Julia starts encountering the man at the supermarket and the cinema too, but no one, not even her husband, believes her, mistaking her fear for isolation-induced paranoia.

Chloe Okuno directs a Hitchcockian psychological thriller that is a perfect metaphor for gaslighting and daily female fear. Maika Monroe (It Follows) is extraordinary in conveying the anguish of not being believed. The film builds slow and nerve-wracking tension, playing on ambiguity until an explosive and bloody finale that vindicates the protagonist’s right to trust her own instincts.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision