Fear is humanity’s oldest and most powerful emotion, and horror cinema is its temple. But reducing this genre to simple “jump scares” is a mistake. Horror is a tool for social and psychological exploration: the monsters on screen are nothing more than projections of our collective anxieties, from historical traumas to personal phobias.

From Expressionist classics to the slashers of the 80s, up to the renaissance of contemporary “New Horror,” this guide is not just a list of scares. It is a journey into darkness divided by atmosphere, because every viewer has a different nightmare waiting for them.

The horror genre is an immense and intricate forest. Under the same label coexist the visceral blood of splatter and the invisible anxieties of ghost stories, the brutality of monsters, and the elegance of the gothic. There is no single way to be afraid.

To navigate it, you must ask yourself: what do I want to feel? Are you looking for physical repulsion, mental anguish, or a supernatural thrill? Do you want to see classic monsters or modern demons? Below we have analyzed the vital currents of the genre to guide you toward the specific type of thrill you are seeking.

🆕 Best Recent Horror

Longlegs (2024)

Lee Harker, a young FBI agent with clairvoyant abilities, is assigned to the cold case of a serial killer who has operated for decades without ever being seen at a crime scene. The killer, known as “Longlegs,” manipulates fathers into slaughtering their own families, leaving behind only cryptic letters. The investigation drags the agent into an abyss of occultism and Satanism, eventually revealing a terrifying personal connection to the murderer.

Directed by Osgood Perkins, this film became a viral phenomenon for its oppressive atmosphere. It is not a simple procedural, but a waking nightmare reminiscent of The Silence of the Lambs filtered through a demonic and hypnotic aesthetic. Nicolas Cage delivers one of the most grotesque and frightening performances of his career, in a film that works on pure dread rather than cheap scares.

When Evil Lurks (2023)

In a remote rural village in Argentina, two brothers discover that a neighbor is a “Rotten” (a man possessed by a demon about to be “born”). In an attempt to dispose of the body by following imprecise rules, they make the fatal mistake of moving it, triggering an epidemic of possession that spreads like an unstoppably virus. There are no priests, crucifixes, or exorcisms here: evil is a force of nature that corrupts everything it touches, including animals and children.

This Argentine film is the most brutal and uncompromising horror of recent years. Director Demián Rugna rewrites the rules of the possession movie by eliminating all religious hope. It is a nihilistic, violent, and shocking work that hits the viewer in the gut, breaking taboos that Hollywood would never dare touch. A masterpiece of tension and gore for those with a strong stomach.

Late Night with the Devil (2023)

Halloween, 1977. Jack Delroy is a late-night talk show host suffering from low ratings. For the Halloween special, he decides to bet big: he invites a parapsychologist and the young survivor of a Satanic cult to attempt a demonic possession live on national television. What starts as a cynical entertainment spectacle slowly transforms into a supernatural massacre that breaks the barrier between the audience and hell.

An indie gem that masterfully plays with the “Found Footage” format. The film is presented as the recovered recording of that cursed broadcast, with a perfect, grainy 70s aesthetic. It is a smart horror that satirizes the hunger for fame and the exploitation of pain, maintaining rising tension until a psychedelic and disturbing finale. David Dastmalchian is extraordinary in the role of the desperate host.

In a Violent Nature (2024)

A group of teenagers desecrates a locket in an abandoned fire tower in the woods, awakening Johnny, a vengeful and unstoppable spirit. The premise seems like a classic Friday the 13th, but the film completely flips the perspective: the camera doesn’t follow the victims running away; it follows the monster. We watch the film almost entirely from behind the killer’s shoulder as he walks placidly through beautiful nature, interrupted only by moments where he brutally slaughters those he meets.

It is an experiment in “Ambient Slasher” or “Slow Cinema Horror.” Director Chris Nash creates a hypnotic, almost contemplative work, where the beauty of the Canadian landscape contrasts with extreme graphic violence (the practical effects are disgusting and creative). It is an art film disguised as a horror movie, dedicated to those who love cinema that deconstructs genres. Unique in its kind.

A vision curated by a filmmaker, not an algorithm

In this video I explain our vision

Oddity (2024)

After the brutal murder of her sister Dani in the country house she was renovating, blind psychic and occult collector Darcy decides to investigate on her own. She arrives at the door of her brother-in-law (the victim’s husband) and his new girlfriend with an unsettling gift: a life-sized wooden mannequin from her curiosity shop, which seems to have a life of its own and the ability to reveal the truth about that night.

A taut and atmospheric Irish horror that proves you can create fear with minimal means and great direction. The film builds tension through empty spaces, silences, and the menacing presence of the inanimate object. It is a supernatural revenge story that blends the “Home Invasion” genre with a ghost story, delivering some of the scariest moments of the year without overusing digital effects.

1st Bite

Horror, romantic, by Hunt Hoe, Canada, 2006.

Gus is a charming man who works as a cook in an oriental restaurant in Montreal. His boss sends him to a remote island in Thailand to meet a master of Zen cuisine and improve the quality of his dishes. There he meets a mysterious woman named Lake who lives in a cave and informs him that the Zen cooking master is dead. Gus goes to live in the cave and begins a love affair with Lake. But the cook's psychological balance rapidly worsens, including hallucinations, alcohol and malaise. Lake doesn't want Gus to leave, but Gus feels that he needs to escape the island and that his life is in danger.

First Bite is a very original Canadian independent film that crosses different film genres in its narration, suddenly passing from romanticism to suspense to horror. Direction and editing that is never banal, supported by shots with wide-angle lenses that increase the tension and by a cast of actors in excellent shape that offer very intense and realistic interpretations. Between mysticism, black magic, love stories and tropical islands, Primo bite is the odyssey of a man who remains prisoner in a trap from which he can no longer escape, lost between passions and exotic foods. An escape from evil energies in search of spiritual meanings set between wild nature and metropolis.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish. French, German, Portuguese

The Substance (2024)

In a near-future dystopian world obsessed with image and youth, a revolutionary new biochemical product is launched on the black market: “The Substance.” By injecting it, the user can generate a younger, more beautiful, and “better” version of themselves, which literally exits their body like a shedding of skin. However, there is one iron rule for maintaining balance: the two bodies must share life, consciously alternating every seven exact days, without exception.

We include in this list a very recent title that, according to critics and audiences, has already established itself as an instant cult destined to define the decade. The Substance takes “body horror” to new levels of satirical and visual excess, fiercely criticizing the beauty industry, Hollywood ageism, and the social pressure on women to remain eternally young and perfect. The film is a neon, stylized, noisy, and grotesque nightmare, recalling the audacity of the best Cronenberg, Verhoeven, and Kubrick.

Strange Darling (2024)

In a remote area of the United States, characterized by isolated roads and suspended silences, a ruthless confrontation takes shape between two people who seem to have crossed paths by chance. Strange Darling opens with a frantic escape, a tight chase that immediately becomes an enigma: who is really running and who is hunting? The story is unveiled through a series of temporal segments that interlock like distorted fragments, progressively revealing intentions, deceptions, and hidden impulses. The truth constantly shifts, collapsing all certainties and reversing the meaning of what was seen just minutes before.

The film builds an almost unsustainable tension, where fear does not arise from the supernatural but from human behavior, which is unpredictable and visceral. The two protagonists face each other as if trapped in a dark and unresolved bond, a relationship made of manipulation, ambiguous emotional calls, and a past that surfaces in sudden waves. Every detail—a gesture, a silence, a change of direction—becomes a threat, a clue, a further psychological twist.

Indie Horror and Cult Movies

Far from the commercial logic of Hollywood, independent horror is where the genre renews itself and truly bites. Without the censorship of major studios, these films can afford to be radical, grotesque, and politically incorrect. Here you will find the “Cult” works and the new voices rewriting the rules of fear.

👉 BROWSE THE CATALOG: Stream Indie Horror Now

Psychological Horror and Mind Games

Here the monster has no fangs but lives inside the protagonist’s head. Psychological horror does not seek the cheap scare, but deep discomfort. Often set in enclosed spaces or asylums, these films explore madness, paranoia, and the collapse of reality. It is the perfect subgenre for those who want an experience that leaves a lingering sense of unease for days.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Psychological Horror Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Asylum Horror

The Supernatural: Ghosts, Witches, and Exorcisms

It is the realm of the invisible and the unexplained. Whether it’s haunted houses, demonic possessions, or ancient curses, this subgenre touches our ancestral fear of death and the afterlife. From classic ghost stories to films about witches and esotericism, here tension arises from the anticipation of seeing what should not exist.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Ghost Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Witches Movies

👉 GO TO THE SELECTION: Films on Esotericism

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Exorcism Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Supernatural and Paranormal Movies

The Monsters: Zombies, Vampires, and Creatures

Fear takes physical form. This is the cinema of the “creature,” where humanity is threatened by lethal predators. From Zombies (a metaphor for contagion and the masses) to the decadent elegance of Vampires, up to the brutality of Werewolves and Aliens. It is the genre that combines action with fear, often with special effects that made cinema history.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Zombie Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Vampire Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Werewolf Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Alien Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Monster Movies

Splatter, Body Horror, and Cannibals

For strong stomachs only. Here fear becomes physical, visceral, tactile. “Body Horror” explores the mutation and destruction of the human body, while Splatter and the Cannibal subgenre push graphic violence to the extreme. It is not cinema for everyone, but for those seeking a shocking experience that breaks every taboo regarding flesh and death.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Splatter Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Body Horror

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Cannibal Movies

Folk Horror, Gothic, and Atmospheres

Fear here comes from the landscape, the past, and traditions. The Gothic (especially Italian) works on atmospheres, castles, and shadows. Folk Horror takes us into isolated countrysides, among pagan rituals and closed communities. It is an elegant, slow horror that envelops you like fog.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Gothic Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Italian Gothic Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Folk Horror

Horror from the World

Fear speaks different languages. Asian horror (J-Horror and Korean) is famous for its vengeful spirits and icy atmospheres. Spanish horror often mixes historical drama with the supernatural. Exploring these cinematographies means discovering new ways to be scared, far from American clichés.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Japanese Horror

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Korean Horror

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Spanish Horror

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Italian Horror

Horror for Special Occasions (Halloween and Comedy)

Sometimes fear is a party. Halloween night requires specific films, made of pumpkins, masks, and autumnal atmospheres. And let’s not forget that fear is the cousin of laughter: Horror Comedy mixes blood and gags for entertainment that is lighter but always biting.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Halloween Movies

👉 GO TO THE LIST: Funny Horror Movies

The Golden Decades: 80s and 90s

If you are looking for a nostalgic flavor or want to catch up on the classics, the temporal division is fundamental. The 80s were the golden age of practical effects and slashers; the 90s introduced irony and meta-cinema.

👉 GO TO THE LIST: 80s Horror

👉 GO TO THE LIST: 90s Horror

Horror Movies at the Origins of Cinema

Horror cinema almost begins with the invention of the cinema itself. The first horror film is attributed to Georges Melies and was entitled Le manoir du diable, followed by another short film by the French director-magician The cursed cave.

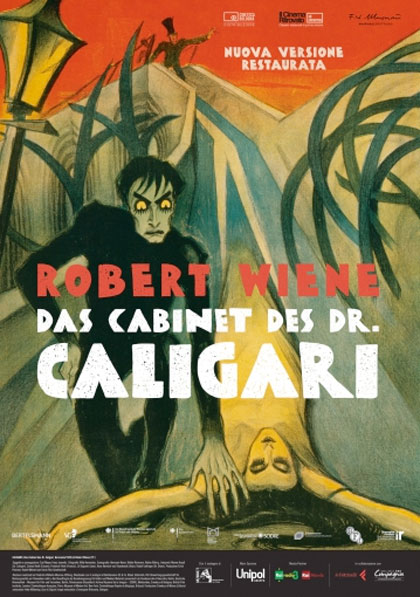

The best horror films of the silent era have marked the history of films as Murnau’s Nosferatu the vampire, Dreyer’s Vampyr, or Doctor Caligari’s Cabinet, the film that started the motion picture movement expressionism. In those years, Horror cinema would have had a great flowering among German directors.

In addition to avant-garde cinema, Hollywood also produces horror masterpieces that would have remained etched in memory, such as James Whale’s Frankenstein and Tod Browning’s Dracula. In the 1920s there was the appearance of the first deformed monster in the history of cinema, The Hunchback of Notre Dame. In 1925 Hollywood produced another unforgettable film The Phantom of the Opera, starring actor Lon Chaney.

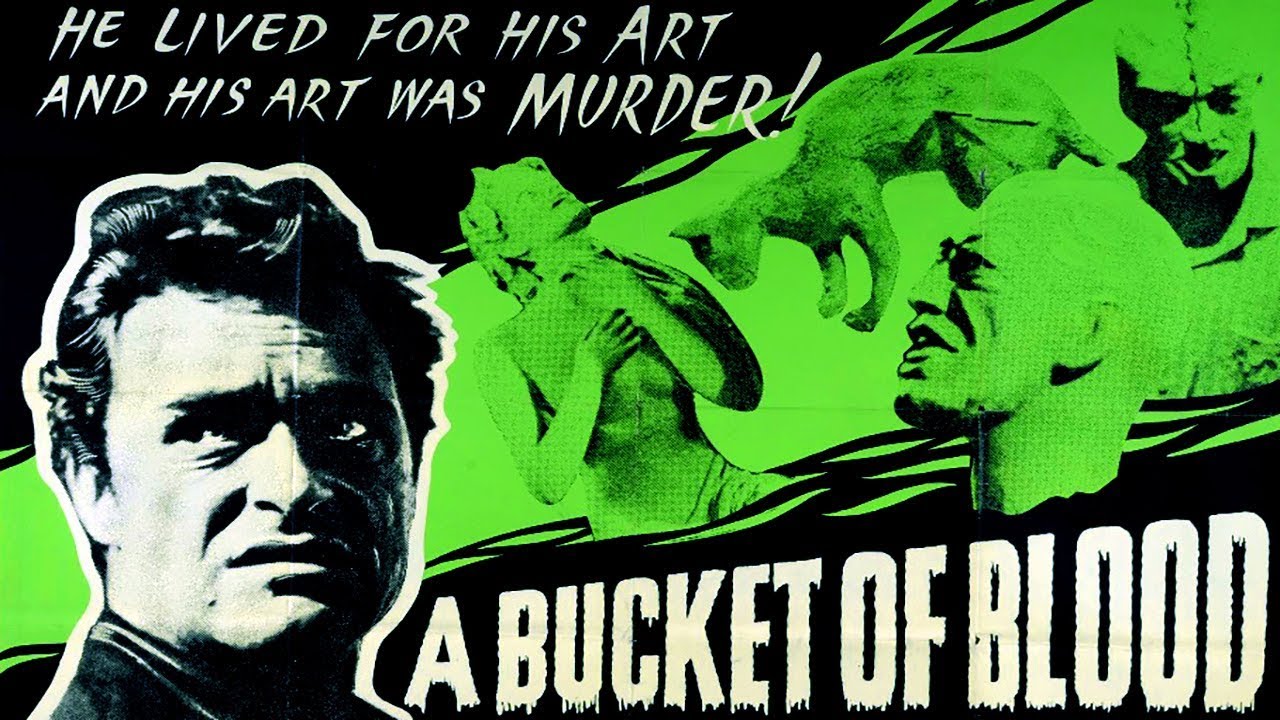

A Bucket of Blood

Comedy, Crime, by Roger Corman, United States, 1959.

Produced on a budget of $ 50,000, it was shot in five days by low-budget B movie king Roger Corman. One night, after hearing the words of Maxwell H. Brock, a poet who performs at The Yellow Door cafe, the obtuse waiter Walter Paisley returns home to try to create a sculpture of the face of the hostess Carla, but accidentally kills the cat. Instead of giving the animal a proper burial, Walter covers the cat with clay, leaving the knife stuck inside. The next morning Walter shows the cat to Carla and her boss Leonard. Carla is enthusiastic about the work and convinces Leonard to exhibit it in his bar. Walter receives praise from Will and the other beatniks in the cafe.

Food for thought

Art kills and hands real life over to immortality. What are the characters of a film, a painting or a sculpture if not non-human crystallizations, theorems and representations of people we have seen, heard, dreamed, met in real life?

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920)

The Golem: How He Came into the World is a 1920 silent film directed by Carl Boese and Paul Wegener, who also stars. The film is based on the novel of the same name by Gustav Meyrink, published in 1915.

The film tells the story of a 16th-century rabbi in Prague who creates a golem, a being of clay animated by magic, to protect his people from pogroms. The golem is initially a faithful servant but soon becomes dangerous and uncontrollable. The rabbi is forced to destroy the golem to save the city.

The Golem: How He Came into the World is a film that explores the theme of the conflict between good and evil. The golem represents the dark side of human nature. It is a powerful and destructive being that can be used for both good and evil. The film also explores the theme of creation and its consequences. The golem is a work of creation, both by Rabbi Löw and by God. The film was shot in an Expressionist style, which emphasizes angular forms and lines. The film is characterized by a dark and unsettling atmosphere, which helps to create a sense of suspense and fear. The film is considered a classic of German expressionist cinema. It is one of the most important films of the genre, and has influenced many other horror and fantasy films.

The Phantom Carriage (1921)

The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen; literally “The Cart Driver”) is a 1921 silent film directed by Victor Sjöström, based on the novel of the same name by Selma Lagerlöf published in 1912.

The story begins with David Holm, a young worker living in Stockholm. David is a violent and reckless man who neglects his wife Edit and their young son. One night, while drunk, David kills a man. The next day, David wakes up in the cemetery, where he meets a mysterious cart driver. The cart driver tells him that David is destined to drive his phantom carriage, which collects the souls of the dead who have lived a life of sin. David tries to flee from the cart driver, but it is in vain. The cart driver leads him into a world of shadows and terror, where David must face the consequences of his actions.

The Phantom Carriage is a film that explores the theme of sin and redemption. David is a man who has committed a grave sin but still has the possibility of being redeemed. The film is set in a dark and unsettling world, which represents David’s interior world. The cart driver represents David’s conscience, which forces him to confront his actions. The film has an open ending, which leaves the audience with a sense of hope. David has the possibility of being redeemed, but he must face a long and difficult path.

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922)

Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler) is a 1922 silent film directed by Fritz Lang, based on the novel of the same name by Norbert Jacques.

The film tells the story of Mabuse, a criminal mastermind who controls the city of Berlin through a network of criminals and corruption. Mabuse is a complex and multifaceted character who represents the dark side of human nature. The film begins with Mabuse’s escape from an asylum. Mabuse is a criminal mastermind who controlled the city of Berlin through a network of criminals and corruption. Mabuse was interned in an asylum, but managed to escape.

Dr. Mabuse the Gambler is a film that explores the theme of evil and good. Mabuse represents evil, while Commissioner von Wenk represents good. The film is set in a gloomy and unsettling Berlin, which represents Mabuse’s interior world. Mabuse is a criminal genius, and his plans are always well-conceived.

Nosferatu the Vampire (1922)

Thomas Hutter, a real estate agent from the fictional city of Wisborg, is sent to Transylvania to finalize the sale of a house with the mysterious Count Orlok. Hutter soon discovers that the Count is an ancient vampire who travels carrying crates full of unhallowed earth and an unstoppable pestilence, with the goal of reaching Hutter’s wife, Ellen, the only pure force capable of stopping him.

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s work is not only the founding father of vampire cinema but one of the unsurpassed peaks of German Expressionism, a movement that sought to visualize the inner distortion of reality. What makes Nosferatu terrifying even today, more than a century after its release, is its ability to visualize disease and decay in a tangible way. Unlike the aristocratic and seductive Dracula who would be codified by Hollywood with Bela Lugosi, the Orlok played by Max Schreck is a biological abomination, a skeletal creature resembling an anthropomorphic rat that embodies the atavistic fear of contagion and plague, a resonant theme in a Europe that had just emerged from the Spanish Flu.

A Page Of Madness

Drama, horror, by Teinosuke Kinugasa, Japan, 1926.

A page of madness is an independent film shot on a nearly non-existent budget and then lost for forty-five years. Fortunately the director rediscovered it in his archive in 1971. It is a film made by a group of Japanese avant-garde artists, the School of new perceptions. A movement that had as its objective to overcome the naturalistic representation. In a country asylum, in torrential rain, the caretaker meets patients with mental illness. The next day a young woman arrives who is surprised to find her father there who works as a caretaker. The woman's mother first went mad because of her husband when she was a sailor. The husband has decided to change jobs to stay close to his wife in the asylum and take care of her. Her daughter tells her father that she will marry soon, but the father is worried because he fears, according to popular rumors of the time, that the mother's mental illness will be inherited by her daughter. If the young husband and his family found out about his mother's madness, the marriage would fall apart. The caretaker tries to take care of his wife during her work as she gets beaten up by other inmates, but this interferes with her role and is scolded by the head of the asylum. Slowly the keeper loses contact with reality and its boundaries from the dream. He begins to daydream about winning the lottery when his daughter meets him again to tell him that his marriage is in trouble. The man thinks of taking his wife out of the asylum to hide her existence and solve every problem. Teinosuke Kinugasa is the director of some of the best Japanese films of the 1920s. A page of madness has been compared to the great German expressionist films. It is an experimental film, of extreme avant-garde, which seems to anticipate the atmospheres and themes that would have made David Lynch famous many years later. Nightmares, distortions, blurs, double exposures and photographic deformations: a film that explores the furthest boundaries of moving images. Then there are those masks set in an eternal succession of bars, locks and corridors that fuel the sense of fear and loss of the various protagonists to excess.Yasunari Kawabata, the writer of the story, won the Nobel Prize for literature in the 1968.

Without dialogue

The Hands of Orlac (1924)

The Hands of Orlac” is a 1924 film directed by the Austrian director Robert Wiene. It is a silent film from the era of expressionist cinema German, known for its unsettling storyline and its use of distorted visual techniques.

The film follows the story of Paul Orlac, a celebrated pianist who loses both of his hands in a train accident. Pressured by his ambitious wife, Yvonne, Orlac undergoes a hand transplant that allows him to play the piano again. However, Orlac begins to fear that the new hands are those of an assassin, as he begins to experience disturbing visions and nightmares.

The film explores themes such as identity, psychology and inner conflict, using a highly stylized visual approach. Wiene’s direction uses lighting and camera angles to create a sense of tension and disorientation, while the interior and costume design is highly stylized and surreal. The film has been the subject of numerous reshoots and adaptations, including a 1935 adaptation starring Peter Lorre and a 1960 remake titled “The Hands of Orlac.” The film is considered a classic of German Expressionist cinema and influenced a number of later directors, including Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch.

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

TThe Phantom of the Opera (1925) is a silent film directed by Rupert Julian. It is based on the novel of the same name by Gaston Leroux, which tells the story of Erik, a brilliant but disfigured musician who lives hidden in the basements of the Paris Opéra; he is willing to do anything to bring the young singer Christine, with whom he is secretly in love, to success.

The Phantom of the Opera is a complex and multifaceted film that can be interpreted in many ways. One interpretation is that the film is a warning about the dangers of obsession. The Phantom is a talented musician, but his obsession with Christine leads him to madness. He is willing to do anything to possess her, even if it means harming her or others.

Another interpretation is that the film is a metaphor for the creative process. The Phantom is a tormented artist who finds solace in his music. He is able to express himself through his music in a way he cannot in the real world. Christine is a muse for the Phantom, and her voice inspires him to create. The Phantom of the Opera is a classic film that has been adapted into many other forms, including stage musicals, television series, and video games. It is a story of love, obsession, and the dark side of the human psyche.

The Best Horror Movies of the 30s and 40s

In the 1930s, Universal specialized in horror movies, creating a long gallery of monsters. After Dracula and Frankenstein they produced films such as The Mummy, The Invisible Man. Other studios like Paramount and Warner Brothers produced fewer horror movies, but with some good results like The Wax Mask and Dr. Jekyll.

In the 1940s Universal focuses on werewolves with films such as The Wolf Man, and on a long series of films about Frankenstein. RKO produces The Leopard Man, I walked with a zombie, the kiss of the panther, directed by Jacques Tourneur.

Frankenstein (1931)

Frankenstein (1931) is a classic horror film directed by James Whale and starring Colin Clive as Henry Frankenstein and Boris Karloff as the creature. The film is based on the 1818 novel of the same name by Mary Shelley.

Dr. Henry Frankenstein is a brilliant scientist obsessed with the creation of life. He manages to assemble a creature from body parts, but the creature is deformed and monstrous. Frankenstein is horrified by his creation and abandons it. The creature is left to fend for itself and quickly learns that it is not accepted by society. It is feared and despised by everyone it meets. The creature becomes angry and vengeful and begins to kill the people who have wronged it.

Frankenstein is one of the most influential horror films ever made. It has been remade and adapted countless times, and it has inspired countless other films, books, and television series. The film’s iconic images and characters have become part of popular culture.

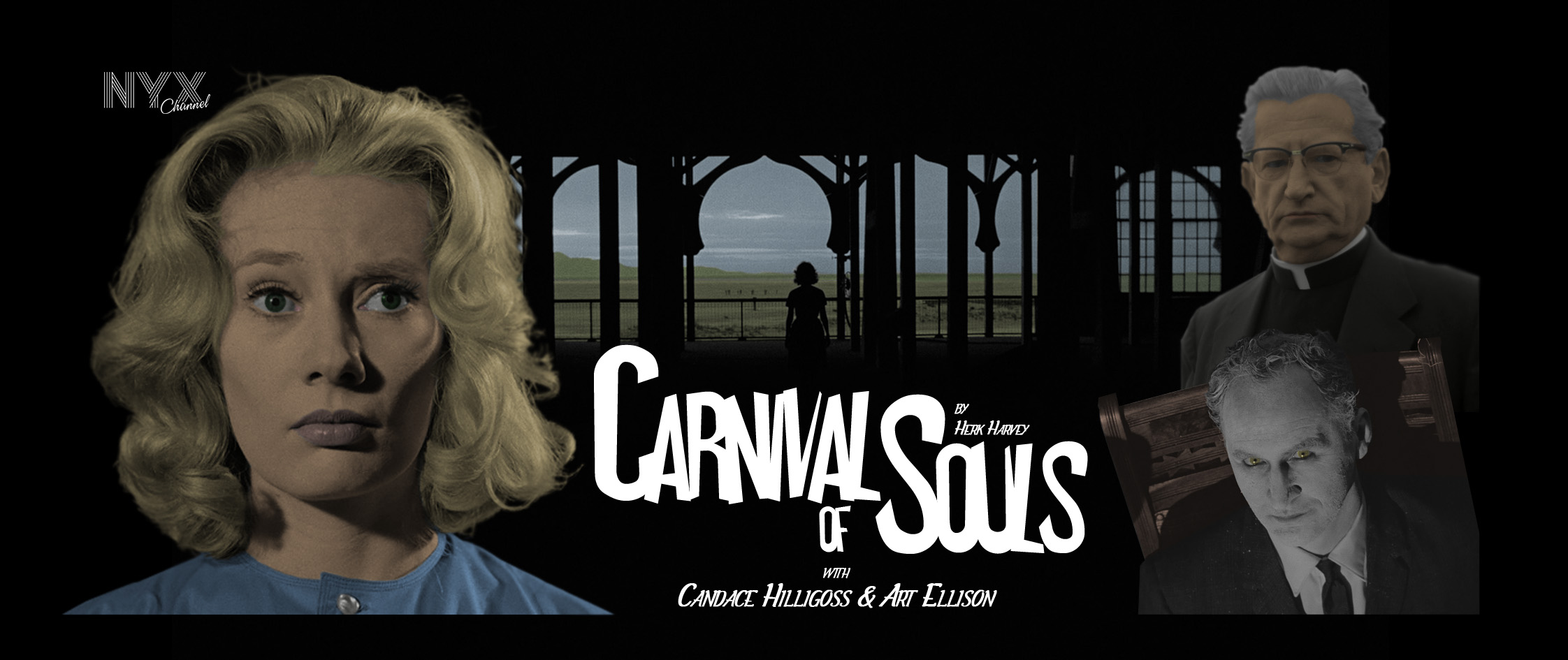

Carnival of souls

Horror, by Herk Harvey, United States, 1962.

Mary Henry emerges unscathed from a car accident that killed her two companions, and sets off on a strange adventure in Salt Lake City, where she finds herself drawn to a dilapidated lakeside pavilion and haunted by a ghostly figure (played by same director). A low-budget ($ 30,000) horror masterpiece that went unnoticed at the time of its release, it has become a cult film in the United States since the late 1980s. Sounds and images that have inspired directors such as George Romero and David Lynch (the masked man from "Lost Roads").

LANGUAGE: english

SUBTITLES: italian

Dracula (1931)

Dracula (1931) is a classic American horror film directed by Tod Browning and starring Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula. The film is based on the 1897 novel of the same name by Bram Stoker.

The film begins with a young English solicitor, Renfield (Dwight Frye), traveling to Transylvania to sell a castle to Count Dracula (Bela Lugosi). Renfield is warned by locals about Dracula, who is known to be a vampire, but he ignores their warnings. When Renfield arrives at Dracula’s castle, he is greeted by the Count himself. Dracula is a charming and sophisticated man, but he also has a dark side. He hypnotizes Renfield and turns him into his slave.

Dracula is one of the most influential horror films ever made. It has been remade and adapted countless times, and it has inspired countless other films, books, and television series. The film’s iconic images and characters have become part of popular culture. Dracula is considered a classic of horror cinema. It is a well-made and thought-provoking film that explores important themes such as the nature of good and evil, the dangers of lust and temptation, and the importance of faith. The film has had a lasting impact on popular culture and continues to be appreciated by audiences today.

Fun fact: Bela Lugosi wore fake teeth in the film, but they were so uncomfortable that he could barely speak with them.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931)

It is a 1931 American horror film, directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starring Fredric March, who plays a skilled doctor who discovers a new formula that can unleash the satanic forces in people.

The film is an adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, about a man who takes a cure that transforms him from a mild-mannered man of science into a bloodthirsty madman. The film was a success upon its release. Nominated for 3 Academy Awards, March won the award for Best Actor.

Dr. Henry Jekyll (Fredric March), a quiet English doctor in Victorian London, argues that both bad and good impulses are hidden in every man. He is crazy about his future wife Muriel Carew (Rose Hobart) and wants to marry her.

Her father, Brigadier General Sir Danvers Carew (Halliwell Hobbes), orders them to wait. One evening, while walking home with his colleague, Dr. John Lanyon (Holmes Herbert), Jekyll meets a bar singer, Ivy Pierson (Miriam Hopkins), who is struck by a man outside her house. Jekyll drives the man away and takes Ivy to his house to take care of her.

The Mummy (1932)

It is a 1932 American horror film directed by Karl Freund. John L. Balderston’s film screenplay was adapted from a screenplay written by Nina Wilcox Putnam and Richard Schayer. Launched by Universal Studios as part of the Universal Classic Monsters franchise, the film stars Boris Karloff, Zita Johann, David Manners, Edward Van Sloan and Arthur Byron.

In the film, Karloff plays Imhotep, an ancient Egyptian mummy who was disposed of for trying to revive his deceased lover, Ankh-esen-amun. After being discovered by a group of excavators, he disguises himself as a modern Egyptian called Ardeth Bey and searches for Ankh-esen-amun, who he thinks has reincarnated into the contemporary world. While far less culturally impactful than its forerunners Dracula and Frankenstein, the film was still a good hit, spawning numerous sequels, remakes, and spin-offs.

Freaks (1932)

Freaks (1932) is a horror film directed by Tod Browning and produced by MGM. The film stars Wallace Ford, Leila Hyams, and a large cast of performers with disabilities.

The film tells the story of Hans (Ford), a little person who falls in love with Cleopatra (Hyams), a trapeze artist. Cleopatra is only interested in Hans’s money and plots to kill him with the help of her lover, Hercules (Harry Earles). The other circus performers, all “freaks,” learn of Cleopatra’s plan and decide to take revenge. They lure Hans and Cleopatra into the circus funhouse, where they attack them.

Freaks was a critical and commercial failure upon release. The film was banned in many countries due to its disturbing content. However, the film was later re-evaluated and is now considered a classic of horror cinema. Freaks had a profound impact on the horror genre. The film is one of the first horror films to feature performers with disabilities. The film has also been praised for its dark and subversive themes.

Dementia

Horror, noir, by John Parker, United States, 1955.

It's night. A woman suddenly wakes up from a nightmare in a seedy hotel in the Los Angeles suburbs. She leaves the room and wanders the neighborhood. She meets a dwarf who sells newspapers with the title "Mysterious Stabbing". In a dark alley, a drunkard harasses her and a policeman rescues her. She then she meets a smartly dressed man with a thin mustache. The man gives her a flower and convinces her to get into the limo with a rich fat guy. As they drive through the city, the man thinks back to his childhood trauma and the violent father who stabbed him with a knife after he shot his unfaithful mother. The rich man takes her to have fun in several nightclubs and then to her apartment. He first ignores the woman while she gorges herself with a big meal. She seduces him, and he approaches her excitedly.

A visionary and hallucinatory nightmare, without dialogue, during a night of a lonely woman in Los Angeles. Between horror, film noir and expressionist film, initially conceived as a short film by Parker based on a dream told him by his secretary, Barrett, who also became the film's interpreter. The film was blocked by the New York State Film Board before being released in theaters in 1955. Later Jack H. Harris bought it and created a new version, with a different cut of editing, also adding a voiceover. and changing the title. This is the original version.

Without dialogue

The Invisible Man (1933)

It is a 1933 American science fiction horror film directed by James Whale based on H. G. Wells’s 1897 novel The Invisible Man, produced by Universal Pictures, and starring Gloria Stuart, Claude Rains, and William Harrigan.

The film stars Dr. Jack Griffin (Rains), covered in bandages with his eyes obscured by dark glasses, the result of a secret experiment that makes him invisible, who takes lodging in the town of Iping until his landlady discovers the secret. Lion returns to Dr. Cranley’s (Henry Travers) research laboratory and reveals his invisibility to Dr. Kemp (William Harrigan) and Cranley’s wife Flora (Gloria Stuart), who discover that Griffin has become dangerous, even committing murders.

The film had been in promotion for Universal as early as 1931, when Richard L. Schayer and Robert Florey recommended that Wells’s novel would be an excellent follow-up to the horror film Dracula. Universal chose to make Frankenstein in 1931 instead. This led to a series of adjustments to the film’s screenplay, as well as a variety of potential directors. Upon the film’s launch in 1933, it was a great commercial success for Universal and received solid reviews from numerous magazines. The film spawned numerous follow-ups that were not associated with the initial film in the 1940s. It is one of the favorite films of directors John Carpenter, Joe Dante, and Ray Harryhausen.

Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933)

It’s a mystery horror movie 1933 American directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Lionel Atwill, Fay Wray, Glenda Farrell and Frank McHugh. It was released by Warner Bros. and recorded in two-color Technicolor.

Ivan Igor (Lionel Atwill) is a sculptor who runs a wax museum in London. He is a cruel and sadistic man who enjoys torturing his victims. Igor’s partner, Joe Worth (Edwin Maxwell), wants to burn down the museum and collect the insurance money. Igor refuses, so Worth sets fire to the museum himself. Igor is trapped inside the burning museum, and his face is severely disfigured. Years later, Igor has rebuilt his life in New York City. He has opened a new wax museum and is now married to a beautiful woman named Florence (Dorothy Burgess). However, Igor’s old vices never die. He begins to ensnare people and create wax statues of them.

Mystery of the Wax Museum was a critical and commercial success. It was one of the first horror films to be released in color. The film has influenced countless other horror films, including House of Wax (1953) and Chamber of Horrors (1966). Mystery of the Wax Museum is considered a classic of horror cinema. It is a well-made and suspenseful film with memorable characters and iconic images. The film has had a lasting impact on popular culture and continues to be appreciated by audiences today.

Cat People (1942)

Cat People is a 1942 horror film directed by Jacques Tourneur. The film tells the story of Irena Dubrovna, a young woman who is cursed to transform into a panther every time she feels excited or threatened. Irena falls in love with Oliver Reed, a zoologist, but is afraid to reveal her secret to him. When Oliver’s ex-girlfriend, Alice Moore, arrives in town, Irena becomes jealous, and her dark side begins to emerge.

Irena Dubrovna is a young woman who is haunted by a dark secret: she is cursed to transform into a panther every time she feels excited or threatened. Irena’s curse is rooted in her family history; her mother was also a cat woman, and her grandmother was killed by a panther.

Irena becomes jealous of Alice and her relationship with Oliver. One night, Irena follows Alice home and becomes so angry that she transforms into a panther. Alice is attacked and killed by the panther, but Irena escapes. Cat People had a profound impact on the horror genre. The film helped to popularize the genre of psychological horror and is considered one of the most influential horror films of all time. Cat People has also been cited and parodied in numerous other films, television shows, and video games.

The Best Horror Movies in the 50s and 60s

In the 50s, thanks to technology and special effects, horror cinema crosses science fiction to tell the dark atmosphere of the cold war, with films such as The Thing from Another World by Howard Hawks and Invasion of Body Snatchers.

Between the end of the 50s and the beginning of the 60s the first production company specialized exclusively in horror movies was born, the Hammer film. With director Terence Fisher they produced prototypes of what would become modern horror movies. Some titles to remember are The Mask of Frankenstein, Dracula the Vampire, the remake of The Mummy.

Roger Corman produced countless horror movies, specializing in so-called b movies, and bringing several short stories by Edgar Allan Poe to the screen. In the 1960s, horror cinema becomes more explicit and more violent. Horror films are also used to describe fears related to politics and technological and consumer development, for example in the film Assault on the Earth.

At the end of the 60s the classic monsters take a back seat and Horror cinema becomes psychological with films like Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Michael Powell’s The Killing Eye. Numerous low-budget independent films are also made such as Blood Feast (1963) and Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964) that usher in the bloodiest splatter genre. In 1968 George Romero brings the Zombie genre to the fore. With a very low budget he made one of the most important horror movies of the time The night of the living dead.

Faust

Horror, by F. W. Murnau, German, 1926.

Faust is an elderly scholar who has lost faith in life. He is defeated by his inability to help others and by his awareness of his own mortality. One day, he meets Mephistopheles, who offers him a pact: in exchange for his soul, Mephistopheles will give him eternal youth and power. Faust accepts the pact and Mephistopheles takes him to a world of luxury and pleasure. Faust falls in love with Gretchen, a young innocent woman, but their love is thwarted by Mephistopheles.

Faust is considered one of the greatest silent films ever made. It is a visually stunning film, with Murnau's use of expressionist imagery and symbolism to create a dark and atmospheric world. The film also features some of the most iconic scenes in cinema history, such as the sequence in which Faust and Mephistopheles fly on a magic carpet. In addition to its artistic merits, Faust was one of the last major German films produced before the rise of the Nazis. The film's dark and expressionist style later influenced directors such as Orson Welles and Fritz Lang. It is a visually stunning and thought-provoking film that explores the themes of temptation, redemption, and the human condition.

LANGUAGE: German

SUBTITLES: English, Spanish, French, Portuguese

Them! (1954)

It is an American Horror science fiction film from 1954 by Warner Bros. Written by David Weisbart, directed by Gordon Douglas, and played by James Whitmore, Edmund Gwenn, Joan Weldon and James Arness.

The film is based on an adaptation of George World Yates’ story, which later became the screenplay for a Ted Sherdeman film and also adapted by Russell Hughes. This film is only one of the first films on the nuclear monsters of the 1950s, and also the first feature film on the “big insect” to use parasites as monsters.

A nest of huge irradiated ants is discovered in the New Mexico desert; They become a national threat when it turns out that two young queen ants have escaped to build new nests. National research eventually leads to a battle in the Los Angeles exhaust pipes system.

The Undead (1957)

A woman is put into a psychic trance and sent back in time directly into the body of one of her medieval ancestors, who is doomed to die as a witch. She escapes and a real witch named Livia (Allison Hayes), who works with the devil. There is also another witch, a rogue who helps Livia, and one of the psychics who travels back in time with her.

Produced and directed by Roger Corman, this is an offbeat and entertaining B-movie: violence, reincarnation, time travel, comedy and fun. There are funny scenes with the witch and the leprechaun turning into animals.

Even the undertaker is entertaining with his witty rhymes and discussions. Satan is awesome, with his constant laughter and a huge pitchfork. On Saturdays, he summons a trio of dead girls to climb from the grave and dance.

The film is particularly notable for actress Hayes’ appearance, her very skintight dress. Hayes was arguably a 1950s B-movie starlet, mostly due to her appearance in Attack of the 50-Foot Woman. The film was shot in six days on a budget plan of $70,000, in an old supermarket. It has a cult following among fans of scary movies, drive-ins, small budget independent films. If you like any of those, you need to check them out next.

I Vampiri (1957)

I Vampiri is a 1957 Italian horror film directed by Riccardo Freda and finished off by the film’s cinematographer, Mario Bava. In the cast Gianna Maria Canale, Carlo D’Angelo and Dario Michaelis.

The film deals with a series of murders of girls who are discovered with blood drainage tubes. The newspapers talk about a serial killer called the Vampire, which motivates the young journalist Pierre Lantin to investigate the crimes.

At the time of its release the film was perceived as an original and strange object for followers of the horror genre. The really scary scenes boil down to a few sequences.

The film established the requirement for an aesthetic design that would be the framework for many similar Italian horror films: cobwebs, creaking doors, degeneration and fantastic lighting. Anyone curious about Italian horror cinema should see it: an ignored and underrated film, with suggestions from neorealist cinema.

Black Sunday (1960)

In 17th-century Moldavia, Princess Asa Vajda, suspected of witchcraft, is condemned by the Inquisition and dies cursing her own family, held responsible for her fate. In the 19th century, the doctors Kruvajan and Gorobec, en route to a medical conference, come across Asa’s coffin and accidentally awaken her. She systematically sets out to seek revenge…

The film was panned by the Italian critics while immediately appreciated in France as a “pictorial” masterpiece. It is undoubtedly one of Mario Bava‘s best films with sequences of great charm and horror. The English version was marred by a mediocre dubbing.

English critics initially appreciated it for its low-budget production. In subsequent years, the film was reevaluated and considered among the best horror films ever made: a festival of the forbidden that unleashes an adolescent interest in the supernatural world, hailed as the masterpiece of Italian gothic horror.

The beautifully composed chiaroscuro cinematography, the expressionistic style, and the direction all lend the film a unique atmosphere. It is cinema in its most abundant and grandiose form, brimming with resonant imagery.

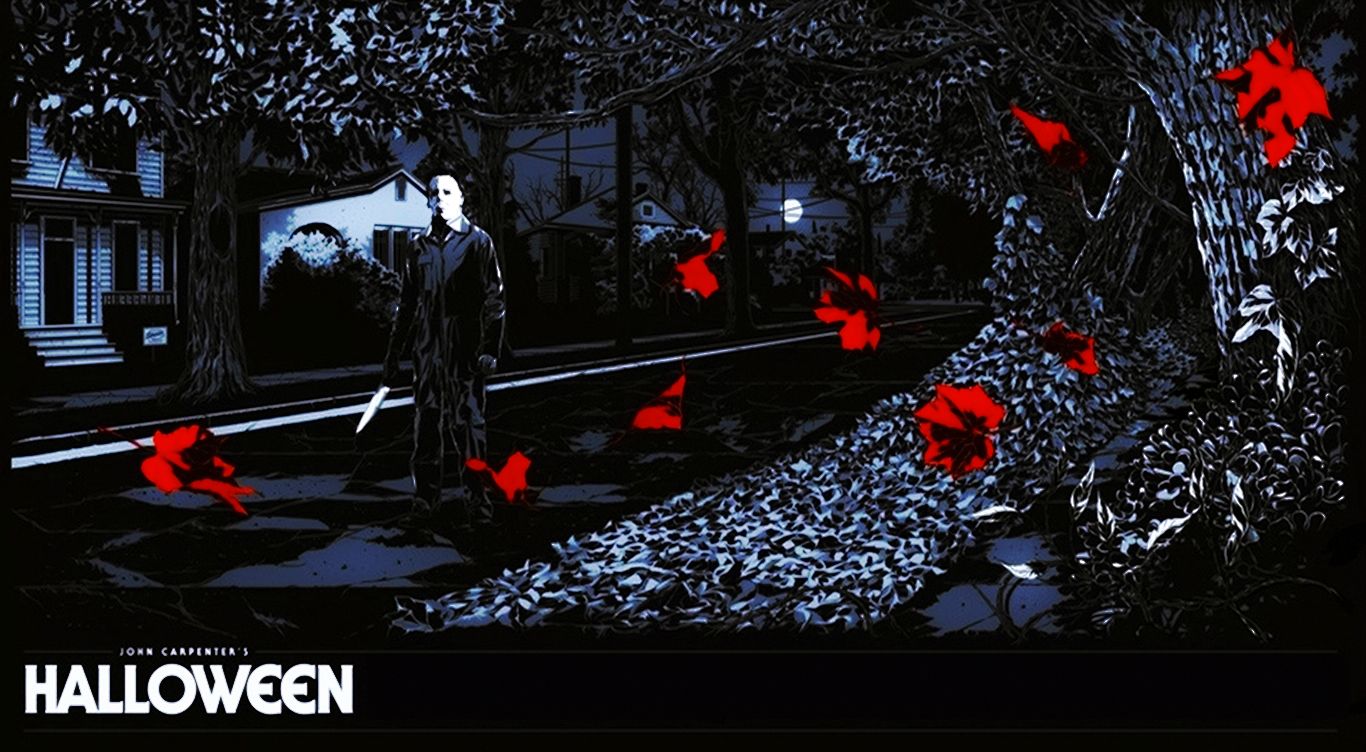

Halloween

Horror, by John Carpenter, United States, 1978.

An independent film shot on a very small budget, it grossed over $ 80 million worldwide at the time. It is the most successful slasher movie and one of the 5 most profitable films in the history of cinema, which has become a cult with countless sequels and reboots. Carpenter describes the remote American province in an extraordinary way and raises the tension for over an hour, without anything happening, with a linear and effective direction, and with hypnotic music created by himself. A brilliant director who manages, with a few simple elements and a small production, to create a horror destined to remain in the worldwide cinematic imagination.

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

Psycho (1960)

Psycho (1960) is an American psychological horror film directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Janet Leigh, Anthony Perkins, John Gavin, and Vera Miles. The film is based on the 1959 novel of the same name by Robert Bloch.

Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), a secretary from Phoenix, Arizona, steals $40,000 from her employer and drives to California to start a new life with her boyfriend, Sam Loomis (John Gavin). Along the way, she stops at a remote motel managed by Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), a young man who lives with his overbearing mother.

Psycho is considered one of the most influential horror films ever made. It was one of the first films to focus on the psychological motivations of a killer. The film’s shower scene is one of the most iconic scenes in cinema history. It is a well-made and suspenseful film with complex characters and iconic images. The film has had a lasting impact on popular culture and continues to be appreciated by audiences today.

Fun fact: The shower scene was filmed in just 45 seconds, but it took seven days to edit. This horror film is based on a true story of Ed Gein and the murders in Wisconsin.

Eyes Without a Face (1960)

The brilliant and obsessive surgeon Dr. Génessier, consumed by guilt for having horribly disfigured his daughter Christiane in a car accident he caused, kidnaps young women with the help of his assistant Louise. His goal is to remove their intact faces and attempt to surgically transplant them onto the girl. Christiane, forced to live reclusive in her father’s villa wearing an inexpressive white mask that adheres like a second skin, wanders like a specter through the rooms, a silent witness and reluctant accomplice to the atrocious crimes committed in the name of her “recovery.”

Georges Franju creates an work of lyrical and disturbing beauty with Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage), a poetic horror that mixes dark fairy tale with the most explicit surgical gore. The film is visually dominated by the jarring contrast between the formal elegance of the staging, the ethereal black and white photography, and the graphic and clinical brutality of the face removal operation. This sequence, which caused numerous audience members to faint at the time, still retains its disturbing force today due to its cold, methodical realism.

Peeping Tom (1960)

Peeping Tom is a 1960 British psychological horror film directed by Michael Powell. It stars Karlheinz Böhm, Moira Shearer, Anna Massey, and Esmond Knight.

The film tells the story of Mark Lewis, a camera operator who kills women and records their reactions with a hidden camera. Mark is a man tormented by childhood trauma, and his obsession with cinema is a way to control and dominate his victims. The film is known for its unsettling atmosphere and its innovative use of the camera. Powell uses the camera to create a sense of suspense and voyeurism and to explore the protagonist’s psychology.

Peeping Tom is a film that explores the dark side of the human mind. Mark Lewis is a man tormented by childhood trauma, and his obsession with cinema is a way to control and dominate his victims. The film can be interpreted as an allegory of the violence of modern society. Mark is a product of his culture, and his violence is a reflection of the violence that surrounds him.

Black Sabbath (1963)

Black Sabbath (I tre volti della paura) (1963) is an episodic horror film directed by Mario Bava under the pseudonym John Old. The film is composed of three separate stories, each with its own setting and cast:

The Telephone: A young woman is persecuted by a mysterious man who throws a knife in her face. The Wurdulak: A man gets involved in a story of vampirism. The Drop of Water: A group of friends goes to a haunted castle.

The Telephone A young woman named Mary (Barbara Steele) is on vacation with her fiancé, John (John Saxon). One night, Mary is awakened by a nightmare in which a man throws a knife in her face.

The Wurdulak A man named Paul (John Richardson) is traveling to meet his fiancée, Elizabeth (Luana Anders). Along the way, Paul meets a woman named Irina (Barbara Steele).

The Drop of Water A group of friends, consisting of a director, a producer, an actor, and an actress, goes to a haunted castle to shoot a horror film.

The film’s most disturbing feature is its set design, particularly the pictorially fantastic interiors. The screenplay and dubbing are above-average methods. The episode “The Drop of Water” is the best of the 3 stories and has been called “Bava’s most frightening work.”

Haxan

Documentary, by Benjamin Christensen, Sweden, 1922.

Desecration of tombs, torture, demon-possessed nuns and witches' sabbath: Haxan, Witchcraft Through the Ages is an incredibly original and unconventional film that has become legendary over time. Between documentary and dramatic fiction, the film guides us through the scientific hypothesis that the witches of the Middle Ages suffered from the same ills as the mentally ill of the modern era. A frightening and at the same time humorous gothic horror, with the creation of documentary and non-fiction sequences that anticipate the innovations of the Nouvelle Vague. Something absolutely unique in the history of cinema.

Food for thought

In Sanskrit Devil and Divine come from the same root, dev. Madness is the dark side of man and it is as natural as the bright side. When you are able to tell a madman that not only is he mad but that you are too, a bridge is immediately created, and it is possible to help him. The nature of life is neither logical nor rational. Life is illogical, wild and contradictory.

LANGUAGE: English, Swedish

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

Onibaba (1964)

Onibaba (1964) is a Japanese horror film directed by Kaneto Shindō. The film tells the story of a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law who survive the 12th-century Genpei War by killing and robbing samurai soldiers. When the daughter-in-law begins a relationship with a deserter, the relationship between the two women is put to the test.

During the Genpei War, a mother-in-law (Nobuko Otowa) and a daughter-in-law (Kei Satō) live in a hut in the middle of a swamp. Their husbands have left to fight in the war, and the two women are forced to survive on their own. To make ends meet, the women kill and rob samurai soldiers who pass through the swamp. They wear masks to hide their identity and leave the bodies in the swamp to be devoured by crabs.

Onibaba is a unique and unforgettable horror film. The film is visually stunning, with atmospheric photography and strong imagery. The performances are all excellent, particularly those of Nobuko Otowa and Kei Satō. The film’s exploration of dark themes is both thought-provoking and disturbing. Onibaba is a film that will stay with you long after you have seen it.

Blood and Black Lace (1964)

Blood and Black Lace (Sei donne per l’assassino) (1964) is an Italian giallo film directed by Mario Bava. The film is set in a fashion house in Rome, where a mysterious killer begins to murder the models. Inspector Silvestri investigates the case but finds himself involved in a game of lies and secrets.

Massimo Morlacchi and Countess Cristiana Cuomo are the owners of a high fashion house in Rome. One of their models, Isabella, is found murdered in her apartment. Inspector Silvestri is called to the scene to investigate the case. Silvestri discovers that Isabella had a relationship with the antique dealer Franco Scalo, who also owns a theater mask that was found near the model’s body. Scalo is interrogated by the police but denies having anything to do with the murder.

Why it is an absolutely must-see horror film: Blood and Black Lace is a classic giallo film, with a compelling plot and a series of ambiguous characters. The film is also known for its murder scenes, which are often violent and splatter. Bava is a master of suspense and thrills, and the film is full of moments that will keep the viewer on the edge of their seat. The film is also visually impressive, with curated photography and detailed production design.

Kwaidan (1968)

Kwaidan (1968) is a Japanese anthology horror film directed by Masaki Kobayashi. It is based on stories from Lafcadio Hearn’s collections of Japanese folk tales, mainly Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1904), from which it takes its name.

Kwaidan is a visually stunning film, with rich cinematography and elaborate set design. It is also a deeply atmospheric film, with a sense of anguish and suspense that pervades every frame. The four stories in the film are all well-told and genuinely frightening, and they stay with you long after the credits have rolled.

Kwaidan was released in Japan in 1964 and in the United States in 1968. It was a critical and commercial success and is now considered one of the greatest Japanese horror films ever made. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1969 and won the Special Jury Prize at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival.

Kuroneko (1968)

Directed by the master Kaneto Shindō, this J-Horror masterpiece reinterprets a classic ghost story from the Heian period through a hypnotic visual aesthetic. The plot follows the tragic fate of a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law who, after being brutally raped and killed by a group of rogue samurai, return from the realm of the dead as vengeful spirits. Bound by a demonic pact, the two entities seduce and massacre passing samurai until their path of blood painfully crosses with the son and husband who has returned from the war, creating a heartbreaking conflict between duty, love, and supernatural horror.

The work stands out for its masterful use of chiaroscuro and atmospheric black and white photography, which gives the spectral appearances an ethereal and theatrical quality, recalling the traditions of Kabuki and Noh theatre. More than a simple horror film, it is a desperate elegance that explores the nature of violence and the pain of loss, profoundly influencing subsequent genre cinema. The tension does not stem from sudden scares but from the construction of an atmosphere of ineluctable sadness and terror, making it an essential cult for fans of auteur cinema.

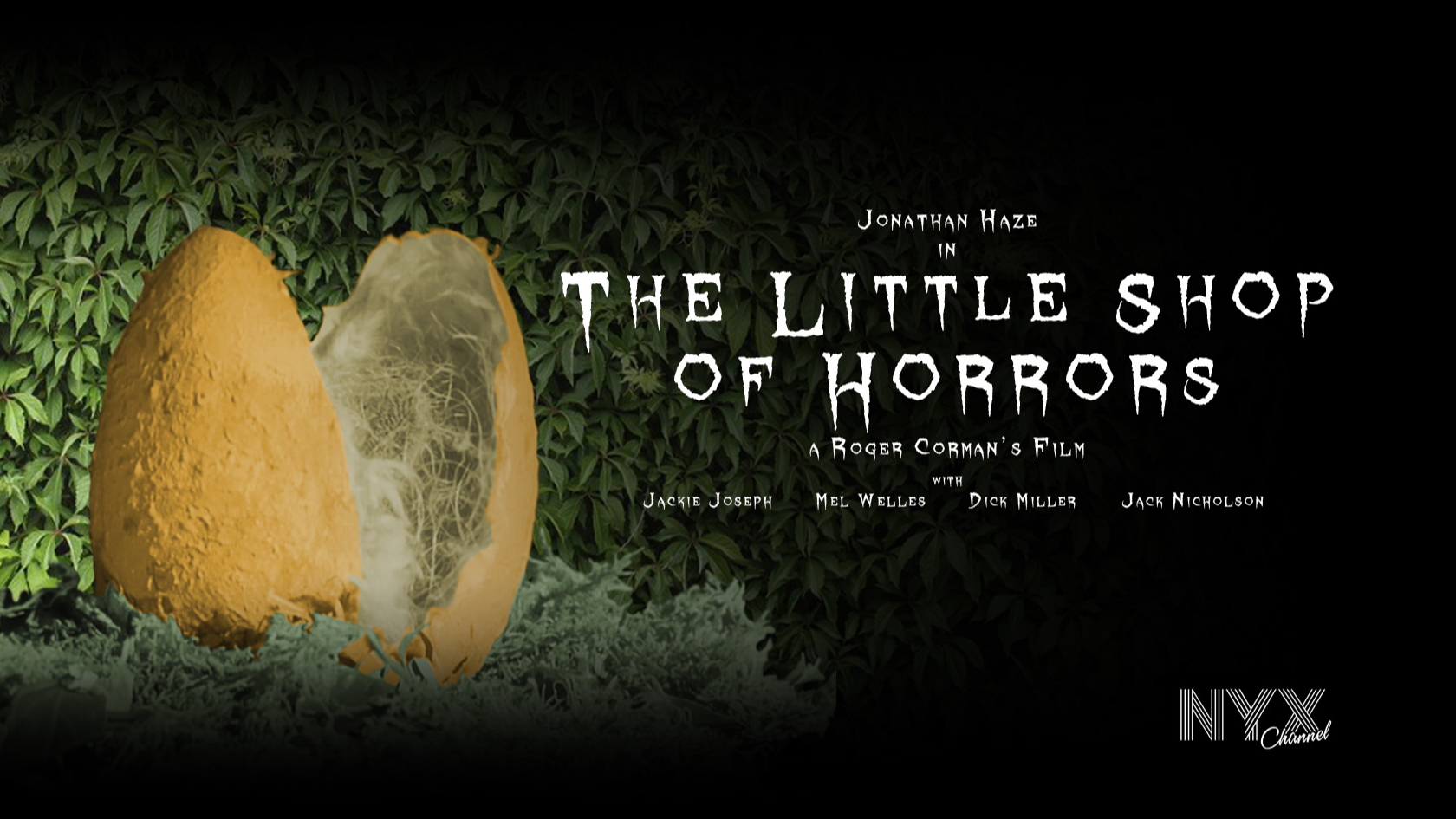

Little Shop of Horrors

Horror, by Roger Corman, United States, 1960.

The brilliant Roger Corman, director and producer who has often worked with ridiculous budgets, allowing the debut of Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Joe Dante, makes the film where his style is more recognizable. A budget of 30 thousand dollars, the exploitation of an existing scenography, two days of shooting, an unprecedented contamination between noir, comedy, horror, surreal and grotesque. Seymour is a shy and clumsy boy, oppressed by a hypochondriac mother, who works as a boy in Mr. Mushnick's flower shop, located in the slums of New York, frequented by rather odd people; his life seems to change for the better when he begins to devote himself lovingly to a strange plant, which he calls the same name as the girl he is in love with. But the plant is not interested in her manure, it just likes human blood. Inspired by the 1932 short story Green Thoughts.

LANGUAGE: english

SUBTITLES: italian, spanish

Hour of the Wolf (1968)

Hour of the Wolf (Vargtimmen) (1968) is a Swedish psychological horror film directed by Ingmar Bergman and starring Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann. The film tells the story of an artist and his wife who retreat to a remote island to work on a new painting, but the artist begins to suffer from strange hallucinations and nightmares.

Johan Borg (Max von Sydow) and his wife, Alma (Liv Ullmann), are artists who retreat to a remote island to work on a new painting. Johan is struggling to find inspiration and begins to have strange hallucinations and nightmares. In his visions, Johan sees a group of mysterious people who are trying to harm him. He also sees Alma, but she is transformed into a terrifying creature.

Hour of the Wolf is a cult classic of horror cinema. It has been praised for its atmospheric photography, its disturbing imagery, and its complex exploration of psychological themes. The film has influenced a number of other horror films, including The Shining (1980) and Dark Water (2005).

Hour of the Wolf is a unique and unforgettable horror film. The film is visually stunning, with atmospheric photography and disturbing imagery. The performances are all excellent, particularly those of Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann. The film’s exploration of psychological themes is both stimulating and disturbing.

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) is an American horror film directed by Roman Polanski and starring Mia Farrow, John Cassavetes, Ruth Gordon, and Sidney Blackmer. The film tells the story of a young couple who move into a new apartment building in New York City and soon find themselves surrounded by strange neighbors and unsettling events. When Rosemary becomes pregnant, she begins to suspect that her neighbors are part of a satanic coven and that they are planning to kidnap her baby.

Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow) and her husband, Guy (John Cassavetes), are a young couple who move into a new apartment building in New York City. The building is owned by an elderly couple, Minnie and Roman Castevet (Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer), and their neighbors are all strange and eccentric. One evening, Rosemary and Guy are invited to dinner at the Castevet’s house. After dinner, Rosemary feels drugged and is raped by a group of people, including Guy.

Rosemary’s Baby is a cult classic of horror cinema. It has been praised for its suspenseful atmosphere, its disturbing imagery, and its exploration of dark themes. The film has influenced a number of other horror films, including The Exorcist (1973) and The Omen (1976).

The Devil Rides Out (1968)

Based on the novel by Dennis Wheatley and scripted by the legendary Richard Matheson, this film represents one of the highest peaks of Hammer production, moving away from the usual Gothic monsters to embrace a high-tension esoteric thriller. The story sees the Duke of Richleau, played by a magnificent Christopher Lee in a rare positive protagonist role, fighting to save the soul of his young friend Simon, who has fallen into the clutches of a satanic cult led by the sinister Mocata. The battle between the two factions soon turns into a duel of wills and ritual magic, culminating in a night of supernatural siege that severely tests the faith and rationality of the protagonists.

The film is considered a classic of British horror cinema precisely for the seriousness with which it treats the theme of occultism, avoiding camp excesses to build a tangible and unsettling threat. Terence Fisher’s direction masterfully manages the narrative pace, balancing action with dense dialogues about the conflict between good and evil. Thanks to a refined staging and artisanal but effective special effects for the time, the work remains a point of reference for the genre, offering a vision of cinematic Satanism that appears simultaneously elegant and terrifying.

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

Barbra and her brother Johnny go to a Pennsylvania cemetery to visit their father’s grave when they are suddenly attacked by a strange, pale man who kills Johnny. Barbra manages to escape to an isolated farmhouse where she finds refuge along with Ben, a resourceful African-American man, and other people hidden in the cellar (the Cooper family and a young couple). While the dead outside return to life hungry for human flesh, inside the house, racial, social, and generational tensions threaten to destroy the group even before the zombies can get in.

With a tiny budget and grainy black and white film, George A. Romero not only created the modern zombie film but also made perhaps the most important political horror film ever. Before this work, zombies were linked to Haitian Voodoo folklore; Romero transformed them into “ghouls,” an anonymous mass of flesh-eaters, an unstoppable force of nature that serves as a catalyst for the collapse of social superstructures. The real threat in the film is not the living dead, who move slowly and awkwardly, but the inability of human beings to cooperate and overcome their prejudices.

Night of the living dead

Horror, di George Romero, Stati Uniti, 1968.

One of the most profitable independent films of all time, it grossed around 250 times its budget. Inspired like other cult horror films by Richard Matheson's 1954 novel "I Am Legend". Shot as a "guerrilla film" with a cast and crew of friends and family and a budget of just $ 114,000, the film is the forerunner of the inexhaustible "zombie movie" genre.

LANGUAGE: english

Horror Movies in the 70s

In the 70s, however, the predominant theme of the horror genre seems to be the demonic possession of children and adolescents. Some titles are Roman Polanski’s Rosemary Baby, William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, Audrey Rose, The Omen. A horror subgenre that will continue in the following decades. The Vietnam War also affects films such as Don’t Open That Door and the Last House on the Left.

The growing phenomenon of consumerism and lifestyle change inspired numerous horror movies, such as David Cronenberg’s The Demon Under Your Skin and George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead sequel Zombie, in which the protagonists are trapped. in a mall.

In Italy the thrill master is Dario Argento. The Italian director makes many high-impact horror movies, exported all over the world. Meanwhile, the young and brilliant directoralso tries his hand at the genre, Brian De Palma creating one of the greatest horror masterpieces in the history of films: Carrie. Even John Carpenter in the late 70s and early 80s will implement several horror. One of them becomes the biggest hit of the slasher genre, a horror sub-starring a group of young people persecuted by a serial killer. This is Halloween.

In 1979 the horror genre returns to merge with science fiction inmasterpiece Ridley Scott’sAlien. Meanwhile, a new fertile production of B series horror movies is born in Europe with Italian directors such as Mario Bava, Lucio Fulci, Ruggero Deodato. Spanish directors such as Paul Naschy, Amando de Ossorio and Jesús Franco. Even the Hong Kong cinema is very prolific in the horror genre.

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970)

It is a 1970 Italian giallo horror film directed by Dario Argento, in his directorial debut. The film is the progenitor of the Italian Giallo cinematic classification.

Dario Argento’s directorial debut marks the birth of the modern Italian thriller, codifying a genre that would dominate the following decade. The protagonist, Sam Dalmas, is an American writer in Rome who accidentally witnesses an assault in an art gallery, remaining trapped between two glass panes while the victim bleeds. Obsessed with the memory of the event and convinced that a crucial detail is escaping him, Sam begins a personal investigation that puts him in the crosshairs of a psychopathic serial killer, while the police fumble in the dark.

The work is a clockwork mechanism that unites Hitchcockian tension with a stylized and visually powerful violence. Argento plays with the viewer’s perception, using visual memory as the key to solving the enigma and building masterful suspense sequences accompanied by Ennio Morricone’s dissonant soundtrack. More than just a giallo, the film is an investigation into the fallibility of the human gaze and urban alienation, characteristics that, combined with innovative and audacious direction, have made it a cornerstone of world cinema.

The Last House on the Left (1972)

It is a 1972 horror film directed by Wes Craven. The film was written by Craven and the plot follows the story of two teenagers, Mari and Phyllis, who are kidnapped by a group of fugitive criminals. During their kidnapping, the girls are subjected to serious physical and psychological violence, including torture and sexual violence.

The criminals, in the end, hide in the house of a couple of parents of the girls, unaware of their presence. When they discover the truth about their guests, parents decide to take revenge on the death of their daughters. The plot is full of twists and turns and intense and disturbing moments, and the film has been considered a social criticism of violence and impunity. However, the representation of violence has aroused many criticisms and has led to numerous disputes. The film was acclaimed as one of the first slasher movie and inspired many other films in the same category.

Images (1972)

Robert Altman ventures into the territory of psychological horror with a complex and visually extraordinary film that explores the fragmentation of the human mind. The protagonist, Cathryn, is a children’s book author who retreats to an isolated country house to work but is soon besieged by increasingly vivid hallucinations of her deceased husband and other unsettling presences. The line between reality and madness progressively dissolves, leaving the viewer and the protagonist unable to distinguish what is true from what is a projection of her fractured psyche.

Thanks to the extraordinary performance of Susannah York (awarded at Cannes) and the innovative photography of Vilmos Zsigmond, the film builds a sense of tangible paranoia, using sounds and images as sensory weapons. It is not a conventional horror film made of scares, but a disturbing drama about identity and schizophrenia, enriched by an experimental soundtrack by John Williams. It is an enigmatic work of art that challenges the viewer to reassemble the pieces of a terrifying mental puzzle.

Nosferatu

When a young real estate agent, Thomas Hutter, goes to the castle to close a deal, Orlok is attracted by his blood and decides to follow him to his hometown. The arrival of the count causes a series of mysterious deaths and spreads panic among the inhabitants.

Murnau, through evocative images and disturbing atmospheres, creates a work that goes far beyond the simple adaptation of Stoker's novel. The film explores universal themes such as the fear of death, isolation and the loss of humanity. The production of Nosferatu was characterized by some legal difficulties due to the copyright of Bram Stoker's novel. Despite this, Murnau and his crew managed to make a film of great visual impact. The choice of Max Schreck to play Count Orlok was ingenious. His cadaverous appearance and his unnatural movements have made the character of Orlok one of the iconic monsters in the history of cinema. Over the years, Nosferatu has become a cult film, influencing generations of filmmakers and becoming a reference point for the horror genre. The image of Count Orlok, with his elongated nails and sunken eyes, has become an icon of horror cinema.

Sisters (1972)

Brian De Palma signs an elegant homage to Hitchcock’s cinema, imbued with voyeurism and psychological obsessions. The story revolves around Danielle, a Canadian model, and her separated conjoined twin, Dominique, whose dark presence seems to haunt her. When a journalist witnesses a brutal murder committed in Danielle’s apartment from her window, an investigation is triggered that brings to light chilling medical secrets and a pathological duality, with the help of a skeptical private investigator.

The film is a triumph of style, characterized by the pioneering use of split-screen which allows following two perspectives of the horror simultaneously, exponentially increasing the tension. The soundtrack by Bernard Herrmann underscores the gothic anguish transported to a modern urban context. De Palma explores themes like the double and the suppression of personality with technical mastery that makes the film not only a compelling thriller but also a visual essay on the nature of looking and being looked at.

The Exorcist (1973)

Directed by William Friedkin, this film forever changed the perception of horror in the mass audience, treating the supernatural with chilling documentary realism. The plot follows the descent into hell of the young Regan McNeil, whose innocence is corrupted by the possession of the demon Pazuzu, and her mother’s desperate struggle to save her. Faced with the failure of medical science and psychiatry, the only hope lies with two priests: the elderly and experienced Father Merrin and the tormented Father Karras, who must confront his own doubts of faith to fight absolute evil.

The film’s strength lies in its ability to build a terror that is as physical as it is spiritual, supported by practical special effects that are still impressive today and a revolutionary sound design. Beyond the iconic and shocking scenes, the work is a profound theological drama about human vulnerability and sacrifice. The oppressive atmosphere and rising tension transform Regan’s bedroom into a universal battlefield between light and darkness, making the film an indelible visual and emotional experience in the history of cinema.

Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein (1973)

This reinterpretation produced by Andy Warhol and directed by Paul Morrissey subverts the Frankenstein myth, transforming it into a grotesque, erotic, and satirical work. The Baron, played with cold madness by Udo Kier, is obsessed with creating a superior Serbian race and assembles two creatures, a male and a female, with the intention of making them procreate. The result is a mix of visceral horror and black comedy, where bodies are treated as cannon fodder and science is merely a pretext for depravity and the delirium of omnipotence.

Originally filmed in 3D to accentuate the “camp” and gore effect, the film stands out for its disrespectful critique of the aristocracy and social conventions. The over-the-top performances and the abundance of explicit scenes make it a unique title in the 1970s horror landscape, capable of disgusting and fascinating at the same time. It is a perfect example of transgressive cinema that uses the monstrous to explore the perversions of power and desire.

Ganja & Hess (1973)

Directed by Bill Gunn, this film is an experimental work of art that uses vampirism as a complex metaphor to explore African-American identity, addiction, and cultural assimilation. The story follows Dr. Hess Green, an anthropologist who becomes immortal and dependent on blood after being wounded with an ancient African ceremonial dagger. His existence intertwines with that of Ganja, his assistant’s wife, in an intense and destructive relationship that challenges the conventions of the traditional horror genre.

Far from being a simple “blaxploitation” film, the work is meditative, visually refined, and accompanied by a hypnotic soundtrack. Gunn deconstructs the vampire myth to talk about religion, sexuality, and the burden of history, creating a film that is both a psychological drama and a dreamlike horror. Misunderstood upon its release, it is now re-evaluated as a visionary masterpiece that transcends genre labels.

Silent night, bloody night

Horror, by Theodore Gershuny, United States, 1972.

1972 American Slasher, is a forerunner horror genre several years before Carpenter's Halloween, with a complex script and first person shooting of the killer, which inspired many subsequent films. Its originality and its narration are what manage to make it a small and little known pearl of the genre. A series of murders in a small New England town on Christmas Eve after a man inherits a family estate that was once a madhouse. Many of the cast and crew members were former Warhol superstars: Mary Woronov, Ondine, Candy Darling, Kristen Steen, Tally Brown, Lewis Love, director Jack Smith, and graduate Susan Rothenberg.

LANGUAGE: english

SUBTITLES: italian, french, spanish

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

Tobe Hooper directs a nightmare on film that defined the aesthetic of rural slasher, based on the idea that true horror resides in human madness rather than the supernatural. A group of friends traveling through Texas ends up crossing paths with a family of cannibalistic former slaughterhouse workers, among whom the iconic figure of Leatherface stands out. What follows is an unstoppable descent into pure terror, where logic and hope are annihilated by the senseless, mechanical brutality of the killers.

The film is famous for its unhealthy, dirty, and suffocating atmosphere, made vivid by grainy photography and disturbing sound editing. Contrary to its fame, it shows very little blood, relying instead on suggestion and the intensity of the performances to shock the audience. It is a fierce critique of the disintegration of the American nuclear family and the dark side of the deep south, a seminal work that transmits a sense of real and tangible danger from the first to the last frame.

Deep Red (1975)

Dario Argento reaches the apex of his artistic expression with this giallo film that is a triumph of aesthetics and tension. The pianist Marc Daly witnesses the murder of a medium and is dragged into a vortex of violent deaths while trying to discover the identity of the killer, whose crimes are linked to a children’s nursery rhyme and a past trauma. The narrative moves between metaphysical architectures and baroque interiors, where every visual detail can be a clue or a deception.

The virtuoso direction, characterized by fluid camera movements and unusual perspectives, blends perfectly with the aggressive and progressive rock soundtrack by Goblin. The film is not just a sequence of elaborate murders, but a sensory experience that explores the fallibility of memory and the omnipresence of the past. With sequences that have become legend and a shocking finale, it remains the absolute reference point for Italian and international thrillers.

Carrie (1976)

Brian De Palma adapts Stephen King’s first novel, transforming it into an operatic tragedy about solitude and revenge. Sissy Spacek delivers a heartbreaking performance as Carrie White, a marginalized teenager bullied by her peers, oppressed at home by a fanatically religious mother. The discovery of her telekinetic powers coincides with the awakening of her sexuality and repressed anger, leading to a devastating climax during the prom that has gone down in cinema history.

The film is a masterpiece of style, using split-screen, slow motion, and saturated colors to emphasize emotion and horror. Beyond the bloodshed, De Palma builds a powerful allegory about the difficulties of adolescence and social cruelty. The final scene is not just a cheap scare but the seal on a psychological drama where the true monstrosity lies in intolerance and fanaticism, making Carrie a tragic and eternal icon.

The House with Laughing Windows (1976)

Pupi Avati signs the masterpiece of “Paduan Gothic,” an atypical horror immersed in the sunlight of the Italian countryside rather than in the darkness. A young restorer arrives in a small village to work on a macabre fresco by a mad painter who died by suicide but soon finds himself enveloped in a web of omertà, threats, and unsettling local legends. The placid, sleepy atmosphere of the province hides perverse secrets and an ancient malice that permeates the entire community.

The film builds tension through unsaid words, silences, and the ambiguous faces of the inhabitants, leading the viewer toward a shocking and nihilistic finale. Avati demonstrates how horror can hide in everyday life and the most familiar places, creating a sense of anguish that never leaves the viewer. It is an unsettling rural giallo that delves into the roots of folklore and human madness with surgical precision.

The Brain That Wouldn't Die

Horror, science fiction, by Joseph Green, United States, 1962.

Dr. Bill Cortner saves a patient who was pronounced dead, but the senior surgeon, Bill's father, condemns his son's unorthodox transplant methods and theories. While driving to his family home, Bill and his attractive future wife Jan Compton are involved in a car accident in which his wife is decapitated. Costs recovers the head and hurries to the laboratory in the cellar of his house. He and his maimed sidekick Kurt revive the head in a tray filled with liquid. Jan's new existence is unbearable and the woman begs Bill to let her die, but the scientist refuses: he wants to find a new body for Jan. He looks for a suitable woman in a burlesque club, on the street and in a beauty contest.

Directed by Joseph Green and written by Green and Rex Carlton the film was finished in 1959 under the title The Black Door, but was not released until May 3, 1962, with its new title as a double feature with Invasion of the Star Creatures . The particular narrative device of a mad doctor who discovers a way to keep a human head alive has been used before in the literature, with various other versions on this theme. It shares numerous story elements with the West German horror film The Head (1959).

LANGUAGE: English

SUBTITLES: Spanish, French, German, Portuguese

Suspiria (1977)

Dario Argento creates a visually overwhelming dark fairy tale, set in a prestigious dance academy in Freiburg that conceals a coven of witches. The young Suzy Bannion finds herself immersed in a world where narrative logic gives way to pure sensory experience: unnatural primary colors, geometric sets, and a Goblin soundtrack that hammers the nerves. It is the first chapter of the Three Mothers trilogy and represents the peak of the director’s visionary style.