There is today a great confusion about what arthouse films are, a discussion that has been going on for more than a century. Is cinema art or entertainment? Great mass show or creation capable of inspiring and improving society? How related are arthouse films and independent cinema? Since the big studios and the propaganda system have conquered the total monopoly of the world cinema audience, cinematographic art has become a cauldron in which to put things that have nothing in common. To understand this concept, first of all we need to understand what art is.

Art is one of the fundamental expressions of the human being and has the precise function of increasing awareness, understanding of invisible and spiritual worlds, revealing the mysteries of life. In every great civilization, such as ancient Rome, Persia, ancient China and India, art has been at the center of society, closely linked to spirituality and political life.

Art and the Development of Civilizations

In ancient Greece, for example, philosophers and artists played a role of fundamental importance: they were true political and spiritual guides who also inspired decisions on the development of daily life. Every evolved civilization has had art among its fundamental points. But when did the annihilation of art in modern history take place?

The passage is evident: the degradation of art occurred when the patrons and producers were no longer individuals with the interest of expanding the consciences of the population. From a tool of spiritual inspiration, art has become an instrument of political and ideological propaganda and has mixed with forms of mass entertainment.

Art-house Films and The Mass Media

Cinema was born in a period of enormous changes in the mental plane of humanity, an era of very rapid development of the mass media. Films are absolutely not born as an art form: at the beginning they present themselves as an extraordinary invention, a physical phenomenon of reproduction of reality. The Lumière brothers in fact used the Cinematograph as a documentary reproduction tool of reality.

George Melies brought cinema to the world of art with imaginative sets and fantastic stories, by hand painting the frames of his short films. But the cinema had not yet managed to shake off that brand of freak, village festival entertainment. A brand that will never be able to take off, at least until today.

What are Arthouse Films?

Returning to the fundamental question, so what are arthouse films? What can be considered cinematographic art and what not? The first big misunderstanding is that the public is now used to considering cinema as a fantastic world where extraordinary budgets are invested and where we see the faces of famous actors, almost mythological beings.

All this obviously has nothing to do with art: the greatest masters in the history of painting and literature have created their works without any budget, simply using their creativity. If you have a lot of money to buy expensive canvases and paints or to buy precious blocks of marble this does not mean that you will paint an extraordinary picture or that you will create a sculpture destined to remain in the history of art.

Most of the great works of art of world literature have been written with a sheet of paper and a pen. The greatest paintings in the history of art were painted with a simple canvas and a brush, and the art market did not attach any value to them. The human being needs a long time to understand what has value and what has no value: very often he makes errors of evaluation. It is often very suggestible, manipulable.

Arthouse Films Are Cinema Art or Entertainment?

The first criticism made of such an argument is that cinema is different from the other arts: it needs technology, a technical crew, famous actors, sets and special effects. It’s not true. It was not true in the days of the Lumière brothers and it is even less true today, when streaming technology allows you to do anything with costs close to zero. The truth is that great ideas, inspiration and creativity can be imposed beyond any budget, any material wealth.

Everything revolves around the vision of the artist, of the filmmakers who with little or nothing can create extraordinary images and stories. If independent cinema often produces things of lesser value than mainstream cinema, the cause is the lack of ideas and vision of independent filmmakers who try to imitate the model of mainstream cinema, in an attempt to become famous and to gain public attention. .

Arthouse Films Are Great Shows and Works of Art?

Mainstream cinema looks a lot like a circus show, a football game, a fireworks display. The art-house film, on the other hand, is something that should be enjoyed with respect and sacredness, as you do when you visit an important museum or an art gallery. The great mass spectacles have a completely different function from art. They have existed since ancient times: the gladiator shows of ancient Rome did not have the function of expanding awareness and civilization, they were only moments of mass excitement and entertainment, a liberating outlet of impulses and emotions.

The propaganda system, very aware of the power of cinematographic art, has transformed films into a means of mass communication, a great liberating entertainment show through which fashions, lifestyles and values of entire society. Cinema is still in its infancy compared to the other millennial Arts: it is like a naïve child who can easily be trapped by more crafty and more experienced individuals.

But the watershed between art film and entertainment film is very simple: the arthouse film serves to expand the awareness of the individual and to evolve civilization, while the great entertainment show serves to excite the masses through emotions and sensations. They are two types of films and two completely different audiences, who have different needs.

What Are Arthouse Films and What Is Their Audience

The viewer of art films, just like the user of works of art, is looking for a higher inspiration, an expansion of his meaning of life. The spectator of entertainment films is looking for escapism, strong emotions, the astonishing stunning of special effects.

This does not mean that the great spectacular film does not have the same dignity and the same need to exist as an art film. It doesn’t mean that an entertainment film can’t also include a certain amount of genuine artistic pursuit. It simply means that the overall vision with which the two types of films were made are completely different and go towards different goals.

Today’s cinematic audience is really confused because even what is considered arthouse cinema by all has been monopolized by the film industry and large film studios. From the first appearances of the great art films in the 1920s, the great film studios understood that that niche, aimed at a certain type of public, was profitable.

Propaganda Cinema

They immediately created special departments for the production of arthouse films with the aim of conquering that particular market. In this way, even the public in search of inspiration ended up in their network, with the possibility of creating thought forms, fashions and lifestyles even for the kind of people who otherwise would not have been interested in their mainstream productions.

90% of what is now considered art cinema is actually produced by the same system that makes entertainment films: perhaps this niche does not make them big gains: the public interested in this search for awareness is limited. . But it allows the great studios to conquer the cultural, philosophical and spiritual leadership of the contemporary world.

The problem is that the same entity cannot pursue such different objectives, which go in diametrically opposite directions. The system’s arthouse films do not have that depth of vision typical of true work of art that offers life-enhancing and inspiration. They are caricatures of the work of art, pale imitations.

The History of Cinema Is What Remains

In the 1920s the great arthouse films were made with limited means by the will of individual filmmakers: the world of cinema was still in great ferment and development, there were dozens of artistic avant-gardes that developed even through movies. Today the films that reach the general public are exclusively the films produced by the system: if you are not in a certain system you do not have the distribution to reach the public.

Time, however, is an merciless judge and cancels all clumsy attempts at false cultural and artistic leadership. Time is like Hamlet’s mill which filters only what is needed and has value. Technology continually creates new scenarios that make old systems based on market monopoly fail. Cinema is no exception: streaming has democratized the ability to distribute films around the world.

But what is the definitive answer to the question “what are arthouse films?”. The answer is that an arthouse film is a work of art that provides inspiration and the search for truth to the individuals and societies that are seeking it. Individuals and societies who do not seek them, who instead seek leisure, entertainment and strong emotions, do not evolve, and are destined for constant regression. This is what has been happening for some centuries, especially in the West. Fortunately, somewhere, there are individuals who go the opposite way, and they will take charge of dragging the heavy ballast.

What Happened to Arthouse Cinema?

The history of cinema, in particular that of arthouse cinema, is a complex history like that of the other Arts and more generally like the history of humanity. It has been subject to many pitfalls, misleading ways of thinking, as well as being full of creativity and genius. Art cinema is often closely related to independent cinema and rarely finds space in large industrial productions, often forced to please the public with a more standardized language to maximize profits and reduce the risk of production.

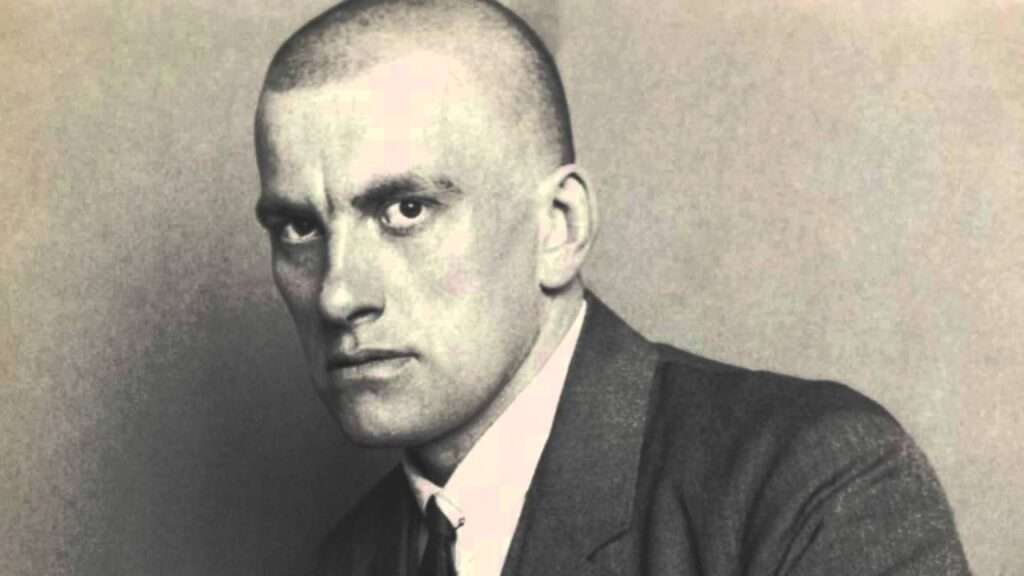

Mayakovsky already in the 1920s had hit a fundamental point not only of cinema, but of human society as a whole.

For you, cinema is entertainment.

For me it is almost a

conception of the world.

Cinema is the bearer of movement.

Cinema modernizes literature.

Cinema demolishes aesthetics.

Cinema is audacity.

Cinema is an athlete.

Cinema is the diffusion of ideas.

But the cinema is sick. Capitalism threw a handful of gold in his eyes. Skilled entrepreneurs take him for a walk through the streets, holding him by the hand. They collect money, moving people with petty tearful subjects.

This must end.

Communism must take cinema out of the hands of speculators.

Futurism must evaporate dead waters: stagnation and moralism.

Without this we will have either the American-imported tip-tap, or the only “teary eyes” of the various Mogiuchin.

The first of these two possibilities has bored us.

The second even more.

If you try to replace cinema with life in this poem by Mayakovsky you will get an even more powerful effect, which further broadens his critique. In fact there is not a big difference between cinema and life, cinema is the mirror of life.

These words of Mayakovsky acquire even more meaning considering his history, and the regime in which he lived. Mayakovsky, however, hits a point that goes even further beyond the limited freedom of totalitarian regimes. It is about the manipulation of art and the media for political, ideological and commercial purposes, through which, in apparently democratic societies, it is possible to shape people’s way of thinking in an occult way.

The Decline of True Arthouse Films

The great collapse of arthouse cinema began more or less at the end of the seventies with the overwhelming assertion of television. Television has been the medium capable of influencing the masses around the world for 50 years.

Television began its broadcasts taking inspiration from cinema and maintaining a high quality audiovisual language for more than twenty years. With the arrival of commercial television, the language of images gradually deteriorated until it became a crazy schizophrenic supermarket.

Funny and hilarious Federico Fellini’s point of view in the 80s when he shoots films as an interview with Ginger and Fred where television is a kind of mellstrom that advances by incorporating everything, in a kind of great phenomenon of collective hysteria.

Fellini, in his masterpiece book Making a film, recounts that when he turned on the television he had the impression of connecting live with a mental hospital: the sadism of the telequiz presenters in torturing the sweat-dripping competitors, processions of semi-naked girls dressed like chickens, insane and cynical idiocy of commercials.

Fellini’s gaze was the pure gaze of a brilliant man, and he was able to grasp this madness that most people missed. The others invented excuses, society is changing and progress must be accepted. But intellectuals of the caliber of Fellini and Pier Paolo Pasolini did not believe these lies: they clearly saw the emergence of a kind of madhouse on a global level.

Today talking about this after 50 years of live broadcasts in our homes is simply absurd: madness has become the world we live in. But it would be enough to read Fellini’s book and make a film to completely overturn our vision.

Arthouse Films and Social Changes

But is it simply the evolution of society and the tastes of the public or is it something deliberate? In my opinion it is something deliberate: it is a systematic planning for the destruction of art cinema, almost completely replaced by products that can be useful for achieving certain purposes. Commercial purposes, of course, but above all spiritual purposes, of interior impoverishment of the masses.

Commercial purposes? Sure, but that’s not the main thing. The real interest lies in profoundly influencing the way people think and feel. Cinema has lost its dominance in the media world, but the big screen is still pivotal in creating ways and lifestyles around the world. To influence the spirit of the human being.

Through the means of propaganda it simply means imposing mediocre and untalented characters and building an artistic phenomenon upon it, planning any useful strategy. That’s what’s coming from the 1980s onwards. It is a phenomenon that today covers at least 90% of film productions.

They are all the projects and characters created at the table, without a real inner value, but touted as great artistic phenomena destined to change the consumption of films, The consumption of art. They are puppets, just as parades of carnival floats are the places dedicated to their promotion.

Honestly, it seems to me that it is not difficult to perceive this, because after all it is a widespread feeling among many people. But it is something that remains buried in the unconscious, that one cannot admit even to oneself.

Arthouse Cinema as Entertainment

The concept of entertainment, created perfectly in the United States of America and then spread to the rest of the world, has been progressively affirming itself. The directors of the 1920s who worked alongside the painters of the avant-garde movements would not have understood at all.

The Lumière and Méliès brothers, who had shown the films at village fairs, could have understood the concept of entertainment. But they would have wondered: isn’t cinema now evolving towards something higher?

Start watching movies with your free trial now

The Golden Age of Arthouse Films

The 1920s were the most radical period in thinking about cinema as an art, with the support of the world of painting and with the revolutionary theories of Soviet editing. A mix of figurative art and musical rhythm that has given the cinema explosive potential. But soon after, in the 1930s, the concept of entertainment established itself together with the birth of Hollywood.

Another great period for cinema as an art was that of the 1960s. From the French New Wave to great authors around the world, films had a magical moment, in which thousands of works of art were created.

Jean Luc Godard is perhaps today the last of the true innovators of cinematographic art. Jean-Luc Godard would never make a series for streaming channels like Scorsese, Sorrentino and many other arthouse film directors did. Jean Luc Godard is another of the giants of the history of cinema and art who witnesses from the height of his 90 years to a distortion of the incomprehensible cinematographic language, reduced to an unprecedented homologation.

Jean-Luc Godard and hundreds of other film makers of that era used cinema to create new forms of art. In the 1920s, directors were inspired by Futurism, Expressionism and Impressionist painting to create their works. In fact, seeing a film from that era or seeing a Nouvelle Vague film is a bit like entering an art gallery.

Why Ghettoize Arthouse Films?

Then came entertainment. But why is this so powerful statement nowadays absolute of cinema as entertainment? I could put forward this hypothesis. Entertainment is about thrilling the audience, not transforming and elevating their view of the world. Maybe we need to make sure that people remain like children on a roller coaster?

The viewer gets excited, frightened, has fun, produces adrenaline, comes out stunned and satisfied by the cinema, as if under the influence of a good drug, and it all ends there. The art film, on the other hand, can change your life and expand in you a new, more conscious vision of the world. But the discussion does not end there. There is a need to make the public believe that a certain type of audiovisual products are art, by celebrating and advertising them in every possible way.

By accustoming the public to the amusement park carousel, it can be stunned and made more and more unaware. The visual art and the rhythm of the vision for the average cinema viewer does not matter: he is looking for adrenaline for an evening of strong emotions. But there is always a small niche of people who do not believe in certain nonsense and remain in search of the art film. How to deal with these stubborn ones?

The Fake Arthouse Films

Simple: we invent the fake arthouse cinema. We create a series of characters through famous awards and media advertising that fit into a certain design. Which design? Political, commercial? Also but above all a plan of spiritual zeroing. Through these famous and award-winning authors, passed off as great artists, almost no opening must arrive. The discourse must remain in the matter, in politics, in a certain ideological vision. In this way, a society is shaped with false myths and new fashions, according to what those in power deem appropriate.

But isn’t there the democratic distribution of the internet and the great possibilities of accessing any content today? Yes there is, but the public is missing. The public does not have the capacity and the critical spirit to choose with their own head, beyond any advertising influence, any award, any celebration.

Have you ever gone to a starred restaurant that appears in the prestigious gastronomic guide and eat crap? It actually happens very frequently. What is said about that place does not correspond to the perception of your taste buds. But I’m willing to bet 99 out of 100 people will ignore it while dining with friends. They won’t believe their taste buds. If everyone says it is, it probably is.

Critical awareness of the perception of a work of art is practically the same thing. If everyone talks about that particular film, if everyone celebrates it, if he wins many awards, if the director is famous, even if he doesn’t convince me, it’s probably a great work of art. The critical spirit is an endangered matter. Since I don’t have it, I adapt to what the experts say, so I also make a good impression on my alternative friends.

The Experts of Arthouse Films

For the average viewer, there is simply no alternative: what we are talking about, what everyone is talking about, what the expert is talking about is Cinema with a capital C. The alternatives therefore exist, but the average viewer is deaf and blind: they respond only to the stimuli that come from advertising and media noise. With such an audience it’s easy to drive the carousel – just press the button to start it and wait. Everything happens automatically.

Immediately you find a multitude of people ready to say that times are changing that we must accept the evolution of things. Nonsense. These people have a poor understanding of what is going on around them. The truth is that if governments and the media had promoted true arthouse cinema over the decades we would now have a completely different, more aware society. A society made up of people that are more difficult to manipulate. Because this is precisely the function of art, and cinema, done in a certain way, is art.

The destruction of art cinema, or rather its mystification into products that have nothing to do with art, was deliberate. All other arts were also demolished. Do you often hear dialogues between friends or at the tables of a bar about painting that has spanned the centuries? On the great literature. If you’re lucky you can hear a conversation about the latest talentless fashion cartoonist launched by the mainstream media: another, yet another mystification, of talent and art.

Arthouse Films Can Change

There are paintings that alone could change people’s lives and lead them to a much broader understanding of the existence they live. But they are works totally ignored and deliberately hidden by the system. Do you know for example the paintings of Courbet, and his two fundamental works that have marked the development of history, such as L’origin du Monde, and Bonjour Monsieur Corbet? Probably not, yet due to their impact these works should be disseminated through schools and the media.

But the problem is still the same. The great works of art are the means by which the awareness of the human being is raised, one of the fundamental functions of art.

Now try to imagine some small changes in the evening programming of TV, on streaming platforms and in cinemas. A program that introduces young people and the general public to the great artists of the cinematographic art.

At first, after decades of garbage, the average viewer would be stunned and bored. We would go to take refuge in the kitchen and browse the refrigerator, while a film by Antonioni is shown on the national channel. But already after a few days, when his schizophrenic brain activity subsides, he may devote himself to observing and trying to understand this strange language.

After a few weeks, many will have understood it and will begin to appreciate it. After a few months or years, many will realize that this can change their life, and that they have been subjected to an avalanche of garbage for years. Let’s also assume, absurdly and out of pure madness, that there is someone who knows and loves these films and who presents them with his expertise, on prime-time TV instead of the telequiz and reality show. Or that there is a debate after the film in which the important issues dealt with are deepened. How long would it take to initiate a radical change in society. Not very much.

Then imagine that these films are taught in school along with other great works of art that are ignored by the school curricula. Children much more receptive than adults would take even less time to change their perception of reality. Because reality is not something objective, what we perceive is us. We are the ones who create reality. Unknowing people who ignore this let the mainstream media create reality, leave the creative power of thought to those who dominate the system. And the system thinks about your existence for you.

The Arthouse Cinema and the Multiplex Society

But immediately you find many people who contest this type of discourse saying: But is cinema so important? Yes, it is important because cinema is the mirror of life, and different visions create different versions of the world. It is we who create the world we live in. If there are people who believe that everything is a huge supermarket, who have built neighborhoods and entire cities that are gigantic shopping centers, who want to transform humans into an animal that produces, consumes and cracks, this is their problem. And it also becomes a problem for us when we leave the house and instead of finding a civilization we find an endless desert of special offers.

After all, who cares, it’s a pastime, it’s entertainment. After all, what is the importance of art, if not spending a few hours in a museum contemplating images? These statements correspond exactly to what they wanted to build in recent decades: a society without the ability to observe and contemplate, without awareness, poor in spirit. A company that loves to enjoy, ride the roller coaster of the Luna Park. Who believes only in what is touched by hand.

Too bad that all he is allowed to touch with his hand is a piece of plastic, and that there is someone who thinks his life for him. But that societythat broadcasts arthouse films in prime time, and shows with an in-depth debate the origin of Courbet’s du Monde, where it is. It’s around the corner, in an invisible world. Achievable with a few necessary changes.

100 Arthouse Films to See

Here is a list of 100 must-see arthouse films for any lover of art cinema, accompanied by brief descriptions:

The Seventh Seal (1957)

“The Seventh Seal” is a film directed by Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, released in 1957. It is considered one of the masterpieces of auteur cinema and has had a significant impact on the history of film. The original title in Swedish is “Det sjunde inseglet.”

The film is set in the 14th century during the plague epidemic in Europe. The story follows the knight Antonius Block and his squire Jöns as they return to Sweden after the Crusades. During their journey, the knight finds himself in a deep state of spiritual crisis and doubt about life, death, and the existence of God. Block decides to challenge Death to a game of chess, seeking to gain time to uncover the meaning of life and faith.

“The Seventh Seal” is a film rich in philosophical and religious themes. Through the knight and other characters they encounter on their journey, Bergman explores the meaning of human existence, faith, death, and inner struggle. The film presents a profound reflection on the human condition, doubt, and the search for meaning in a world marked by suffering and death.

One of the distinctive elements of the film is its visual and symbolic representation. The use of light, shadow, and set design creates a surreal and evocative atmosphere that emphasizes the existential issues at hand. The image of the knight playing chess with Death has become a cinematic icon, representing humanity’s struggle against the forces of the unknown.

“The Seventh Seal” is an example of auteur cinema that stands out for its conceptual depth, visual style, and how it addresses universal existential themes. The film has influenced numerous directors and left a lasting imprint on the history of cinema, contributing to the elevation of Swedish cinema and Bergman to international recognition.

La Dolce Vita (1960)

“La Dolce Vita” is a 1960 Italian film directed by Federico Fellini. It’s considered one of the most iconic and influential films in the history of cinema, and it played a significant role in shaping the concept of “paparazzi culture.” The title translates to “The Sweet Life” in English.

The film follows the life of Marcello Rubini, a journalist played by Marcello Mastroianni, as he navigates through the vibrant and hedonistic social scene of Rome. Marcello is torn between his desire for a meaningful existence and his immersion in the superficial and often decadent world of the rich and famous. The movie is structured as a series of episodes, each portraying Marcello’s encounters with various characters and his experiences within the glamorous, yet ultimately empty, world he inhabits.

Fellini uses Marcello’s journey as a lens to explore the societal changes and moral dilemmas of post-war Italy. The film delves into themes of existentialism, alienation, celebrity culture, and the search for authentic human connections. The title itself reflects this juxtaposition between the allure of the extravagant lifestyle and the existential emptiness that Marcello and many of the characters experience.

“La Dolce Vita” is renowned for its captivating visuals, striking black-and-white cinematography by Otello Martelli, and its ability to capture the essence of a particular era and atmosphere. The famous scene with Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain has become an enduring image in cinematic history.

The film was both praised and criticized upon its release. It won the Palme d’Or at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival and received several Academy Award nominations, including Best Director and Best Original Screenplay. However, its portrayal of certain aspects of society was also controversial, leading to debates about its moral and social implications.

“La Dolce Vita” remains a classic and continues to be analyzed and celebrated for its commentary on modernity, celebrity, and the human condition. It marked a pivotal moment in Fellini’s career and had a profound impact on international cinema, inspiring generations of filmmakers and leaving an indelible mark on popular culture.

Rashomon (1950)

“Rashomon” is a Japanese film released in 1950, directed by Akira Kurosawa. The title “Rashomon” refers to the name of a city gate in Kyoto, but it has become synonymous with a phenomenon where different people have conflicting and self-serving accounts of the same event. The film is often credited with introducing Japanese cinema to the international stage and remains a classic example of storytelling innovation.

The film’s narrative structure is groundbreaking. It presents the same incident – the rape of a woman and the murder of her husband – from multiple perspectives, as recounted by various characters involved in the event. As each character tells their version of the story, the audience is exposed to the subjectivity of human memory, perception, and truth. The accounts of the incident are contradictory and reveal how each character’s personal biases and motivations shape their version of events.

“Rashomon” explores the nature of truth, the complexity of human behavior, and the ambiguity of morality. The film raises questions about the reliability of eyewitness testimony and the elusive nature of objective reality. It challenges the idea that there is a single, objective truth and highlights the malleability of perception.

The film’s visual style, cinematography, and use of weather to reflect the characters’ emotional states are notable aspects. Kurosawa’s direction and Toshiro Mifune’s performance as the bandit are particularly lauded. The film’s impact on world cinema was significant, and it won several awards, including the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, which helped introduce Japanese cinema to a global audience.

“Rashomon” is celebrated for its exploration of philosophical and psychological themes, as well as its innovative narrative structure. It has influenced countless films and filmmakers, and its legacy continues to resonate in discussions about truth, memory, and storytelling.

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

“Once Upon a Time in the West” is a 1968 Italian-American epic Western film directed by Sergio Leone. The title in Italian is “C’era una volta il West.” The film is often considered one of the greatest Westerns ever made and a classic in the genre. It is known for its sweeping visuals, memorable characters, and iconic score composed by Ennio Morricone.

The film’s narrative revolves around a complex and intertwining storyline. It follows several characters whose lives become entangled as they converge on a piece of land in the American West. The story involves a widow named Jill McBain (played by Claudia Cardinale) who inherits her murdered husband’s land, a mysterious harmonica-playing gunslinger named Harmonica (played by Charles Bronson), a cold-blooded outlaw named Frank (played by Henry Fonda), and a notorious bandit named Cheyenne (played by Jason Robards).

“Once Upon a Time in the West” is renowned for its meticulous attention to visual details, the use of long takes, and the deliberate pacing that builds tension throughout the film. Sergio Leone’s signature style, characterized by close-ups, wide shots, and the juxtaposition of silence and explosive action, is on full display. The film’s epic scope and operatic quality evoke a sense of mythic storytelling.

Ennio Morricone’s score for the film is considered one of the greatest in cinematic history. The haunting melodies and atmospheric compositions contribute significantly to the film’s mood and emotional impact.

Beyond its stunning cinematography and score, the film explores themes of greed, vengeance, and the impact of progress on the Old West. It plays with genre conventions, deconstructing and subverting Western archetypes. The film’s visual storytelling, character-driven narrative, and use of silence add depth and complexity to the traditional Western formula.

“Once Upon a Time in the West” has left a lasting legacy and continues to be celebrated for its artistic achievements. It has influenced numerous filmmakers and is a quintessential example of Sergio Leone’s distinctive approach to filmmaking within the Western genre.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

“2001: A Space Odyssey” is a 1968 science fiction film directed by Stanley Kubrick. The Italian title of the film is “2001: Odissea nello spazio.” The movie is considered a masterpiece of cinema and an iconic work within the science fiction genre. It is based on a short story by Arthur C. Clarke titled “The Sentinel.”

The plot of the film is divided into four parts that cover various key moments in human history and space exploration. The story begins with “The Dawn of Man,” where ancient hominids encounter a black monolith that appears to influence their intellectual development. This monolith recurs throughout the film, symbolizing a mysterious and powerful entity.

The second part, “TMA-1,” follows a group of astronauts on the moon as they investigate a buried monolith. This event leads to an epochal shift in humanity and the launch of a space expedition to Jupiter aboard the spacecraft Discovery One. Onboard the ship, the supercomputer HAL 9000 becomes a crucial character, leading to tensions and disruptions within the crew.

The third part, “Jupiter Mission,” follows astronaut Dave Bowman as he travels to Jupiter, guided by the presence of the monolith. During this journey, Bowman experiences strange and surreal events that lead him to a transcendent experience beyond human understanding.

“2001: A Space Odyssey” is renowned for its extraordinary cinematography, cutting-edge special effects (considered groundbreaking for its time), and the evocative musical score by Richard Strauss and György Ligeti. The film is known for its use of suggestive imagery, extended visual sequences, and its experimental approach to storytelling.

Kubrick created a cinematic experience that invites viewers to reflect on profound themes such as human evolution, artificial intelligence, the meaning of existence, and humanity’s role in the universe. “2001: A Space Odyssey” is a film that continues to be admired for its futuristic vision and its ability to stimulate philosophical and interpretive discussions.

The Godfather (1972)

“The Godfather” is a 1972 crime drama film directed by Francis Ford Coppola. The Italian title of the film is “Il Padrino.” Based on the novel of the same name by Mario Puzo, the film is widely regarded as one of the greatest movies in cinematic history and is a landmark in the gangster genre.

The story revolves around the powerful Italian-American Mafia family led by Vito Corleone, portrayed by Marlon Brando. The patriarch’s desire to keep his family out of the drug trade creates tension and conflict with rival gangs. Michael Corleone, played by Al Pacino, is initially uninvolved in the family’s criminal activities but becomes drawn into the world of organized crime as he seeks to protect his family’s interests.

The film is known for its iconic performances, intricate plot, and memorable quotes. It explores themes of power, loyalty, family, and the American Dream. “The Godfather” is notable for its rich character development, complex relationships, and a blend of intense drama and moments of violence.

The film’s success led to the creation of two sequels, “The Godfather Part II” (1974) and “The Godfather Part III” (1990), which further explored the Corleone family’s history and legacy.

“The Godfather” has had a lasting impact on popular culture and has been praised for its direction, writing, acting, and cinematography. It has been the subject of analysis and discussion among film scholars and enthusiasts alike, and its influence on subsequent films and television series is profound.

Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

“Once Upon a Time in America” is an epic film from 1984 directed by Sergio Leone. This crime drama is renowned for its length, narrative complexity, and thematic depth.

The plot follows the lives of a group of young Jewish gangsters in 20th-century New York, focusing particularly on two childhood friends, David “Noodles” Aaronson (played by Robert De Niro) and Maximilian “Max” Bercovicz (played by James Woods). The storytelling shifts between various time periods, alternating between the past and the present, as it unveils their stories, from young delinquents to established gangsters and beyond.

The film explores themes such as friendship, organized crime, social ascent, love, and betrayal. “Once Upon a Time in America” is a dense and ambitious work that provides a deep immersion into the lives of its protagonists and the evolution of their relationship over the decades. Ennio Morricone’s soundtrack significantly contributes to creating the film’s emotional and nostalgic atmosphere.

Director Sergio Leone is known for his distinctive visual style, which incorporates long tracking shots, iconic framing, and meticulous attention to detail. This film represents an evolution in his style, moving away from spaghetti westerns to embrace a more intimate and dramatic narrative.

“Once Upon a Time in America” received mixed reactions upon its release, but over the years, it has grown in reputation and is considered one of the finest films of its era. The director’s original version, with a runtime of over four hours, has since been restored and released, garnering further praise for its complexity and depth.

Blade Runner (1982)

“Blade Runner” is a science fiction film released in 1982 and directed by Ridley Scott. The film is a visually stunning and thought-provoking exploration of artificial intelligence, identity, and the blurred lines between humanity and technology.

Set in a dystopian future Los Angeles in 2019, the story follows Rick Deckard (played by Harrison Ford), a “Blade Runner,” a specialized police officer tasked with hunting down and “retiring” replicants, which are bioengineered human-like androids created for various purposes. As Deckard delves deeper into his mission, he begins to question the nature of humanity and the moral implications of his actions.

The film is known for its visually striking and immersive depiction of a future world, featuring a blend of cyberpunk aesthetics and film noir elements. The towering cityscapes, rainy streets, and neon-lit signs contribute to the film’s unique atmosphere.

“Blade Runner” raises philosophical questions about what it means to be human and the ethical considerations surrounding the creation of artificial life. The replicants in the film, despite being engineered, exhibit emotions, memories, and desires that challenge traditional notions of humanity.

The film’s intricate narrative, philosophical themes, and stunning visual effects have made it a cult classic and a significant influence on the science fiction genre. Over the years, “Blade Runner” has been re-released in various versions, including Ridley Scott’s director’s cut and the final cut, allowing audiences to explore different iterations of the film and its complex themes.

The Night (1961)

“La notte” is an Italian drama film from 1961 directed by Michelangelo Antonioni. The film is part of Antonioni’s “Incommunicability Trilogy,” alongside “L’avventura” (1960) and “L’eclisse” (1962). “La notte” is an emblematic example of auteur cinema and played a significant role in solidifying Antonioni’s reputation as one of the most influential directors of his time.

The film’s plot unfolds over the course of a single day and follows a day in the life of a renowned writer, played by Marcello Mastroianni, and his wife, played by Jeanne Moreau. The couple appears to lead a comfortable bourgeois life, but their marriage is marked by increasing alienation and lack of communication. The film explores the emotional tensions and internal conflicts of the two protagonists as they attend a fashionable party in Milan.

“La notte” is notable for its visual representation of emotions and isolation through the use of urban landscapes and empty spaces. Antonioni employs long takes and dialogue-free sequences to highlight the characters’ loneliness amidst the crowd and to underscore their lack of connection with each other.

The film delves into themes such as alienation, disillusionment, and the difficulty of human connection in a modern society. The night of the party becomes a metaphor for the emotional emptiness and inner isolation of the main characters, underscoring a distrust of traditional social bonds.

“La notte” is widely recognized for its sophisticated direction, evocative cinematography by Gianni Di Venanzo, and the intense performances of its actors. The film was critically acclaimed and has had a lasting impact on auteur cinema and filmmaking as a whole.

Persona (1966)

“Persona” is a Swedish film from 1966 directed by Ingmar Bergman. This film is considered one of the director’s masterpieces and a milestone in auteur cinema and psychological exploration.

The plot follows the interaction between two women: Elisabet Vogler, an actress who suddenly stops speaking, and Alma, a nurse assigned to take care of her in an isolated house by the sea. Over the course of the film, a complex psychological interplay emerges between the two women, in which their identities and personalities seem to overlap and mutually influence each other.

Bergman uses “Persona” to delve into profound themes such as identity, communication, the duality of the human soul, and the intricate nature of interpersonal relationships. The film employs a distinctive visual approach, with scenes that play with the viewer’s perception through the use of editing, superimposed images, and dreamlike imagery.

The narrative is characterized by a series of internal monologues, intense dialogues, and moments of eloquent silence. The performances of the two lead actresses, Bibi Andersson in the role of Alma and Liv Ullmann in the role of Elisabet, are remarkably deep and complex, contributing to the creation of an emotionally engaging atmosphere.

“Persona” is often regarded as one of the most influential films in the history of Swedish and world cinema. Its experimental structure and universal themes have made it a subject of study and analysis by critics, scholars, and cinema enthusiasts.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

“Apocalypse Now” is a 1979 American film directed by Francis Ford Coppola. This film is an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novella “Heart of Darkness” and is set during the Vietnam War. It is known for its powerful depiction of the psychological and moral complexities of war.

The story follows Captain Benjamin L. Willard, played by Martin Sheen, who is tasked with a dangerous mission: to locate and “terminate with extreme prejudice” Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, played by Marlon Brando, a highly decorated officer who has gone rogue and established his own private army deep within the Cambodian jungle.

The film explores the brutality and insanity of war, as well as the blurred lines between good and evil in the context of conflict. It delves into the psychological impact of war on soldiers and the dehumanizing effects of violence. “Apocalypse Now” is known for its haunting visuals, intense performances, and memorable sequences, such as the iconic helicopter assault set to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.”

The production of the film was notoriously challenging, plagued by setbacks, budget overruns, and adverse filming conditions. Despite these difficulties, the film became a critical and commercial success, earning multiple Academy Award nominations and leaving a lasting impact on cinema.

“Apocalypse Now” is often hailed as a landmark in war cinema, exploring themes of morality, imperialism, and the human psyche in the midst of chaos and destruction. It remains a thought-provoking and enduring work that continues to captivate audiences and spark discussions about the nature of war and humanity’s capacity for darkness.

Barry Lyndon (1975)

“Barry Lyndon” is a 1975 film directed by Stanley Kubrick. It is an adaptation of the novel “The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon” by William Makepeace Thackeray. The film is renowned for its exquisite visual beauty and meticulous historical detail in depicting 18th century Europe.

The plot follows the life of Redmond Barry, a young Irishman with social ambitions, who seeks to climb the European social ladder through wit and deception. After a series of adventures and romantic intrigues, Barry becomes Barry Lyndon after marrying a wealthy heiress. However, his rise is followed by a fall, and the film explores themes of luck, vanity, ambition, and morality.

One of the most striking aspects of “Barry Lyndon” is its extraordinary cinematography, utilizing abundant natural light and painterly techniques reminiscent of the 18th century. The film also features a soundtrack composed of classical pieces from the era, creating an authentic atmosphere.

Although the film did not achieve significant box office success upon its release, it has been reevaluated over the years and is widely regarded as one of Kubrick’s masterpieces. Its meticulous visual representation and in-depth characterization of the characters contribute to making it a highly impactful work. “Barry Lyndon” exemplifies auteur cinema, standing out for its unique style, attention to detail, and the ability to transport audiences to a bygone era with timeless visual beauty.

La strada (1954)

“La Strada” is a 1954 film directed by Federico Fellini. This film is a masterpiece of Italian neorealistic cinema, telling a poignant story of hope, despair, and redemption.

The plot follows Gelsomina, a naive and simple young woman played by Giulietta Masina, who is sold by her mother to Zampanò, a traveling performer played by Anthony Quinn. Zampanò is a rough and brutal man who performs a circus act by breaking chains and iron bars. Gelsomina accompanies him on his journey, facing the hardships of a wandering life and the harsh reality together.

The film explores themes of loneliness, empathy, and humanity through the contrast between Gelsomina, with her innocence and kindness, and Zampanò, with his indifference and violence. Their complex and often painful relationship becomes an exploration of human nature and different forms of bonding and love.

“La Strada” is known for its sensitive direction and Giulietta Masina’s emotive performance, which earned her the Best Actress award at the Cannes Film Festival. The film captures the stark and raw atmosphere of post-war Italy and offers a deep insight into the hearts and minds of its characters.

This film has left a lasting imprint on the history of cinema and helped solidify Fellini’s reputation as one of the great directors of his time. “La Strada” stands as an example of auteur cinema that transcends linguistic and cultural barriers, touching the emotional chords of an international audience with its universal story of hope and humanity.

Taxi Driver (1976)

“Taxi Driver” is a 1976 film directed by Martin Scorsese. It is a gritty and psychological drama that delves into the dark and seedy underbelly of New York City.

The film follows Travis Bickle, portrayed by Robert De Niro, a Vietnam War veteran who becomes a taxi driver in the city. As he navigates the streets of New York, he becomes increasingly disillusioned with the urban decay, crime, and corruption he encounters. Travis’s isolation and growing mental instability lead him down a path of obsession and violence.

“Taxi Driver” explores themes of loneliness, alienation, and the search for purpose in a harsh and unforgiving world. Travis’s descent into madness is portrayed with intense and haunting realism, thanks in part to Robert De Niro’s powerful performance. The film also examines the themes of urban decay, mental illness, and the blurred lines between heroism and villainy.

The movie’s gritty visuals, atmospheric score, and Scorsese’s direction contribute to its iconic status in the history of cinema. “Taxi Driver” is often celebrated for its exploration of the darker aspects of the human psyche and its unflinching portrayal of urban life. It has become a defining film of the 1970s and is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made.

Raging Bull (1980)

“Raging Bull” is a 1980 film directed by Martin Scorsese. It is a dramatic biographical movie that tells the story of Italian-American boxer Jake LaMotta.

The film stars Robert De Niro in the role of Jake LaMotta, a boxer with a violent and self-destructive temperament. The story follows his career in the world of boxing, focusing on his rise, fall, and eventual redemption. While LaMotta achieves success in the ring, his life outside the ring is marked by personal issues, family conflicts, and self-destructive behavior.

“Raging Bull” is known for its raw and realistic portrayal of violence in boxing, as well as its deep analysis of LaMotta’s internal conflicts. The film explores themes of jealousy, anger, toxic masculinity, and the struggle for self-control. LaMotta is a complex character, often hard to love, but his vulnerability and contradictions are depicted in a raw and authentic manner.

Scorsese’s direction stands out for its innovative use of camera work and editing, creating an emotionally engaging narrative. De Niro’s performance is considered one of his best and earned him an Academy Award for Best Actor.

“Raging Bull” is much more than a mere boxing film: it is a profound exploration of human psychology, the road to self-destruction, and the search for redemption. The film is regarded as one of Scorsese’s masterpieces and one of the greatest films of all time.

Ran (1985)

“Ran” is a 1985 film directed by Akira Kurosawa. It is a Japanese epic war drama that is a reinterpretation of William Shakespeare’s play “King Lear.”

The film is set in feudal Japan and follows the story of Hidetora Ichimonji, a powerful and aging warlord who decides to divide his kingdom among his three sons. However, the decision sparks a series of betrayals, power struggles, and tragic consequences. As the kingdom descends into chaos and violence, Hidetora’s family is torn apart by greed, ambition, and the relentless cycle of revenge.

“Ran” is renowned for its breathtaking visuals, including its elaborate battle scenes and lush cinematography. Kurosawa’s meticulous attention to detail and his ability to capture the grandeur of the epic narrative are evident throughout the film. The use of color and symbolism adds depth to the story, and the film’s exploration of human nature, morality, and the consequences of power remains relevant and thought-provoking.

While the film is an adaptation of a Shakespearean tragedy, Kurosawa adds his unique cultural and historical perspective to the story, creating a distinctively Japanese interpretation. The performances, especially Tatsuya Nakadai’s portrayal of Hidetora, are powerful and contribute to the emotional impact of the film.

“Ran” is considered one of Akira Kurosawa’s masterpieces and a landmark in world cinema. It showcases his ability to blend traditional Japanese storytelling with universal themes and resonant characters. The film’s exploration of the destructive nature of unchecked ambition and the futility of violence has made it a timeless and compelling work of art.

Tokyo Story (1953)

“Tokyo Story” is a 1953 Japanese film directed by Yasujirō Ozu. It is widely regarded as one of the greatest achievements in world cinema and a masterpiece of Japanese cinema’s post-war era.

The film follows an elderly couple, Shukichi and Tomi, who travel to Tokyo to visit their grown-up children and grandchildren. However, they find that their busy children have little time for them, and they are often left alone or passed on to others. As the story unfolds, the film explores themes of generational conflict, societal changes, and the fleeting nature of human relationships.

Ozu’s unique filmmaking style is characterized by his use of static camera shots, low angles, and deliberate pacing. This approach gives the film a contemplative and meditative quality, allowing the audience to immerse themselves in the emotions and interactions of the characters. The film’s visual simplicity contrasts with the complex emotional landscape it portrays.

“Tokyo Story” delves into the universal theme of the generation gap and the evolving dynamics within families. It presents a poignant reflection on the changing social fabric of post-war Japan and the growing influence of modernization on traditional values. The performances of the cast, particularly Chishū Ryū and Chieko Higashiyama as the elderly couple, contribute to the film’s authenticity and emotional impact.

The film’s enduring resonance lies in its ability to evoke empathy and self-reflection in viewers from various cultural backgrounds. It prompts contemplation about the passage of time, the nature of familial bonds, and the complexities of life. “Tokyo Story” remains a timeless exploration of human relationships and a testament to the power of cinema to capture the profound in the ordinary.

Floating Weeds (1959)

“Floating Weeds” is a 1959 Japanese film directed by Yasujirō Ozu. It is a color remake of his 1934 silent film “Ukigusa monogatari” (also known as “A Story of Floating Weeds”). The 1959 film is often regarded as one of Ozu’s masterpieces and stands as one of his significant works before his death in 1963.

The plot of “Floating Weeds” centers around a group of itinerant theater actors who arrive in a small coastal Japanese town. The leader of the group is Komajuro, played by Ganjirō Nakamura, who also starred in the original silent film. Komajuro is a mature and charismatic man who is involved in a relationship with a young woman named Sumiko, played by Machiko Kyō. Sumiko is unaware that Komajuro is married and has an adult son.

The plot becomes more complex when Komajuro’s son, Kiyoshi, portrayed by Hiroshi Kawaguchi, arrives in town to study. Unaware of his father’s identity, Kiyoshi begins to suspect the relationship between Komajuro and Sumiko. This situation leads to a series of emotional and familial conflicts that highlight tensions between generations, the traditional and the modern, and the challenges of love and loyalty.

As typical of Yasujirō Ozu’s style, “Floating Weeds” is characterized by its contemplative direction and realistic portrayal of everyday life and human relationships. The film explores universal themes such as family, unrequited love, identity, and the struggle between tradition and social change. Ozu’s staging is marked by static shots, low angles, and a tranquil perspective that immerses the audience in the details of the characters’ lives.

“Floating Weeds” is widely appreciated for its deep sensitivity, visual elegance, and contemplative pace. It represents a significant moment in Yasujirō Ozu’s career and in Japanese cinema at large, capturing the transition from the era of silent cinema to the advent of color filmmaking. The film continues to be studied and revered by cinephiles and scholars as an extraordinary example of Ozu’s cinematic artistry.

Late Spring (1949)

“Late Spring” is a 1949 Japanese film directed by Yasujirō Ozu. It’s often regarded as one of Ozu’s most acclaimed and influential works, and it’s a prime example of his unique style and thematic concerns.

The film tells the story of a father-daughter relationship and explores themes of tradition, societal expectations, and the passing of time. The central characters are Noriko, played by Setsuko Hara, and her father, Professor Shukichi Somiya, portrayed by Chishū Ryū.

Noriko is a young woman who lives with her widowed father and takes care of him. However, her relatives and friends are concerned that she’s not yet married and try to arrange a marriage for her. Noriko is content with her life as it is and doesn’t want to leave her father. The film follows the emotional dynamics between Noriko and her father as well as the societal pressures they face.

One of the prominent themes of “Late Spring” is the tension between tradition and modernity. The film is set in post-World War II Japan, a time when societal norms were changing rapidly. The story presents the conflict between the traditional Japanese expectation of women to marry and fulfill their roles as wives and mothers, and Noriko’s desire to remain with her father and maintain their close relationship.

Ozu’s directorial style is characterized by his use of static camera shots, low angles, and a focus on the minutiae of daily life. This style allows for a contemplative and intimate exploration of his characters’ emotions and relationships. The film’s pacing is deliberate and measured, giving viewers ample time to reflect on the characters’ dilemmas and decisions.

“Late Spring” is often celebrated for its emotional depth, nuanced performances, and universal themes that resonate beyond cultural boundaries. It’s considered a classic of world cinema and a significant contribution to Japanese film history. The movie’s impact continues to be felt, and it remains a staple in discussions of Ozu’s work and the evolution of Japanese cinema.

Woman in the Dunes (1964)

“Woman in the Dunes” is a 1964 Japanese film directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara, based on a novel of the same name by Kōbō Abe. The film is renowned for its intense and surreal atmosphere, as well as its powerful metaphors and symbolism.

The plot of the film follows an entomologist named Junpei Niki (played by Eiji Okada), who finds himself trapped in a remote desert village with a woman named Keiko (played by Kyoko Kishida). Niki is searching for rare sand insects and ends up being invited by the locals to spend the night in a house located at the bottom of a large sand pit. The house is inhabited only by Keiko, who seems to have been abandoned by all other villagers.

However, Niki discovers that the intentions of the village are not exactly what they seem. It is revealed that his stay in the sand pit has been planned so that he helps the villagers dig sand and collect moisture for their domestic use. Niki is effectively imprisoned in the pit along with Keiko and forced to participate in this sand-collecting activity.

The film explores deep themes such as alienation, the struggle for survival, and human nature. The relationship between Niki and Keiko evolves over time, transitioning from a situation of conflict and opposition to a sort of forced coexistence and collaboration. Their struggle to survive and maintain their sanity becomes the core of the plot.

“Woman in the Dunes” is known for its extraordinary cinematography, which impressively captures the aridity of the desert and the isolation of the sand pit. The film also uses visual symbolism and allegorical themes to explore the human experience, the longing for freedom, and the conflict between the individual and society.

The film was acclaimed by critics and won several awards, including the Special Jury Prize at the 1964 Cannes Film Festival. “Woman in the Dunes” is considered a classic of Japanese art-house cinema and represents a profound reflection on the human essence through a surreal and engaging story.

Harakiri (1962)

“Harakiri” (also known as “Seppuku”) is a 1962 Japanese jidaigeki (period drama) film directed by Masaki Kobayashi. The film is renowned for its powerful storytelling, deep exploration of samurai ethics, and critical commentary on the feudal system in medieval Japan.

The film is set in the early 17th century, a period marked by civil unrest and political turmoil. It follows the story of Hanshiro Tsugumo, a ronin (masterless samurai), who arrives at the Iyi Clan’s residence and requests permission to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) in their courtyard. The leader of the clan is initially reluctant to grant his request, suspecting it might be a ruse to gain charity from the clan. However, Hanshiro is persistent and eventually begins to recount the tragic tale of another ronin, Motome Chijiiwa, who had come to the clan with a similar request.

As Hanshiro’s story unfolds in a series of flashbacks, the true purpose behind his visit becomes clear. He aims to expose the hypocrisy and cruelty of the samurai code and the feudal system that forces ronin into desperate acts. Through Motome’s story, it is revealed how the Iyi Clan exploited him, leading to his eventual death in a brutal manner. Hanshiro’s intention is to challenge the clan’s honor and integrity, shedding light on their moral decay.

“Harakiri” delves deeply into the conflict between personal ethics and societal expectations, as well as the clash between individual dignity and the rigid hierarchies of the samurai class. The film critiques the glorification of honor and the dehumanizing aspects of the samurai code. Its stark black-and-white cinematography and deliberate pacing contribute to the film’s solemn and contemplative atmosphere.

The film received critical acclaim upon its release and remains a classic of Japanese cinema. Its exploration of themes like honor, duty, and the harsh realities of the samurai era has made it a thought-provoking and enduring work. “Harakiri” is often considered a masterpiece that goes beyond mere entertainment to provide a profound examination of the human condition within a historical and cultural context.

Kwaidan (1964)

“Kwaidan” is a 1964 Japanese film directed by Masaki Kobayashi, renowned for being an anthology of horror stories based on Japanese folk traditions. The film offers a visually captivating and immersive experience that blends art cinema with horror genre elements.

The film consists of four distinct segments, each based on a story from the collection of supernatural tales “Kwaidan” written by Lafcadio Hearn. These stories are set in ancient Japan and are infused with supernatural elements, ghosts, and eerie atmospheres.

- “Black Hair” (“Kurokami”): This segment tells the story of a young samurai who leaves his wife to seek fortune in the city, but later realizes his mistakes and decides to return to her.

- “The Woman of the Snow” (“Yuki-onna”): This tale narrates the story of a man who is saved by a mysterious woman during a snowstorm. Years later, he encounters the same woman and discovers her true nature.

- “Hoichi the Earless” (“Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi”): This segment follows a young blind biwa player named Hoichi, whose captivating singing voice attracts the attention of vengeful spirits.

- “In a Cup of Tea” (“Chawan no naka”): The fourth story revolves around a samurai who, while drinking from a tea cup, discovers he can see the face of a mysterious man who appears to be from another world.

“Kwaidan” is celebrated for its artistic set designs, creative use of color, and the dreamlike atmosphere it creates. The film draws on the traditions of Noh and Kabuki theater to enhance the sense of mystery and suggestion. The soundtrack and sound effects contribute to crafting a spectral and eerie ambiance.

The film was well-received by critics and won the Special Jury Prize at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival. “Kwaidan” is considered an iconic example of Japanese art-house cinema and has influenced many other filmmakers and works in the horror and supernatural genres.

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003)

“Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring” is a 2003 South Korean film directed by Kim Ki-duk. This contemplative and visually stunning movie is known for its meditative exploration of life, nature, and human spirituality.

The film is divided into five segments, each set during a different season, which also correspond to different stages in a man’s life:

- Spring: The film begins with a young boy living with a Buddhist monk in a floating temple on a serene lake. The monk serves as his mentor, teaching him life’s lessons and the importance of compassion.

- Summer: As the boy grows older, he becomes a young adult. A troubled woman arrives at the temple seeking treatment for her illness. The young man’s struggles with his desires and emotions test his spiritual teachings.

- Fall: The young man leaves the temple and enters the outside world. He becomes involved in a crime that shatters his spiritual peace, leading him to seek solace back at the temple.

- Winter: The monk is now an elderly man, and he reflects on the cyclical nature of life and the passage of time. The young man, who has now repented for his past actions, takes on the responsibility of caring for the old monk.

- Spring (Rebirth): The cycle comes full circle as a new young boy arrives at the temple, echoing the film’s beginning. The themes of rebirth, forgiveness, and the continuity of life are emphasized as the story reaches its conclusion.

The film is known for its minimalist approach, with sparse dialogue and a focus on visual storytelling. The serene natural settings, particularly the floating temple on the lake, contribute to the film’s tranquil and reflective atmosphere. “Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring” explores themes of karma, impermanence, and the connection between humanity and nature.

The film received acclaim for its philosophical depth and artistic beauty. It was celebrated for its ability to convey profound ideas with a quiet and understated approach. “Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring” is often regarded as one of Kim Ki-duk’s finest works and has left a lasting impact on audiences interested in contemplative cinema.

Farewell My Concubine (1993)

“Farewell My Concubine” is a 1993 Chinese film directed by Chen Kaige. This epic drama is renowned for its sweeping storytelling, intricate character development, and exploration of the intertwining lives of two Peking opera performers against the backdrop of China’s tumultuous history.

The film follows the lives of two boys, Douzi and Shitou, who are brought up together in a Peking opera troupe in Beijing. Douzi, given the stage name Cheng Dieyi, specializes in playing female roles, while Shitou takes on male roles. Their friendship and collaboration are central to the film’s narrative.

The story is set against a backdrop of significant historical events in China, spanning from the 1920s to the 1970s. It follows the characters’ personal and professional struggles, their successes and failures, and how their lives are affected by China’s changing political landscape, including the Japanese occupation, the rise of the Communist Party, and the Cultural Revolution.

Cheng Dieyi’s love and devotion for his fellow performer, the “Concubine” of the title, lead to complex emotional dynamics between the characters. As the years pass and China undergoes various transformations, their friendship and artistic partnership are tested.

The film explores themes of identity, sacrifice, loyalty, and the enduring power of art. It also delves into the intersections between personal relationships and larger historical events. “Farewell My Concubine” is characterized by its sumptuous cinematography, elaborate period costumes, and the evocative use of Peking opera performances to enhance the narrative.

The film received widespread acclaim and won the Palme d’Or at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival. It was praised for its meticulous attention to historical detail, its powerful performances, and its exploration of complex emotions within the context of China’s social and political changes.

“Farewell My Concubine” is often regarded as one of the most important and influential films in Chinese cinema history. It offers a captivating and moving portrayal of personal relationships set against the backdrop of a nation’s evolving identity and historical events.

Raise the Red Lantern (1991)

“Raise the Red Lantern” is a 1991 Chinese film directed by Zhang Yimou. This visually sumptuous drama is known for its detailed portrayal of power dynamics and conflicts within polygamous Chinese households during the 1920s.

The film is set in 1920s China and follows the story of Songlian, a young woman played by Gong Li, who is forced to become the fourth wife of a wealthy master. Each wife lives in a separate house within the compound, and the master decides which wife will have the privilege of spending the night with him by lighting a red lantern outside her door.

The plot unfolds around the conflicts among the wives for the master’s favor and the competition to become the principal wife. As Songlian navigates the complexities of relationships within the household, she uncovers dark truths about power dynamics, injustice, and oppression that permeate the wives’ lives.

The film explores themes of female rivalry, control, tradition, and submission. Zhang Yimou’s direction highlights the contrast between the visual beauty of colors and traditional cultural elements and the darkness of emotions and hidden tensions within the walls of the household.

“Raise the Red Lantern” is renowned for its artistic direction, detailed cinematography, and accurate portrayal of customs and social norms of the time. The film received international acclaim and helped solidify Zhang Yimou’s reputation as one of the foremost directors in Chinese cinema.

The film also serves as a broader reflection on the status of women in traditional Chinese society and the complex power dynamics that govern family relationships. Gong Li’s performance in the role of Songlian was particularly acclaimed and contributed to establishing her career as one of the leading Chinese actresses.

Spring in a Small Town (1948)

“Spring in a Small Town” is a 1948 Chinese film directed by Fei Mu. This classic of Chinese cinema is celebrated for its nuanced portrayal of emotions, complex relationships, and its exploration of the impact of war on individual lives.

The film is set in a small town in post-World War II China and follows the story of a married woman named Yuwen (played by Wei Wei) who lives a quiet and routine life with her husband Liyan (played by Shi Yu). Their lives are disrupted when a former friend and admirer of Yuwen’s, Zhang (played by Li Wei), visits the town after an extended absence due to the war.

Zhang’s arrival triggers a series of emotional conflicts within the household. Yuwen’s feelings for Zhang are rekindled, and the film delves into the unspoken desires, tensions, and vulnerabilities of the characters. The film beautifully captures the subtleties of their interactions and the evolving dynamics between them.

“Spring in a Small Town” is known for its restrained and poetic storytelling. It explores themes of nostalgia, lost opportunities, and the desire for change. Despite its seemingly simple premise, the film delves deeply into the complexities of human emotions, using the subtleties of gesture and expression to convey the characters’ inner worlds.

The film is also recognized for its artistic cinematography, capturing the beauty of the town’s scenery and emphasizing the emotional atmosphere. While the film did not gain much attention upon its initial release due to the political climate of the time, it has since become revered as one of the most important works in Chinese cinema history.

“Spring in a Small Town” stands as a testament to the power of understated storytelling and its ability to convey profound emotions. Its themes and artistic approach have influenced generations of filmmakers, and it continues to be celebrated for its timeless exploration of the human experience.

Street Angel (1937)

“Street Angel” is a 1937 Chinese film directed by Yuan Muzhi. This classic film is recognized for its blend of romance, drama, and social commentary, and it is often regarded as one of the highlights of the “Golden Age” of Chinese cinema in the 1930s.

The film is set in the slums of 1930s Shanghai and follows the story of a young woman named Xiao Hong (played by Zhou Xuan) who becomes a street singer after her family faces financial difficulties. She forms a close bond with a painter named Xiao Chen (played by Zhao Dan), and their relationship becomes a central focus of the film.

As Xiao Hong and Xiao Chen navigate the challenges of their lives in the impoverished urban environment, the film delves into issues such as poverty, social inequality, and the struggles of the working class. The story unfolds against the backdrop of a society undergoing significant changes and highlights the tensions between personal dreams and the harsh realities of life.

“Street Angel” is noted for its melodramatic storytelling and its portrayal of characters striving for a better life against the odds. It is also famous for Zhou Xuan’s poignant performance and her rendition of the song “The Wandering Songstress,” which became an enduring classic in Chinese music.

The film’s cinematography and art direction capture the atmospheric urban landscapes of 1930s Shanghai, adding to the film’s visual appeal. “Street Angel” was well-received upon its release and contributed to the popularity of both its stars, Zhou Xuan and Zhao Dan.

Despite the passing of time, “Street Angel” remains an important work in Chinese cinema history and serves as a window into the social issues and artistic trends of its era. It stands as a testament to the enduring power of classic films to resonate with audiences across generations.

Song at Midnight (1937)

“Song at Midnight” (also known as “Ye ban ge sheng”) is a 1937 Chinese film directed by Ma-Xu Weibang. This film is considered one of the earliest examples of Chinese horror cinema and had a significant impact on the country’s film industry.

The movie is a Chinese adaptation of Gaston Leroux’s novel “The Phantom of the Opera” and is set in a dilapidated theater. The story follows the tragic fate of a deformed musician named Lingyu, who, after being betrayed and dishonored, becomes a haunting phantom within the theater.

The plot unfolds with elements of mystery, tragedy, and the supernatural. Lingyu returns to the theater to seek revenge and protect the opera’s heroine, sung by a young actress, from the greed and evil plots of other characters.

“Song at Midnight” is known for introducing the horror genre to Chinese cinema and influencing many subsequent films. The movie blends the supernatural with dramatic and musical elements, characterized by its eerie atmospheres and portrayal of dark themes. The performance of the protagonist by Jin Shan was particularly acclaimed.

The film is considered a cult classic and has left a lasting imprint on Chinese film culture. It has inspired numerous reinterpretations and adaptations over the years, demonstrating its relevance and influence in the Chinese and international film landscape.

The Spring River Flows East (1947)

“The Spring River Flows East” (also known as “Tianyunshan chuanqi”) is a two-part Chinese film released in 1947, directed by Cai Chusheng and Zheng Junli. This epic melodrama is considered a classic of Chinese cinema and is renowned for its sweeping narrative, emotional depth, and depiction of the turbulent times in China during the late 1930s and early 1940s.

The film is set against the backdrop of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War. It follows the life of a young woman named Sufen (played by Bai Yang), who comes from a poor rural background. She marries a young officer named Zhang Zhongliang (played by Shangguan Yunzhu), but their marriage faces challenges due to the upheavals of war and political changes.

“The Spring River Flows East” is notable for its portrayal of personal struggles against the backdrop of historical events. The film captures the emotional toll of war, the hardships faced by ordinary people, and the societal changes brought about by the conflicts. It explores themes of love, sacrifice, separation, and the indomitable human spirit in the face of adversity.

The film’s two parts, “Eight War-Torn Years” and “Sowing the Seeds,” cover different periods of history and showcase the characters’ journeys through various hardships and life changes. The storylines are interwoven with broader historical events, providing a sense of the societal context in which the characters’ lives unfold.

“The Spring River Flows East” is considered a milestone in Chinese cinema history and is often lauded for its emotional depth, strong performances, and its ability to convey the human impact of historical events. It continues to be celebrated as one of the most important and enduring works of Chinese cinema, showcasing the power of film to reflect the complexity of individual lives within the larger canvas of history.

The Goddess (1934)

“The Goddess” is a 1934 Chinese film directed by Wu Yonggang. It is considered one of the earliest and most influential works of Chinese cinema, known for its powerful storytelling and its exploration of social issues and the plight of women in society.